Drawing in the 1990s: historical revisions and phantom visions

by Karen Kurczynski • June 2023. In collaboration with Drawing Room, London • Journal article

Introduction

In The Minotaur Hunt FIG. 1, Nicole Eisenman (b.1965) created a larger-than-life scene of nude, female-presenting figures on horseback hunting minotaurs. Measuring nearly 5 metres long, it resembles a mural-scale draft or cartone (cartoon), in which feminine and androgynous protagonists occupy a space typically reserved for male heroes. Regarding making the work, Eisenman recalls that ‘the wall […] behaved exactly like a piece of gessoed paper. […] I just wanted to make giant drawings just like works on paper’.1 Although Eisenman had previously tried making murals on canvas, this was one of a series of works from the 1990s that used drawing to turn a monumental image into a critique of monumentality itself, with its patriarchal lineage and authoritative presence. Around the time these works were produced, Eisenman noted that the historical distinctions between painting and drawing were dissolving, while at the same time drawing’s delicacy and ephemerality and its history as a marginal medium remained defining aspects of its critical potential:

I don’t understand the big distinction made between drawing and painting. If it’s ink on the wall it’s called a wall drawing, but if it’s ink on gessoed canvas it’s a painting. It doesn’t make sense when I compare a little dinky painting with some of the 60-foot drawings I worked so hard on! Maybe the delicacy is the difference. Maybe the history of the two mediums explains it.2

Indeed, the subversive associations of drawing’s relationship to fragility make possible a link between its radically inclusive aesthetics and a global feminist politics of solidarity across differences.

The difficulty of defining drawing is the very quality that makes it a key medium in the revelation of historical violence and the visualisation of alternative futures. In a 2011 article titled ‘Drawing is the new painting’, the present author wrote that, in contrast to painting, drawing resists finish – even as the point of the article, with its ironic title, was to acknowledge the impossibility of separating drawing from contemporary painting.3 Drawing is elusive and resists definitions; its emphasis on process also makes it resistant to exposure and the aesthetic of spectacle. Although, as Eisenman demonstrates, it can easily be magnified to the monumental scale of history painting, while simultaneously subverting the genre through its rejection of the standard rhetoric of permanent dominance. Drawing’s associations with process also make more room for observers to enter into dialogue with the work of art and identify their own agency within it. This recalls Michael Rothberg’s description of art’s potential to cultivate an ‘implicated subject’ instead of a passive spectator, including the responsibility of privilege, or what it means to have survived or indirectly benefited from political violence.4 Thus, drawing in particular engages viewers to recognise their own positionality in relation to past and present injustices.

Drawing also resists commodification through its alignment with economic and material accessibility. Still, these characteristics do not represent any inherent qualities – they can only remain mere tendencies and associations that give drawing a critical edge only by contrast to some other more ‘finished’ format. It could be argued that the definition of drawing is dialectical to a more profound degree than other artistic mediums: it can be made of paint but resist definition as a painting, it may exist as an action, a trace of bodily movement or it may exist in print. Nonetheless, drawing can also be understood to have a particular allyship with ‘outsider’ viewpoints, which have been central to the tenets of the avant-garde since its inception in the nineteenth century. As Caroline Levine writes, the representation of subversive ideologies has been a foundational element of the social role of art in modern culture:

If the avant-garde is defined as that aspect of the cultural field that deliberately challenges dominant assumptions and values, then its social function is to act as a permanent minority. In its deliberate repudiation of national traditions and majority tastes, the artwork refuses assimilation and consensus and so resists integration into a unified nationalist politics. I am arguing, in other words, that there is a close structural kinship between minority groups – racial, ethnic, religious, or political – and avant-garde experimentation, and that the avant-garde is routinely associated with unsettling outsiders in the rhetoric of those who urge a strongly united ‘people’.5

Although the term ‘avant-garde’ has arguably lost its incisiveness, and the notion of ‘minority groups’ is problematic – for example, the majority of peoples in the world are people of colour – the ideas signified by these terms as imperfect placeholders persist. Such inadequate but necessary descriptors parallel the ways that drawing is and has been framed: as preliminary, secondary and the embodiment of sheer potential in relation to painting, which still remains a metonym for contemporary art as a whole. Drawing has functioned as a way to assert the spontaneous or critical gesture since the avant-garde Realist and Impressionist experiments of the nineteenth century. Separated from painting only by an infrathin – a highly subjective, notably questionable and possibly only phantom margin – drawing signifies the possibility of other ways of existing.6

The experience of the outsider is often fraught with vulnerability, a state that the medium of drawing shares. This is perhaps most easily recognised in one of its most common supports: paper. This recalls Judith Butler’s theory of vulnerability as a radical exposure of political power and a necessary part of resistance to authority. Butler notes that:

Vulnerability traverses and conditions social relations, and without that insight we stand little chance of realising the sort of substantive equality that is desired. Vulnerability ought not to be identified exclusively with passivity; it makes sense only in light of an embodied set of social relations, including practices of resistance.7

Vulnerability manifests in situations when people are subjected to power. Drawing not only signifies this quality in works that dramatise their own fragile materiality, but can also endow its provisional images with the power of potential transformation.

This article pinpoints its focus by utilising contemporary feminist approaches to ‘coalition through difference’.8 Scholarship by Griselda Pollock, Catherine de Zegher, Marsha Meshkimmon and Paul Sawdon suggests important connections between the medium of drawing and feminine identifications.9 Without resorting to reductive notions of a ‘female sensibility’, Meshkimmon and Sawdon trace the ‘significant overlaps’ between drawing and women and feminist artists.10The artists discussed in this article, including Eisenman, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b.1940), Kiki Smith (b.1954) and Britta Marakatt-Labba (b.1951), produce work that engages with historical imagery, the ongoing impact of colonialism, the politics of access to education and culture, and processes of gendered and racial identification shaped by historical and political developments. These critical possibilities relate intimately with their respective, radically heterogeneous practices of drawing. The expansive possibilities of drawing allowed these artists to envision and embody adamantly subjective, defiant and decolonial visions of community.

