Blockchain manifestos: fighting for the imagination of a culture

by Charlotte Kent • Journal article

Launched by the leftist magazine the New Inquiry on 15th November 2017, Bail Bloc is a free software programme that allows anyone to use their computer to generate bail fund donations in the United States.1 This activist project – which arguably is also a socially engaged work of art – was designed by a large team comprising many of the leading practitioners in art and technology today, including Adrian Chen, Kate Crawford, Nora Khan, Trevor Paglen and Meredith Whittaker. It is designed to run in the background on your machine, silently consuming as little as ten per cent of its processing power, probably amounting to no more than a nominal increase in your energy bill; the website helpfully suggests that you ‘try using Bail Bloc in a place where an institution pays the bills’, such as ‘at your place of employment, at school, or at a gentrifying coffee shop’. The programme uses this electricity to perform calculations to verify transactions on the ‘blocs’ of the Monero cryptocurrency blockchain, for which it is rewarded with Monero ‘coins’ in a process called ‘mining’. Your computer then transfers these digital assets to a ‘wallet’ controlled by Bail Bloc, which consolidates the funds and regularly exchanges them for United States dollars, which it then donates. Needless to say, for those with access to excess capital, it would be faster – and more energy-efficient – to make an outright donation to a bail fund by cheque or credit card. But Bail Bloc makes the act of donating as easy and affordable as turning on your computer, while also helping to catapult ‘a radical criticism of bail into the public imagination’.

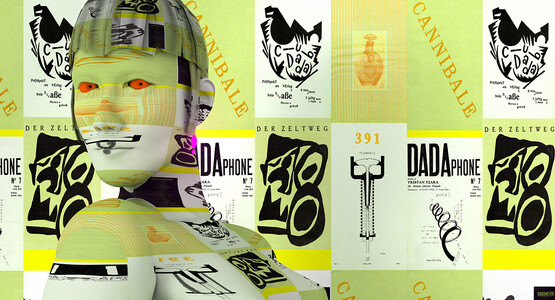

Throughout the explosion and subsequent implosion of the markets for blockchain-based cryptocurrencies and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that began in the spring of 2021, the present reviewer often wondered what the general public would think about blockchains if they had first encountered them through Bail Bloc, and not through speculative assets like Bitcoin and cartoonish ‘profile pic projects’, such as the Bored Ape Yacht Club and CryptoPunks FIG.1. NFTs were quickly established as the public face of the bleeding edge at the intersection of technology and art (which soon became bloodied and bruised). Their origins are often traced to a proposal by the artist Kevin McCoy FIG.2 and the technologist Anil Dash, who proposed using these unique, irreproducible digital records to symbolically stand in as a kind of (only questionably legal) ‘certificate of authenticity’ for inherently reproducible assets. Although NFTs have undoubtedly helped to create the perception of value for digital works of art in particular, in truth, they have always been part of a much larger, lesser-known story about technology and democracy. Helpfully, it is precisely this story that is reflected in the title of Amy Whitaker and Nora Burnett Abrams’s The Story of NFTs: Artists, Technology, and Democracy (2023) – the first book on NFTs to be published by a mainstream art press for a general audience.

Whitaker is an associate professor at New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education, and Human Development, where she specialises in the business aspects of the art world. By her own account, she has been researching blockchains since 2014. Abrams, who is a relative newcomer to the topic, holds a doctorate in art history from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, and is the Mark G. Falcone Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver (MCA), where she was previously lead curator for almost a decade. Unsurprisingly, then, their book is written through the lens of the contemporary art world – replete with comparisons to such familiar artists as Sol LeWitt FIG.3 – and functions primarily as an introduction to NFTs and blockchains for that community. It is based on the public programmes on which they collaborated for the MCA in 2021, including NFTs—WTF? and Putting the Fun in Non-Fungible Tokens, which aimed to demystify NFTs and the logic behind their creation and use.

One of the great virtues of The Story of NFTs is that it foregrounds the idea of multiple ‘stories’ of NFTs. Confusingly, the term can define a technology, an aesthetic, a market or a community. Moreover, the technology itself is related to various problems that are central to many fields, ranging from computer science to art, finance and law. The authors have chosen to simplify the discourse around NFTs into five ‘intersecting stories’, each of which is given its own section in the first chapter: ‘The knowledge story’, ‘The technology story’, ‘The money story’, ‘The democracy story’ and, of course, ‘The art story’. The authors clearly state that they see their book as a corrective to an overemphasis on the technology and money stories, choosing to focus instead on ‘the most poignant yet overlooked ones about knowledge and democracy’ (p.33).

