Black (re)turn

by Jade de Montserrat • Artist commission

by Edmée Lepercq

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 06.03.2024

In Toni Morrison’s debut novel, The Bluest Eye (1970), Pecola, a young Black girl growing up in 1940s Ohio, dreams that God will gift her a pair of blue eyes. She believes that these new eyes will change not only what she is forced to see, but also how she is seen by others. The artist Claudette Johnson (b.1959) has often cited The Bluest Eye as a key reference for her work, particularly the scene in which Pecola encounters a white Southern shopkeeper, whose ‘total absence of human recognition’ is only broken by distaste: ‘he does not see her, because for him there is nothing to see’.1 Like Morrison, Johnson centres her practice on addressing the ‘absence where black people should have been’ and, in her large-scale drawings of Black women, manifests the experience of being simultaneously highly visible and yet invisible.2

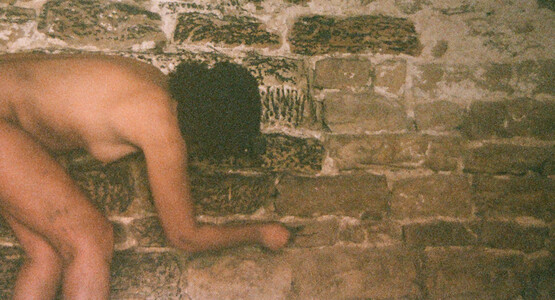

Three of these portraits are included in The Time of Our Lives, a group exhibition at Drawing Room, London, which brings together work by nine British women artists born between 1940 and 1988. Encompassing graphite, vinyl, watercolour, performance, installation and film, the exhibition showcases the breadth of drawing practices. Some drawings are no larger than a postcard, whereas others hang from the ceiling like banners, as in the work of Jade de Montserrat (b.1981) FIG.1. Drawing – with its relationship to fragility and erasability and its clear distinction between foreground and background – is uniquely well placed to speak to ideas of fragmentation, marginalisation and invisibility. This exhibition demonstrates the ways in which the exhibited artists have used the medium’s inherent qualities to grapple with sociopolitical issues. Several of those included either founded or were involved in activist groups, and their work reflects their use of consciousness raising to confront such topics as ableism, reproductive justice, gender-based violence and institutional racism.

Like Johnson, Sonia Boyce (b.1962) was associated with the British Black Arts Movement in the early 1980s, a group inspired by anti-racist discourse, which sought to highlight the politics of representation. She too has spoken of her drawings as a response to the limited depictions and tropes of Black women in sociocultural contexts. In Western art history, for example, when Black figures were depicted, it was often in minor or subservient roles, such as the attendant in Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Even when Boyce creates works that include paint on paper or other supports, she has referred to them as drawings rather than paintings. This is informed by her view that approaching the bare canvas is to ‘knowingly enter into the gladiatorial space of the artistic’ – an arena in which women and artists of colour must engage in battle not only with established hierarchies, but also their peers.3

By comparison, drawing, historically considered a preparatory medium, offered her a freer space. Mr close–friend-of-the-family pays a visit whilst everyone else is out FIG.2 is emblematic of her early drawings, with its use of self-portraiture set against a patterned wallpaper and text ribboning around the edge. Although the face of the woman, which turns towards the viewer, suggests a degree of weariness, it is the geometric pattern, faceless male figure and repeated handprints that convey the psychological state caused by unwanted touch.

Capitalising on the expressive potential of absence rather than presence, Sutapa Biswas (b.1962) and Johnson often use the white space of the paper support to articulate racial invisibility. Biswas’s Sacred Space FIG.3 comprises three separate portraits of her sister. While her face is carefully drawn and shaded in pencil, pastel and acrylic to capture variations in volume and skin tone, her hair, neck and shoulders are barely even outlined, suggesting a sitter with a fragmented self. Biswas, another member of the British Black Arts Movement, described her use of large white areas as a metaphor for institutional spaces, wherein ‘meaning could evolve to disrupt that which was already defined within it’.4 Similarly, in her large-scale self-portraits and depictions of her friends and relatives, Johnson leaves sections of the paper unmarked FIG.4. Such ‘blankness’ paradoxically emphasises the presence of the women, while also rendering them unknowable. ‘I’m not interested in portraiture or its tradition’, Johnson explained in 1990, ‘I’m interested in giving space to Blackwomen presence. A presence which has been distorted, hidden and denied […] I have a sense of urgency about our “apparent” absence in a space we’ve inhabited for several centuries’.5