Visions and hauntings

In The Minotaur Hunt, Eisenman proposes a romantic wish, an erotic utopia and a parodic image of violence; the work does not embody a future so much as a phantom vision to counter the possibilities imposed by patriarchal and heteronormative Western culture. This vision haunts us from a contemporary past: the 1990s. It emerged as a foil to romantic, second-wave, white and heterosexual feminist ideas of feminine community. In its place came a radically pluralistic, politicised, punk-inflected third wave, characterised by queer, decolonial, postcolonial and multiracial perspectives.

The political potential of the visionary in decolonial practice links both to feminist activist approaches and descriptions of drawing. All three approaches foreground the political significance of fantastic visions of alternative futures and haunted visions that register past violence. The Mississauga Nishnaabeg writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson emphasises the importance of the visionary to make a ‘resurgence’ of Indigenous cultures possible: ‘dreams and visions provide glimpses of decolonized spaces and transformed realities that we have collectively yet to imagine’.11 Similarly, Butler insists in their examination of women and transgender rights that:

Fantasy is part of the articulation of the possible; it moves us beyond what is merely actual and present into a realm of possibility, the not yet actualized or the not yet actualizable […] The critical promise of fantasy […] is to challenge the contingent limits of what will and will not be called reality […] It points elsewhere, and when it is embodied, it brings the elsewhere home.12

The role of drawing as a conduit for fantasy has been foundational to both practices and theories of the medium. Jacques Derrida notes in Memoirs of the Blind that drawing ‘escapes the field of vision’ because the moment that the pen touches the paper, the artist turns to the invisible in a perpetually frustrated attempt to capture the visible. Therefore, he argues, ‘this heterogeneity of the invisible to the visible can haunt the visible as its very possibility’.13 Although the poststructuralist account risks divorcing the process of drawing from political agency, it is this prying open of the gap between observed or imagined image and artistic manifestation that allows a revisionist politics to take form – precisely through the haunting that drawing makes palpable. In Derridean terms, drawing can capture a haunting of the existing world by other possibilities yet to come.

The visionary drawings discussed in this article specifically manifest responses to social and political injustices. Avery Gordon writes that ‘haunting is one way in which abusive systems of power make themselves known and their impacts felt in everyday life, especially when they are supposedly over and done with (slavery, for instance) or when their oppressive nature is denied (as in free labor or national security)’.14 For Gordon, haunting registers ‘modernity’s violence and wounds’ precisely by calling attention to ‘the broader issues of invisibility, marginality, and exclusion’ embodied not in the quantitative reasoning of sociology, but the affective and qualitative accounts of literary and artistic texts.15 Since Gordon’s groundbreaking analysis in 1997, the Black Studies scholars Christina Sharpe and Saidiya Hartman have extended its insights in their influential studies of living ‘in the wake’ of slavery. Sharpe seeks to critically account for ‘what this imagining […] calls on “us” to do, think, feel in the wake of slavery – which is to say in an ongoing present of subjection and resistance; which is to say wake work’.16

This labour allows contemporary observers or readers to reimagine the lost lives and dreams of figures like the enslaved woman Venus, discovered in the archive of history and reanimated by Hartman. She describes the ‘inevitable return’ of Venus as both ‘“haint”, that is, one who haunts the present, and as disposable life’.17 Such reanimated visions or phantasies, which Hartman terms ‘critical fabulations’, enable us to work through histories of violence without losing sight of its specific material impacts on people who lived in the past and those alive today. Drawing’s manifestation as a specific bodily trace combined with its resistance to finish, permanence and monumentality are what endows the artistic imaginings of an alternative past or a liberated future with qualities of the visionary or the haunted.

A major minor medium

In the 1990s drawing came into new prominence, which can be understood in direct correlation to an increasing visibility of contested artistic strategies and historically marginalised discourses. In 1989 The Other Story opened at the Hayward Gallery, London, featuring the work of Asian, African and Caribbean artists in post-war Britain; the following year The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s opened at the New Museum, New York, bringing together Hispanic, Asian, African American, Indigenous and European artists to address identity issues of the 1980s; and the 1993 Whitney Biennial was the most diverse exhibition at any American institution to date.18 These and other critical reassessments of the histories of race and colonialism spurred intense debates over neoliberal definitions of multiculturalism, even if it meant that complex strategies were reduced to one-dimensional iterations of ‘identity politics’.

Moreover, in the wake of the AIDS crisis, an economic recession following the 1989 financial crash and cuts to government funding for the arts in the United States, there was a move towards the presentation of oppositional practices.19 At the same time, the collapse of the Soviet Union opened up a new era of globalisation shaped by neoliberalism and capitalism. By the new millennium, postcolonial approaches by such theorists as Homi K. Bhabha had provided the dominant descriptions of cultural responses to globalisation.20 Subsequently, decolonial approaches from Latin American and Indigenous art histories began to revise and repoliticise what had become the academic language of postcolonialism.21

The curator Laura Hoptman wrote in 2008 that ‘the 1990s ushered in an efflorescence of contemporary drawing not seen since the heyday of Postminimalism’.22 Drawing practices of the 1960s and 1970s that made drawing ‘a major and independent medium with distinctive expressive possibilities altogether its own’ were taken up once again toward the turn of the millennium.23 Drawing in the 1960s presented a direct critique of the ‘commodity status and market orientation’ of the art world.24 Assertions that ‘drawing is a verb’ emphasised process and experimentation over the finished drawings that for centuries had already counted as a ‘noun’ – in other words, as art.25 In the 1990s artists once again emphasised drawing’s historical iterations as preliminary sketch or conceptual design; its affiliation with line as a medium of imaginary potential and movement; its identification with writing and poetry; its tendency to rely on paper as an ephemeral and symbolically vulnerable support; and its function as a connector or translator among multiple media. These aspects have been foregrounded in recent accounts by de Zegher and Cornelia H. Butler that investigate drawing’s oppositional, feminist and performative potential.26

