The publishing activities of Simon Cutts (b.1944) since the mid-1960s amount to an unparalleled contribution to the various fields of late modernist art, literature and design. This new compendium of articles, catalogue introductions and short texts – a number of which are previously unpublished – is concerned with the creative and practical extrapolations of what Cutts refers to as the ‘small press model’, which he outlines in a concise and eye-opening introduction:

Small Press activity arises from the need and resolve for a critical alternative to mainstream publishing. It is a search for its own methods of producing and making available, and at the same time a discovery and awareness of the ways others have contributed to the field.

From the ‘little magazine’ of poetry publishing, it often begins with writing and leads to individual publications and books, together with accompanying printed ephemera of an often unclassifiable nature: having discovered the means of production, it is possible to improvise and delight in the extensions of the idea of publication (p.9).

The notion of ‘extending the idea of publication’ is crucial to Cutts’s work and to the thrust of this text. As his introduction continues, ‘the small press platform can extend by example into other ways of working, through the application of its spirit of self-invention and economy of means: the primacy of editorial reduction’ (p.10). It may, for example, give rise to the creation or curation of three-dimensional works of art by suggesting ‘the editing of more physical spaces as extensions, organisationally and economically, of what begins with the book’ (p.9). Thus, the small-press model becomes applicable over a far wider range of contemporary art than the world of independent, avant-garde literary publishing from which it arises.

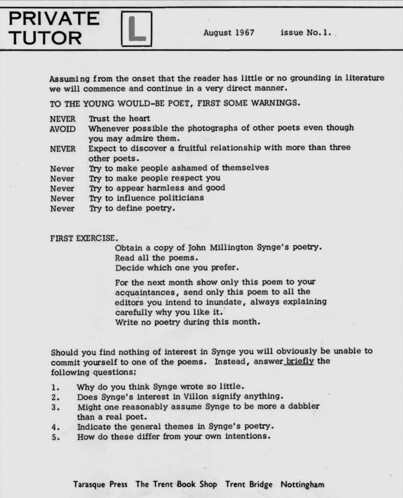

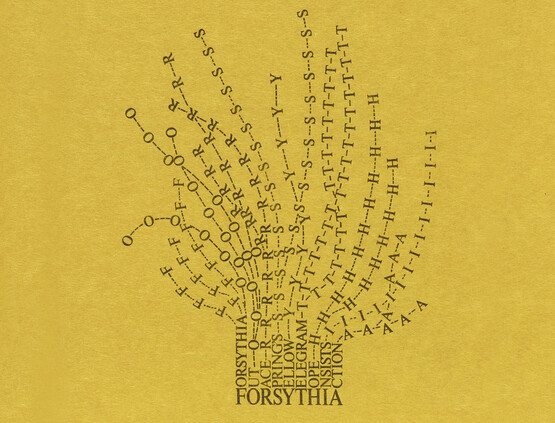

Cutts’s first significant publishing project was Tarasque Press, a magazine and publisher that he co-managed with Stuart Mills in Nottingham between 1964 and 1971. A longer-term focus has been Coracle Press, which he has operated with the writer and artist Erica Van Horn since 1975, first in London, then Nottingham and, since 1996, in County Tipperary. Cutts’s formal approach to small-press publication is openly indebted to Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006), with whom he frequently collaborated. The post-constructivist minimalism and the romantic preoccupation with nature and post-concrete poetics that defined Finlay’s practice are threaded throughout Cutts’s work. This is particularly evident in his use of printed objects as extensions of poetic form through sculptural, visual, tactile and other material effects that enrich and extend semantic meaning. For example, Cutts’s 1984 book mirroirs has endpapers that are made of mirrored paper FIG.1. Finlay was also a formidable opponent of the ‘neo-dada’ aesthetics that he associated with the 1960s, and his acerbic attitude to this and other creative idioms he saw as sloppy or informal influenced the waspish critical writing found in Tarasque publications – along with the very English snark of Wyndham Lewis’s magazine Blast (1914–15). The Tarasque poem-sheet series Private Tutor FIG.2 is a case in point: envisaged as a kind of exam-prep guide for young poets, the first issue (1967) instructed them: ‘NEVER trust the heart’ (p.23).

The Small Press Model is divided into three sections. The first touches upon the origins of Cutts’s publishing projects and outlines some of the ways in which they have extended the aesthetic possibilities of small-press publications, generally stretching its associated practical and economic models in the process. The second, ‘Equivalent Spaces’, explores the architectonic and sculptural possibilities of the published object before moving onto the ways in which three-dimensional spaces – such as small bookshops or independent publisher fairs – can condition encounters with the book as object. The final section, ‘Particular Dislocations’, presents a series of tributes to, or reflections on, important figures in Cutts’s creative life: the artists Stephen Skidmore, Stephen Duncalf and Roger Ackling, the gallerist Brian Lane and the poet Jonathan Williams. It then goes on to outline some of Cutts’s more ambitious three-dimensional ‘publishing’ projects.