In her meticulous, small-scale works, Soheila Sokhanvari (b.1964) seeks to save personal and national narratives of pre-revolutionary Iran from erasure. Sokhanvari often draws from photographs of Iranian female film and television stars, such as Parvin Kheirbakhsh (known as Forouzan), who was famous for her roles in films with vengeance plots and one-dimensional female characters. In one work, Sokhanvari projects a clip of Forouzan dancing onto a self-portrait in oil and 22-carat gold on paper. It is unclear whether the actor is free or trapped, as the liberation and joy suggested by her movement belies the world that she inhabits, which is ruled, as Sokhanvari explains in the wall text, by ‘crude oil consumption and love of gold’. Elsewhere in the exhibition, a series of drawings made using Iranian crude oil is shown FIG.5, each of which began life with a family photograph. Sokhanvari makes a first drawing based on this image, then makes a second drawing based on the first, and a third from the second, and so on and so on, gradually moving further away from the original photograph. Each iteration incorporates the drips, smudges and mistakes of the previous drawing, and culminates in the final exhibited work, which takes on a blurry quality suggestive of the unreliable nature of memory.

Another work that touches upon the role of memory in the construction of historical narratives is State of Emergency (1992) by Monica Ross (1950–2013). Ross was an artist and activist who participated in the anti-nuclear protests at Greenham Common in the 1980s and the art collective Sister Seven. Her practice is concerned with issues of time and the archaeology of the present, as well as the invisibility of working-class women throughout history. State of Emergency was an eight-hour performance and installation staged in an abandoned factory; it is represented here by a film and installation FIG.6. In the forty-two-minute film, Ross performs various sorts of manual labour – sieving dust, filling sacks, carrying them up and down stairs – as well as acts of mark making, such as frottage, rubbing and erasing. With this work, she invites us to consider how moments in the present are transformed, or not, into memory and history.

As an inexpensive activity that does not require a studio or much equipment, drawing is an innately accessible and adaptable medium. In her series FLAW FIG.7, Kate Davis (b.1977) draws tiny hyperrealist images of the detritus that gathers in the corners of kitchens onto crumpled envelopes. One particularly engaging example is covered with scribbles – a grocery list that includes ‘lapsang, manuka honey, prune juice, soap, Oatley [sic], salmon, paracetamol, cornflower, tampons’, as well as notes such as ‘Lotte’s counselling’, ‘MOT – before 18th Aug’ and ‘library thinking’ that hint to the artist’s daily concerns. In between these notes Davis has drawn a burnt matchstick, some unidentifiable seeds, a tampon applicator and a dried-up tomato stem. The work is an acknowledgment of a practice that is made of – and squeezed into – everyday life.

The artist and disability activist Lizzy Rose (1988–2022) made drawings about her experience of chronic illness during extended stays in hospital. In Exposing Trauma FIG.8, for example, she renders in watercolour and felt-tip pen the post-surgery selfies of scars and stoma bags shared by Crohn’s disease patients in the online communities of which she was a member. ‘I see this selfie sharing almost as an act of protest’, Rose wrote in an essay in 2016. ‘It shows a defiance to not conform with society’s vision of the perfect body and to challenge people’s perceptions of illness whatever the dangers to the sharer’s personal life’.6 Rose also highlighted in this essay the experiences of women in her community who, after sharing photographs of their experiences online, found themselves the subject of articles in the national press with such headlines as ‘Teenager with Crohn’s disease posts a brave selfie of her ileostomy bag to share her body positive message with the world’.7

In her 2004 watercolour and collage work Beautiful Ugly Violence FIG.9, the early British feminist activist Margaret Harrison (b.1940) similarly explores the relationship between representations of women in the public sphere and their private experiences. In this five-panel work, which is the result of extensive research, Harrison details the confluence of cultural factors that leads to gender-based violence. Divided into twenty-two sections – which include law, discrimination and honour killings – the work is a methodical list of newspaper clippings and written texts overlayed with familiar objects, such as irons, dinner plates, dresses, kitchen knives and guns that were used in violent acts against women. The contrast between the news stories and the delicate drawings point to the double edge of aestheticisation. As Harrison explains in the wall text, ‘things that are beautiful are not always beautiful but ugly underneath’. Elsewhere she notes, almost cynically, that the beauty of drawing is ‘a way of drawing people in. Instead of the “fist in the sky” all the time’.8

The institutional response to these artists and their practices has changed since the 1980s, when Johnson was developing her work while thinking of Pecola. In 2019 Sokhanvari held a solo exhibition at the Barbican, London; in 2022 Boyce represented Great Britain at the 59th Venice Biennale; and Johnson recently closed a solo exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, London, just steps away from paintings by Manet and Paul Gauguin. The Time of Our Lives shows how these artists have not only expanded the historical boundaries of drawing but also articulated something of the diverse experiences of living as a woman in the United Kingdom.