Histories of drawing, such as Bernice Rose’s essay in the catalogue for her 1976 exhibition Drawing Now: 1955–1975, have addressed the formal breakthroughs and critical messages of the 1960s but failed to take account of their cultural exclusions. Recent scholarship addresses the gender discrepancies that limited discussions of those breakthroughs to major male artists, but most accounts still fail to address the role of whiteness and privilege in establishing the canonical case studies of drawing.27 More inclusive discussions of the past few decades of Latin American, Asian, Indigenous and African American artists who employ drawing complicate this narrative, but remain specialised accounts or case studies in a larger history of contemporary drawing.28 Rose’s 1992 follow-up to Drawing Now: 1955–1975, titled Allegories of Modernism: Contemporary Drawing, marked the shift from the celebration of monumental painting and the rise of the art market in the 1980s to a new self-consciousness about representation and the performative body in the early 1990s, but without contesting the assumed whiteness and heteronormative masculinity of the body in question.29 A year later the 1993 Whitney Biennial included a majority of women and artists of colour for the first time in the Biennial’s history, marking a moment of widespread recognition for a whole host of formerly marginalised, feminist and queer artistic perspectives, and included key drawings alongside mostly installation and new media works.30

The artists discussed in this article crossed the experimental and anti-capitalist experiments of the 1960s with the emphatically subjective politics of punk, lesbian, feminist and Indigenous rights movements of the 1980s and 1990s. Their work further expanded drawing’s possibilities for connection, oppositional expression and critique of dominant histories and social identifications. Rather than focus on artists who have already received extensive recognition for expanding the possibilities of drawing in this period, such as Raymond Pettibon (b.1957) or William Kentridge (b.1955), this account centres perspectives previously overlooked in accounts of the 1990s.31

Ephemeral murals and feminist antagonisms

Eisenman’s Minotaur Hunt was one of a series of ephemeral installations that the artist created as a complement to their queer activist projects, such as the group exhibition they co-curated with the artist Chris Martin at Franklin Furnace, New York, in 1992, The Lesbian Museum: 10,000 Years of Penis Envy. The work dramatically recentres feminist and queer perspectives that mainstream culture has pushed to the margins. It makes a temporary, phantasmatic proposal of a radical utopia, in which female-presenting figures aggressively attack an anachronistic symbol of modern monstrosity: not just any minotaur, but the minotaur of Picasso.

A central, voluptuous, long-haired figure spears a writhing minotaur in the foreground with help from a figure on foot. Two women at the far left embrace and pose for a picture, while a minotaur, with distinctly white skin, writhes at their feet. The mural presents a complex and ambivalent combination of homage to a series of great Western artists whom Eisenman admired and a queer feminist critique of the exclusivity and commodification of their paintings. Eisenman’s work makes highly visible the strength, aggression, power and eroticism of feminine, transgender and non-binary subjects, who have been rendered historically invisible by the overwhelming predominance of masculine imagery in Western painting.

The scene becomes even more complex when one considers the racial identifications that have since come to frame the European heritage of art history. The embodiment of aggression in these nudes – led by a light-skinned figure on horseback with a darker-skinned henchwoman and enacted against two notably whiter minotaur figures – reads simultaneously as a revenge taken against white masculine icons of physical power and a disturbing attack on two monstrous outsiders by a multiracial and multigendered coalition. The racial implications of Eisenman’s work have been overshadowed by its critique of gender and sexuality, but its equivocal and humorous redrawing of figures of authority in a carnivalesque scene of gleeful destruction metaphorically tramples any standard of racial or gender superiority by breaking down multiple binary formulas at once.

Eisenman’s juxtaposition of feminist rage, lesbian separatism and ridicule of white dominance emerged at a key moment in the development of feminism. In the 1990s third-wave feminism materialised as a more populist, culturally diverse and queer-positive movement. Reflecting on feminist theory at the end of the 1980s, Teresa de Lauretis observed that ‘this understanding of a diversified field of power relations occurred or was brought home, as it were, when the writings of women of color, Jewish women, and lesbians constituted themselves as a feminist critique of feminism’.32 Progressive feminism also took seriously its dialogue with women of colour critiques and queer theory, just as more recently it has developed a solidarity with transgender perspectives.33 As de Lauretis summarises:

the feminist subject, which was initially defined purely by its status as colonized subject or victim of oppression, becomes redefined as much less pure – and not unified or simply divided between positions of masculinity and femininity, but multiply organized across positionalities along several axes and across mutually contradictory discourses and practices.34

The Minotaur Hunt was a site-specific drawing for Trial Balloon, New York, a non-commercial space run by the artists Nicola Tyson (b.1960) and Angela Lyras, which was dedicated to artistic experimentation for an emerging lesbian subculture in the early 1990s. A monumental riposte to the absence of lesbian imagery in historical visual culture, it was read at the time as a simplistic reversal of androcentric art-historical imagery: ‘less the product of art-historical critique than the appropriations of a fan’.35 Today, as Eisenman’s work acquires a new level of global artistic acclaim, critics are finally re-evaluating the early dismissals of their work.36 Early works such as The Minotaur Hunt are now being assessed as a profound engagement with historical imagery from a critically subjective position.