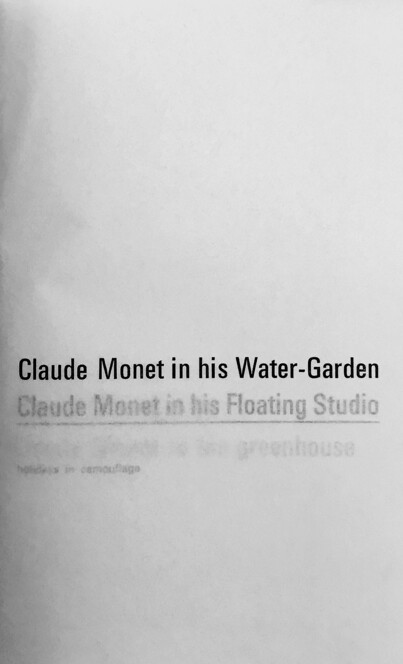

A standout text from section one, ‘The metaphor books’ (2009), considers Cutts’s history of creating books with visual and otherwise material qualities that extend the work of linguistic reference and metaphor. ‘Claude Monet in his water-garden’ FIG.3, for example, consists of a series of translucent pages that allow the reader an opaque glimpse of the text on the following page, as though peering at a watery surface. Thus ‘Claude Monet in his Water-Garden’ on one page gives way to ‘Claude Monet in his Floating Studio’ on the next. The translucency of the paper and the semi-veiling of the language beneath become metaphors for Monet’s capacity to make solid things appear permeable to light and atmosphere.

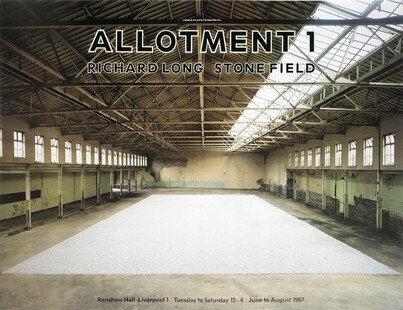

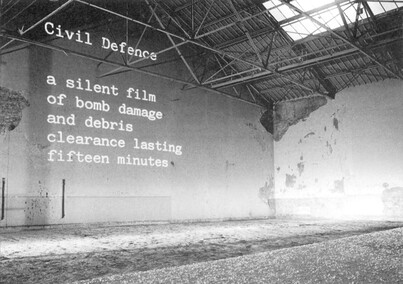

Other writings in the first section touch upon what Cutts calls the ‘organisation of physical space […] as a form of publishing’ (p.13). Among the various exhibitions, galleries and comparable ventures established by Coracle was the remarkable Allotments project. In 1987 Cutts requisitioned Renshaw Hall, a vast, former warehouse space in Liverpool, and invited artists, musicians and other creatives to exhibit there. The result was a series of overlapping works that were intended to bear some affinity to the sequential issues of a magazine, or the individual sections of text and image within a single issue. For Allotment 1: Stone Field FIG.4, Richard Long created a huge rectangle of stone in the centre of the space, while the unrealised Allotment 2 was set to include a concert by the industrial band Test Department. Allotment 3 FIG.5 comprised a poem by Cutts projected on the wall of the hall beyond the edge of Long’s Stone Field for a single evening. The idea, Cutts explains, was that ‘multiple individual projects would take place simultaneously, alongside a small site hut for each of them […] producing a veritable magazine of activity, an anthology of published parts’ (p.61). This is one of the clearest examples in the text of how the qualities of small-press publishing can be brought to bear on the larger scales often afforded to contemporary art.

Section two opens with pithy ruminations on the sensory delights that arise from handling and observing certain forms of small-press publication. ‘On the flapability of the pamphlet’ extols the pleasures of waving a pamphlet in the air and experiencing how ‘it controls the draught between its pages, like an instrument, using the air generated as it is waved’ (p.89). ‘A concertina of concertinas’ describes the titular booklet-type as ‘the closest to sculpture in a reductive way that the printed artefact ever comes’ (p.89). Conditioned by these examinations of the physical dynamics of reading, one can approach essays such as ‘The format of the small shop’ as though the three-dimensional environments they describe, are in fact, formats for publication. In this essay, a photographic illustrations shows how Duncalf dressed the Coracle Press shop window in 1984 to resemble Edward Hopper’s Seven A.M. (1948) FIG.6. It is an interesting exercise in translating a two-dimensional image into physical space.

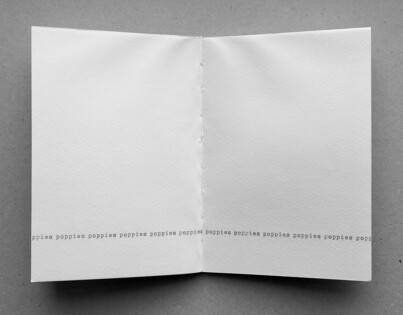

The final section’s tributes to various friends and peers position some interesting reflections on Cutts’s three-dimensional poem-objects and publications, making clear his belief in the ‘network’ as ‘the true base of modernist work’, including his own (p.11). Of particular interest is ‘A History of the Airfields of Lincolnshire’ FIG.7, a poem in aluminium lettering on slabs of excavated concrete runway, consisting of the single, repeated word ‘poppies’. The same piece appeared in page-based form in 1990 FIG.8, thus demonstrating a concise progression from the small-press publication to the work of art at large in the world. In both cases, the one-word poem refers to the poppies that had grown on ‘the old concrete airfields in that part of Britain where the planes took off and landed during the Second World War’ (p.44). But in its new context, the replacement of the page with the physical runway surface referred to in the title musters an intriguing symbolic density, whereby this small strip of concrete becomes, as it were, a sign for itself.

If there is a criticism to be made of the composition of this book, it is that the collation of pre-existing material sometimes leaves the overarching focus of the writing hard to grasp. The reprinting of numerous catalogue essays, for example, is a strange decision when many of the works of art or events under consideration are missing. Additional notes of a descriptive, contextualising kind are not provided, a move that inevitably comes across as exclusionary in places. This gripe aside, The Small Press Model is an invaluable document of a practice that has consistently prised open the boundaries between different modernist media. Its great interest lies in presenting the small-press model as a creative approach that, although rooted in independent literary publishing, is potentially applicable across a far wider field of contemporary art.