From their origins in the wake of the global financial crisis in 2008, blockchains have been described by their inventors and proponents as a new, distributed way of authenticating digital information that cannot be edited or falsified by any single actor: this is ‘The knowledge story’. It is, however, a complicated one. For example, consider the ‘oracle problem’, which refers to the fact that blockchains can only verify that a piece of information was entered by a specific address and when; you would have to look off-chain to ascertain who entered it, or indeed if it is even true. Regardless, because they supposedly decentralise knowledge – that is, power – blockchains are often wrapped in the language of ‘democratisation’, appealing largely to anarchists and libertarians on both the left and right ends of the political spectrum. Given its focus on these inherently political ‘stories’, this book is not a history of NFTs per se; readers looking for that would be better served by Domenico Quaranta’s comprehensive Surfing with Satoshi: Art, Blockchain, and NFTs (2022).2 Whitaker and Abrams attempt, instead, to chart the questions that make NFTs relevant, including one of the most urgent quandaries facing our society: ‘What happens when the individualistic ideals of capitalism must be reconciled with the collective aims of democracy?’ (p.82).

Of course, to answer this question, we first need to define what is meant by ‘democracy’. In the world of NFTs, this at first seemed to mean getting rid of the traditional galleries that act as middlemen by shifting to new online platforms on which buyers and sellers could interact directly and with supposedly greater transparency.3 But as the authors admit, ‘it is easy to conflate economic participation and democratic access’ (p.113), eliding ‘buying in’ with becoming enfranchised. There is also danger in thinking of ‘democratisation’ as a kind of levelling of opportunity and success – concretised in the slogan ‘we’re all going to make it’ – instead of as a mechanism for negotiating the demands of conflicting interests and limiting the mob rule of the majority. Whether NFTs will democratise economic participation in the art world, let alone society, remains to be seen. To date, the NFT markets seem bent on replicating every inequality of the traditional art markets, including those of gender and race. More excitement is now focused on blockchain-based Distributed Autonomous Organisations (DAOs): social collectives that can loosely operate like investment funds but are managed by ‘smart contracts’, which automatically execute actions when certain conditions are met. Many DAOs issue tokens that can be used to participate in votes that govern the DAO, including about which works of art to buy for its shared ‘collection’. In their discussion of DAOs, the authors ask:

Do DAOs perpetuate a money story that is opaque and exclusive, much like the traditional commercial art market, or do they enable more people to participate in a system and provide equal access to ownership of an asset? The answer, of course, is that they do both. The capitalist pressure to sell a digital asset with the greatest possible value once again bears down on a more democratic ideal of shared ownership (p.85).

Although the book is generally optimistic about the possibilities of blockchains, this passage is one of several to highlight the tensions between the idealistic claims being used to argue for their mass adoption and the larger social systems in which they are necessarily embedded. It is precisely this tension that is ingrained in a work such as Dread Scott’s White Male for Sale FIG.4, which connects the idea of the non-fungibility of works of art to the capitalist history of the ‘fungibility’ of enslaved people.

The Story of NFTs attempts to resolve the contradictions between capitalism and democracy by pushing against the former in the name of the latter. After asking whether blockchains could help pool risk and generate a surplus that could be shared among a group, the authors observe: ‘What’s so interesting is that it is a market idea, but a market idea that syncs up with the solidarity economy, the forms of collaboration and resource sharing that could redistribute power not only in the arts but in society more broadly’ (p.102).4 This is precisely the kind of cautiously hopeful thinking about blockchains that has surfaced over the years in the work of forward-thinking arts organisations. These include Furtherfield, which proposed replacing the ‘do-it-yourself’ ethos with ‘do-it-with-others’, and galleries like TRANSFER and left.gallery, which shared profits among artists in their 2021 group exhibition Pieces of Me. The same optimism drives NFT companies like Looty, a platform that raises funds to restitute stolen artefacts, and thinkers such as Joshua Dávila, who runs the ‘Blockchain Socialist’ podcast and authored the 2023 book Blockchain Radicals: How Capitalism Ruined Crypto and How to Fix It.5

Although these topics are outside its scope as a primer, The Story of NFTs is nontheless an important introduction for the art world to this broader, sociopolitical vision of blockchains, beyond punks and pump-and-dump schemes. At best, it asks us to consider the story of NFTs as a story of ‘power and inclusion, of equity in the sense of ownership and also a sense of fairness or redistribution’ (p.112) – in ways that may even challenge the present legal and economic structures of property. As international humanitarian and ecological crises continue to unfold around us, a corner of the NFT world continues to look beyond Western frameworks of extraction towards alternative models that emphasise responsibilities instead of rights, care instead of control, people instead of profits. Let a million Bail Blocs bloom.