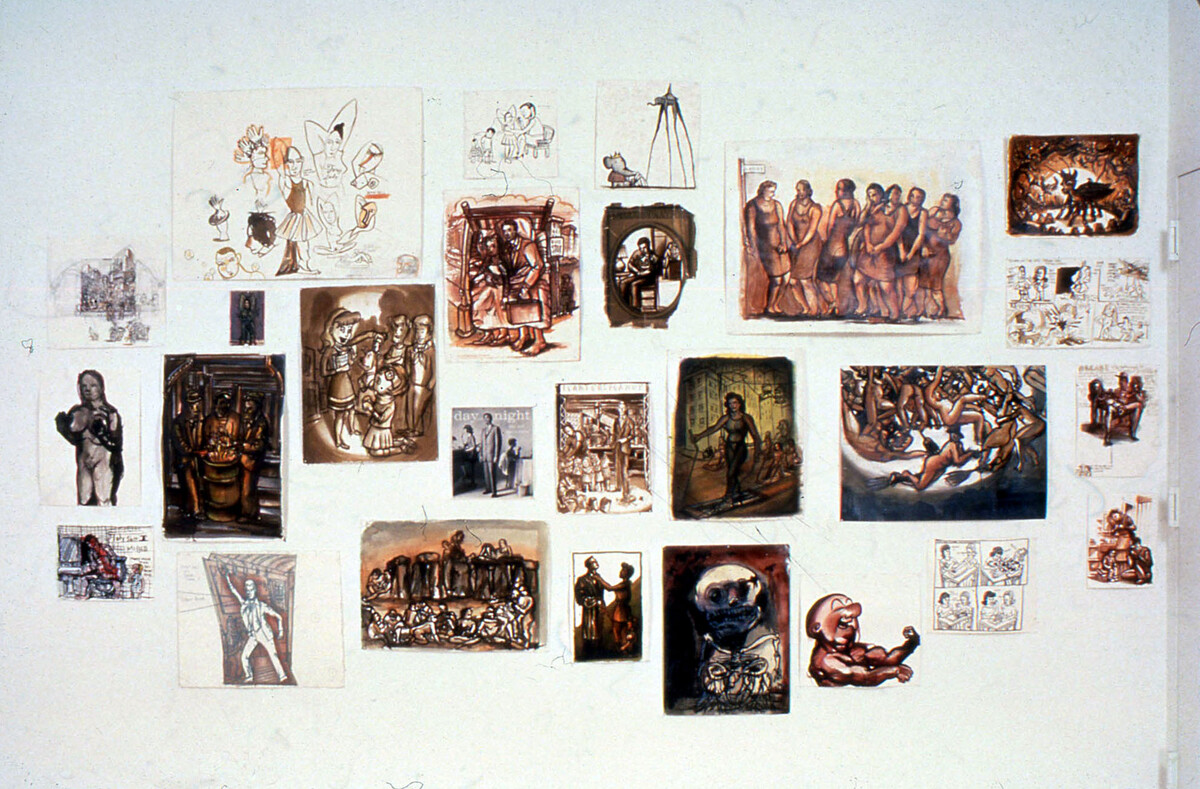

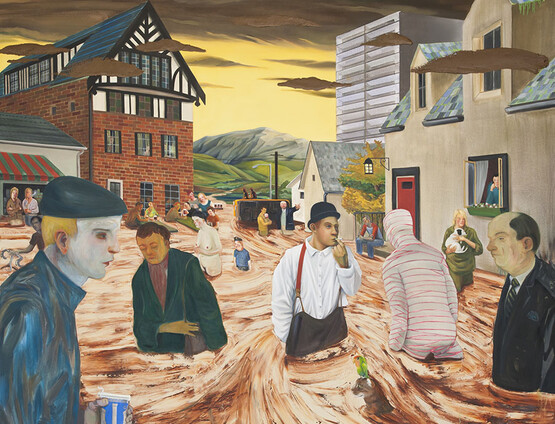

Eisenman’s murals were complementary to the artist’s installations FIG. 2, which are made up of collections of smaller drawings marked by radical juxtapositions of sexual imagery, political statements, strange reveries, trashy humour and appropriated consumer products. Adopting drawing styles associated with sketching, doodling and diary-keeping allows Eisenman to produce works that resemble outsider commentaries on mainstream culture. As the artist Amy Sillman (b.1955) has observed, ‘drawing is a lens, a process, through which Eisenman projects her raw emotional material. In the form of ink on paper, feeling becomes form in situations of humour or shame. We find her characters enacting narratives, anecdotes, predicaments of sex, longing, melancholy or embarrassment’.37 The accumulation of smaller heterogeneous musings is essential to Eisenman’s contemporary interventions that afford drawing the status historically applied to painting. They achieve monumentality not only by parodying history painting, but also through the aggregation of minor narratives in an emphatically playful and erotic tone. The oppositional, desiring and cantankerous gaze that plays out in Eisenman’s early work takes an adamantly subjective, feminist and queer stance against monumental images of beauty, distinction and political triumph.

Activism and revisionist histories

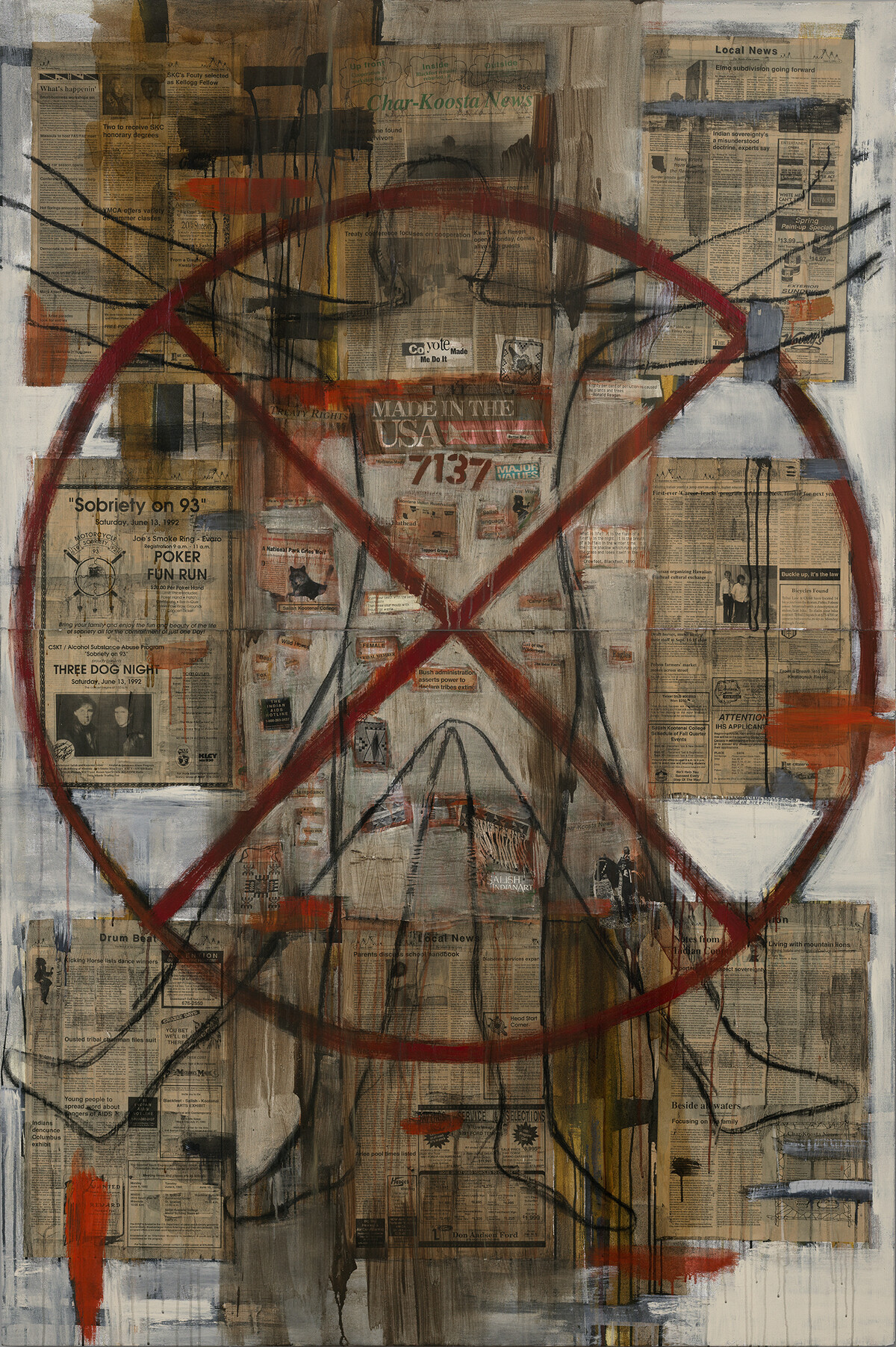

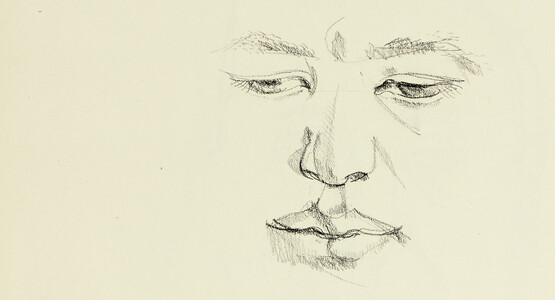

In The Red Mean FIG. 3, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith drew two life-sized outlines of her body in charcoal and overlaid them with a drawing in red paint of a medicine wheel. Smith’s form is drawn on layers of newsprint and ephemera, which attest to the day-to-day experience of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, of which she is a member. The work references an interaction with her art professor at Framingham State College twenty years earlier. When looking at Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man (c.1490; Gallerie dell’Accademia, Venice), Smith asked the professor about the ideal proportions of the female body; he responded that there were no feminine equivalents.38 In response to this erasure of her bodily specificity, she draws her own presence as an erasure – one that is doubly negated by the large red ‘X’ overlaid on it. This form references the medicine wheel, which was originally a Plains Indian symbol of harmony and interconnectedness and is now referenced by Indigenous communities across North America. Smith situates the ‘X’ over the reproductive centre of her body. The boldness of the thick red lines counter the vulnerability implied by the sketchier boundaries of her form, which recall the chalk outline of a murder victim.

Smith’s drawn outlines are at once phantoms of colonial violence and Native American lifeways. They are in dialogue with new approaches to Native ‘resurgence’, a practice of rebuilding Indigenous knowledge and practices of contemporary living. The Red Mean is one of a series of ‘Red’ works completed by the artist, many with titles that feature the phrase ‘I See Red’, which connect the violent implications of the colour red with the outmoded racial term that emerged as a counterpoint to foundational descriptions of whiteness and Blackness under slavery.39 The Red Mean centres Smith’s female and Indigenous body while pointing to its absence from American history. The number ‘7137’ at the centre is her official Native identifier, a number given to anyone born on a federally recognised reservation. Directly above is a bumper sticker that reads ‘MADE IN THE USA’, a reference to the absurdity of the United States government’s ‘authority’ to decide who is a member of what Native peoples consider autonomous sovereign nations.

Smith produced the ‘Red’ works during the celebrations for, and protests against, the Columbus Quincentenary, which marked five hundred years since Christopher Columbus’s 1492 invasion of the Americas – an originating moment for the hegemonic discourses of modernity, race and colonialism.40 Pages from the 5th June 1992 edition of Char-Koosta News form the background of The Read Mean, including such headlines as ‘Indians denounce Columbus exhibit’ and ‘Indian sovereignty’s a misunderstood doctrine’. Although the work is multimedia, drawing plays a key role in connecting the imagery together and making its statement graphically.

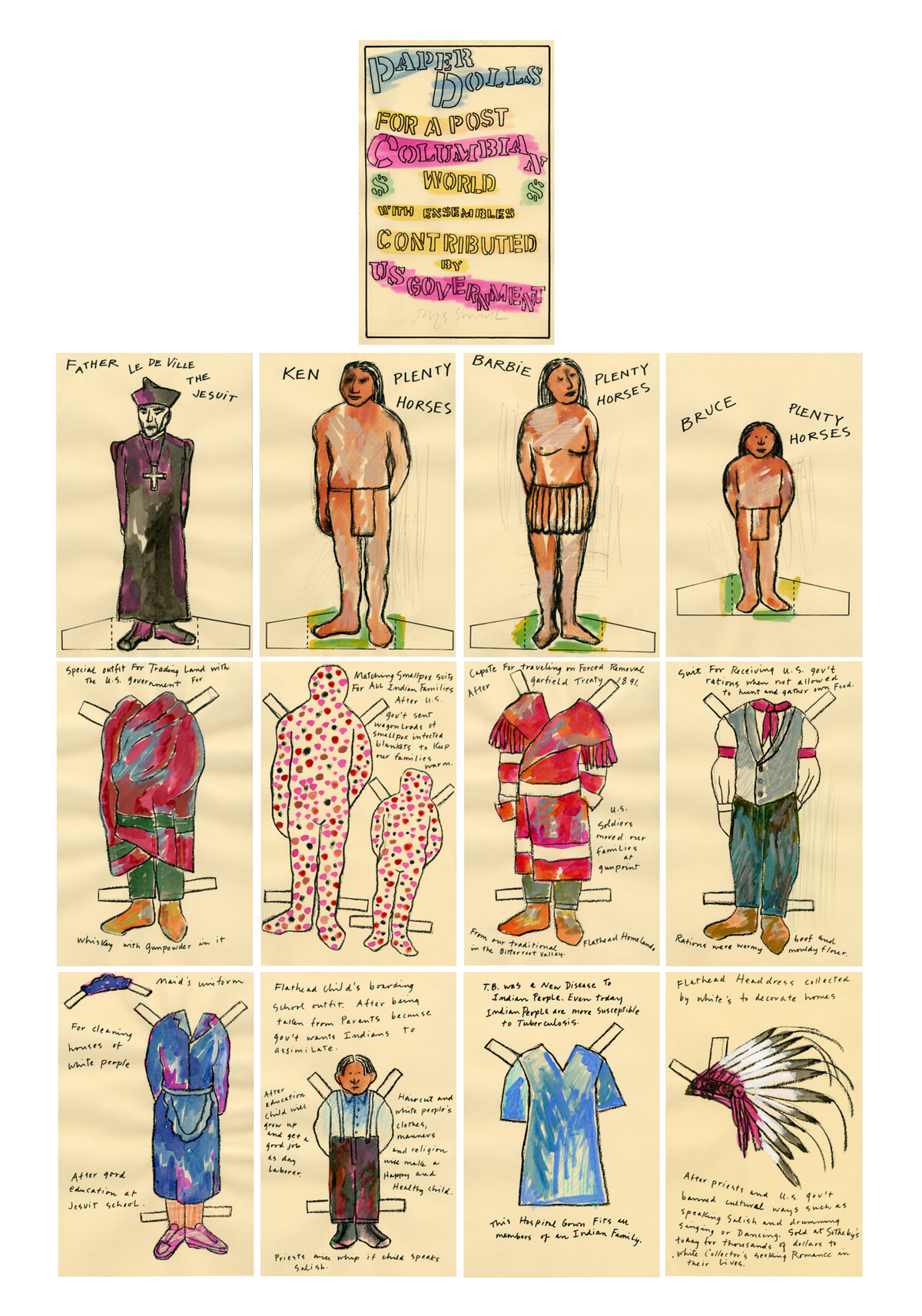

Just as she embarked on the monumental ‘Red’ works, Smith also produced a series of thirteen drawings titled Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government FIG. 4. Smith copied these drawings on a Xerox machine so that they could be cheaply and efficiently hand-coloured and mailed out for inclusion in multiple group exhibitions around the United States and Germany. The format juxtaposes the paper doll toys for girls popularised in the nineteenth century with references to more recent consumer culture, as evidenced by the names she gives to her characters: Barbie and Ken Plenty Horses (a common Salish Kootenai family name) and their son, Bruce, as well as the Jesuit priest Father De Ville. The family’s paper outfits include a government boarding school uniform, a cleaning woman’s uniform and a ‘special outfit for trading land with the U.S. government for whiskey with gunpowder in it’. They also include, in vivid polka-dotted shapes, ‘matching smallpox suits for all Indian families after US gov’t sent wagon loads of smallpox infected blankets to keep our families warm’.

Smith’s dolls reference the French and American colonisation and displacement of the Salish people of Montana in the 1890s, but also function as a global allegory for many Indigenous experiences. Subverting a history of children ‘playing Indian’ in the United States, Smith ‘reappropriates the appropriators, using the dolls to relay a dark story dripping in sarcasm’.41 With their splashes of bright pink and reference to ‘feminine’ toys, the drawings insert themselves into the traditionally masculine genre of historical representation, while commenting on the social vulnerability of Indigenous people subjected to colonisation. The hand-written labels form a key part of the message, framing these desk-sized images as timely and spontaneous riffs on a history of colonisation intimately experienced by the artist, now multiplied and injected back into visual culture as a decolonial communiqué.

Smith’s dolls use humour as a tactic to expose the violence inflicted on Native families under colonialism. Moreover, the reference to ephemeral toys erodes the power of histories that haunt the present. Eisenman’s work, on the other hand, examines the vulnerability of the desiring queer subject. Their drawing installations reframe the art-historical gaze from a lesbian viewpoint. Both artists critique the gendered and racial coding of art history by insisting on the class and cultural specificity of the jokes and narratives that shape their characters. The celebration of the partial, the unfinished and the connection of the personal to the political emphasised in these drawings proclaims the monumental importance of embodied feminine and queer perspectives in a formerly ‘minor’ medium that resists a single definitive interpretation.

The subversion of canonical heteronormative and patriarchal imagery in such works claims a monumental space for the recognition of an intersectional ‘multiple consciousness’, to paraphrase the terminology of W.E.B. Du Bois.42 This is not to say that the artists in some simplistic way ‘represent’ their evolving identities or experiences, but rather that their works make visible complex processes of identification. They share a focus on drawing to develop visionary images that speak eloquently to the relationship between social identity, history, power and vulnerability. Their works explicitly attack the imposed codes of identity in ways that unravel the threads that tie them together.

Decentring whiteness

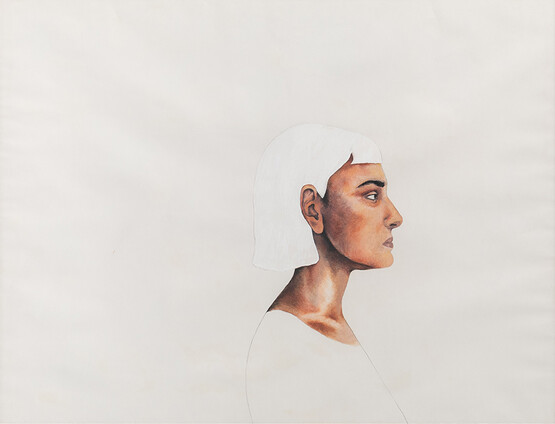

Drawing is uniquely able to connect private explorations of identification to pre-established paradigms of history and identity. In so doing, it illuminates the ways that everyday life is shaped by the social power that adheres to specific identifications. At the same time, the playfulness and unpredictability of drawing facilitates new identifications and a symbolic liberation from limited public discourses. For example, drawings by Kiki Smith (b.1954) of herself as an older woman holding her deceased cat in the pose of a pietà FIG. 5 foreground the unique ability of drawing to emphasise vulnerability and destabilise hegemonic definitions of both feminine beauty and whiteness. Pietá was made through a complex process of drawing on lithographic plates and adding handmade marks to the assembled prints.43 The support – multiple sheets of crinkled Nepalese paper – is much stronger and heartier than it appears, while conveying an unmistakable appearance of something frail and wizened. Smith, who was about forty years old when she made this body of work, transforms herself into the often culturally invisible image of the older white woman. She humorously embodies the trope of the cat lady, while dramatising a profound connection with a non-human species. She also reframes a religious iconography that is fundamental to the patriarchal and Eurocentric discourse of both art history and Christianity. According to the academic Richard Dyer, the Christian image of the Virgin is a central archetype of white femininity, defined by its attributes of purity, compassion and transcendence of the material body.44 Smith gives material specificity to the image, emphasises its impurity and expands its definition of compassion to encompass the non-human world.

One can compare Kiki Smith’s self-portraits to the way that Jaune Quick-to-See Smith situates herself in the location of the canonical Vitruvian Man, a kind of ‘golden mean’ of human proportion that proposes the idealised Euro–American male body as the archetype of all human imagery. Both artists redraw the defining imagery of white supremacy to claim their own places and recognise histories of violent exclusion. Their images are mythic but at the same time tentative, ephemeral and specific: Kiki Smith reduces whiteness to a singular and vulnerable person whose identity develops through an interspecies relationship, whereas Jaune Quick-to-See Smith proclaims the visual sovereignty of a feminine body linked inextricably to her contemporary Native nation.

In northern Scandinavia, the Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba produces a comparable claim for cultural sovereignty and resurgence through her critical use of traditional feminine and Indigenous media. Her embroidered works of art reject the typical elegiac representations of the ‘vanishing North’. Like Jaune Quick-to-See-Smith, Marakatt-Labba also began her career as part of a politico-aesthetic movement in the 1970s that pushed open the insider boundaries of contemporary art. Whereas Smith organised the Grey Canyon Group of contemporary Native artists in New Mexico as part of the Pan-Indian Movement, Marakatt-Labba joined the Sámi Artists Group in Máze, Norway, from 1979 to 1983, where she participated in the Alta-Kautokeino political protests against government plans to displace local communities and divert their water supply for hydroelectric power. The Norwegian art historian Hanna Horsberg Hansen aptly identifies the Máze movement as an avant-garde formation and describes the Sámi Artist’s Group activities as an Indigenous nation building project.45 The group established a groundbreaking artistic centre in Sápmi, the transnational Sámi homeland in northern Scandinavia and Russia; the group represented the first movement specifically for contemporary Sámi art. Notably, the group inserted itself directly into an international pan-Indigenous dialogue by joining the Nordic Council as opposed to any national artist unions, and sent delegates to the first global Indigenous meetings in Canada in the 1970s. These moves helped advance contemporary Indigenous art towards equity in the art world, to the point that today, as the Sámi scholar Harald Gaski argues, ‘the Indigenous voice has developed from simply claiming its own space to actually making itself heard on the same terms as all the other voices’.46

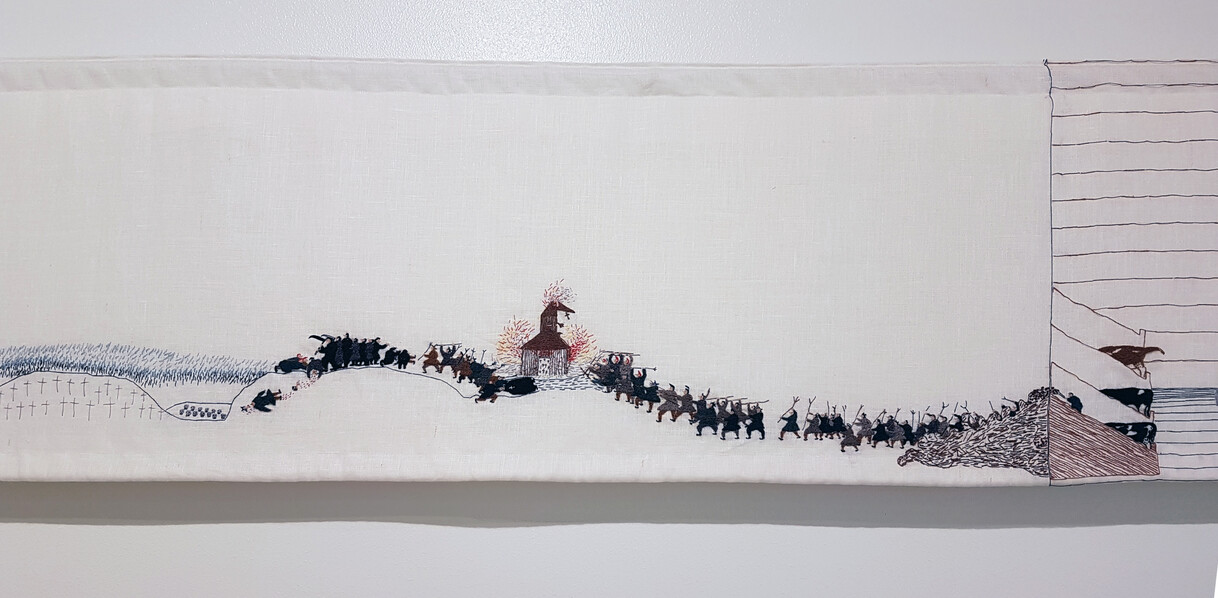

Marakatt-Labba situates Sámi bodies, stories and cosmology at the centre of her work.47 Her 24 metre-long embroidered mural Historja (History) FIG. 6 became globally renowned after its exhibition in documenta 14 in Athens 2017. It pictures a story of the Sámi people in myth and collective memory, based on both traditional oral narratives and modern written sources. It can be read either right to left or left to right: one beginning FIG. 7 features two goddesses overlooking several groups of sleeping humans, who are about to be created as earthly beings through the arrow of a third goddess, suggesting new generations connected to and guarded by avatars of the past. The other beginning opens with a forest scene, in which the trees are punctuated by small goddess heads. From the trees, wolves, bears and reindeer emerge, reinforcing the interdependency of human culture with nature, as foregrounded in Sámi cosmology. The multiple temporalities and directions of reading the imagery suggest the living presence of the past within the present, as well as the subjective interpretation of historical events.

As the scroll unfolds, technological developments, such as mechanised snow sleds, and key historical events, including the clash between Christianity and the Sámi religion, feature prominently. In particular, the frieze critically reimagines the 1852 Samí revolt in Guovdageainnu (Kautokeino in Norwegian), in which a group of Sámi rebels killed representatives of the Norwegian authorities and burned down the local merchant’s house in protest of their ties to the alcohol industry, which had impoverished the community. In retaliation, the two lead Samí rebels were executed and the others were imprisoned. The rebellion was one of the few violent reactions by the Samí against the exploitation policies of the Norwegian government, and it sparked a long period of repression and assimilation. In her reworking, Marakatt-Labba replaces the burned buildings with a church FIG. 8 as a symbol of cultural colonisation that is countered by her celebration of Sámi rituals and goddess figures throughout the frieze. ‘The Christian religion has done so much harm to us Sámi’, the artist recalls.48 It is worth noting that Marakatt-Labba has also produced Lutheran robes and textiles for church altars that mix Sámi and Christian practices. This is often overlooked in recent writing on the artist, which repeatedly and problematically characterises her work as ‘purely’ Indigenous.49 Her work rejects any pure or ahistorical characterisation of Sámi identity. Rather, it suggests what Hansen calls a ‘dual, dynamic space’ of encounter, relation and dialogue.50

Marakatt-Labba subverts patriarchal and colonial representations of history by inserting her work into a genealogy that recalls the legacies of Sámi duodji (traditional handicraft) and Indigenous traditions of feminine power. For example, Historja foregrounds the image of the ládjogaphir FIG. 9, a red horn-shaped hat that is traditionally associated with Sámi sovereignty and feminine authority in Sápmi. The diminutive scale of her figures and goddesses wearing the ládjogaphir subvert patriarchal historical representations in such landmark examples of narrative textile art as the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts a scene of battle in the European tradition. Tone Kristine Thørring Tingvoll observes that instead of the hero William the Conqueror, Historja centres the Samí people and their shared culture rather than any sovereign leader.51

Historja is characteristic of the artist’s work since the 1980s. Although the small-scale but horizontally extended format superficially resembles East Asian scroll paintings, Marakatt-Labba says that her work responds directly to the snowy vistas that characterise the far Nordic landscape: ‘I see pictures in panorama format when I’m out in nature […] When we Sami stay in nature, we see far and wide’.52 The extensive use of negative space aligns her work with the geography of Sápmi even as it relates it to an expanded definition of drawing. Caroline Elgh Klingborg observes that her ‘expanses of unworked linen are reminiscent of fields of snow or the sky, or perhaps just an emptiness that represents everything that remains unsaid or all the conflicts that remain unresolved’.53 In emphasising the experience of inhabiting this particular landscape, her work reframes the historical, and reactionary, associations of the Nordic with racial whiteness. Her holistic depiction of relationships among humans, animals and the land realign whiteness with the topographic features of a Nordic geography that is also the spiritual home of Sápmi. Her works, often directly related to the climate crisis in recent years, are decolonial in the way that they reject the conceptualisation of nature as other to culture.54 They recall that, as Gaski writes, ‘It is the particular role of Indigenous peoples to remind the rest of humanity of this crucial idea [of being mindful in contract with the earth] without which we cannot hope to survive’.55

Due to the monumental scale of Historja, Marakatt-Labba based the work on preparatory drawings, a practice that she only uses occasionally when faced with such large commissions.56 Despite the existence of the sketches, however, the frieze conveys a poetics of spontaneity and partiality in the sewn marks themselves, with their minute (mis)alignments and shifts of direction. Her irregular stitches foreground the partial, in the sense of both subjective positioning – a rejection of the impartiality of traditional history – and incompletion. Like a blank page, the linen surface of Historja signals not absence but possibility. Her unique embroidery practice can be viewed as a form of drawing, based on the radical open-endedness and multiple significations of the stitches. Unlike the Bayeux Tapestry, which was sewn by anonymous women, each mark in her work demonstrates a method that she devised and continues to improvise. Each stitch manifests the momentary decisions that allow her suggestive images to emerge. Marakatt-Labba has referred to her method as ‘painting’ with needle and thread, rather than drawing, however one can interpret this as a result of the historical priorities of art history and its canonical accounts of the relationship of modernist painting to personal expression.57 And yet her singular method certainly relates to drawing’s function as a connector among media. It is only through her suggestive and open-ended marks that the goddesses of the Sámi religion appear alongside modern humans and animals in this mythopoetic narrative.

Conclusion

Although radically divergent in cultural references and materials, the works of art discussed here participate in a dialogue that connects the subtle and handmade nature of contemporary drawing practices with subversions of patriarchal and colonial histories. These projects present counter-histories to the written narratives that have defined Indigenous peoples and celebrated colonialist violence. They problematise the idea of monumental or authoritative representations by remixing signifiers of cultural identity and Indigenous religion with myths, legends, fantasies and other playful idiosyncrasies. They resist spectacle and passivity by emphasising provisional presence and fragility. They counter colonial paradigms of knowledge by demonstrating the simultaneous presence of past, present and future. In different ways, they use drawing’s historical and contemporary associations with transience and privacy to politicise the commemoration of violent histories. Their interventions continue to resonate decades later. They inspire – often in unexpected ways – a deeper recognition of our own participation in or resistance to the hegemonic systems of knowledge and power. Drawing’s associations with vulnerability and openness encourage the viewer to decide how to respond to its aesthetic invitations. With its subtleness and humility, drawing has a unique potential to promote compassion across the social divisions created by histories of race and colonisation.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Nicole Eisenman, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kiki Smith, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Chelsea Staub, Loretta Yarlow, Hanna Horsberg Hansen, Garth Greenan Gallery and the anonymous peer reviewers for their assistance in researching and editing this article.