Penny World

03.08.2022 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Verity Mackenzie

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 10.11.2023

‘There is nothing that intelligent humour cannot resolve in gales of laughter, not even the void […] Laughter, as one of humanity’s most sumptuous extravagances, even to the point of debauchery, stands at the lip of the void, offers us the void as a pledge’, so claimed the French writer and occultist Pierre Piobb in 1936.1 Writing three years later, in what would become the introduction to his Anthology of Black Humour (1940), André Breton introduced the term ‘black humour’ as it is understood today, describing it as ‘the mortal enemy of sentimentality’.2 A similar comic characterisation can be found early on in the retrospective of work by Sarah Lucas (b.1962) at Tate Britain, London. The visitor is welcomed to the exhibition by The Old Couple FIG.1: a pair of plain wooden kitchen chairs, one embellished with an upright wax dildo and the other with a set of false teeth. The work’s sadomasochistic potential is evident, even as the suggestion of age and familiarity signal the end of sex. Wholly unsentimental, there is a Freudian sensibility and a dark humour in the conjunction of furniture, a phallic stand-in for the male body and a prosthetic smile with bared teeth.

The ‘laughter’ of the exhibition recalls the canned euphoria of nitrous oxide, as indicated by its title: happy gas. It hints at Walter Benjamin’s concept of ‘profane illumination’ – an altered state of consciousness central to Surrealist experience with hidden aspects of the everyday, which Benjamin compares to perceptions otherwise accessible only through religious ecstasy or drugs.3 Yet Lucas goes beyond both the divine and the narcotic in her negotiation of the quotidian. In Pairfect Match (1992), for example, a centrefold from the now-defunct tabloid paper Sunday Sport is enlarged and framed on the gallery wall. The double spread invites readers to take part in a game: a ‘breast quest’, in which they must connect a set of images showing disembodied female faces to a parallel series of their cropped breasts. The combination of text and image is indicative of how language as a material is central to Lucas’s practice – for her, ‘everything is language, including objects’.4

Indeed, it is this interest that appears to structure the organisation of the exhibition. The focus on words and portraiture – always an objectifying genre in Lucas’s practice, best seen in her self-portraits – in the first room gives way to the tights and chairs in the second. A parade of seated anamorphic figures made from distended hosiery runs the entire length of the space FIG.2. Room 3 focuses on Lucas’s use of concrete and includes oversized casts of a courgette FIG.3 and sandwiches, while Room 4, ‘Cigarettes’, brings together works comprising the material that signals perhaps her greatest love of all: smoking.

For Breton, by way of Léon Pierre-Quint, humour is a ‘“way of affirming, above and beyond the absolute revolt of adolescence and the internal revolt of adulthood”, a superior revolt of the mind’.5 This precise form of profane illumination, which depends on the jolt of the familiar made strange – here, in the hands of a woman artist – signals Lucas’s references to Surrealism. In a 1966 essay Lucy Lippard referred to Surrealism as ‘housebroken Dada […] chaos tamed into order’, considering it to be a trained form of the anarchic movement from which it was born.6 Lippard’s words open the door to the domestic, welcoming visitors of Lucas’s exhibition to a world of tabloids, chairs, chickens, sandwiches and concrete vegetables. And yet her work is not quite tame.

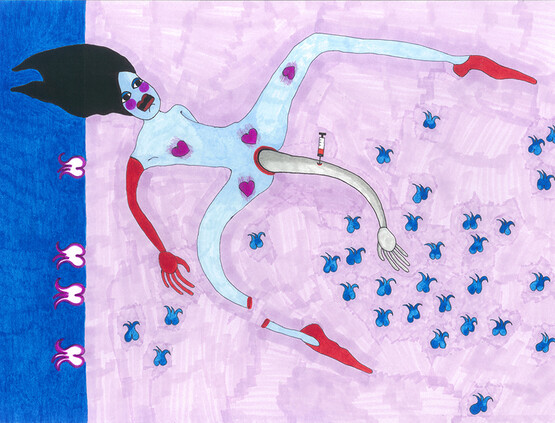

This is evident in the changes Lucas has wrought on tights and shoes and lavatories; these recurring forms are reconfigured and endlessly anagrammatic. The iconic occupant of domestic space – the woman herself – is reimagined in nylon tights, which have been solidified in bronze or papier mâché to suggest the curvilinear forms of hysterical and liberating laughter. Over time, Lucas has moved from the soft to the rigid: from Bunny FIG.4, which is made up of kapok, stockings and bulldog clips, to Hysterical Attack (Mouths) (1999) and Hysterical Attack (Eyes) (1999), sculptures papier-mâchéd onto chairs, to a parade of cast bronze and concrete forms. These are exemplified by TITTIPUSSIDAD (2018), in which a multi-breasted polished bronze figure, with impossibly attenuated, bendy legs, arches its back over a cast concrete chair, polymorphously perverse – not least in its title.

In his introduction to the Anthology of Black Humour, Breton asks ‘You want the rest of humour’s anatomical parts?’7 and Lucas, who recognises that ‘there’s no substitute for genitalia in terms of meaningfulness and a bit of edge’ (p.155), provides them.8 In the next room the photograph Prière de Toucher (2000), which reveals the artist’s nipples through two small holes in a torn grey t-shirt, has been enlarged and plastered across one wall. The title is a reference to Marcel Duchamp’s cover for the exhibition catalogue Le Surréalisme en 1947, for which the artist bought a thousand foam rubber breasts and attached one to the front of each copy, with the words ‘PRIÈRE DE TOUCHER’ (‘PLEASE TOUCH’) on the back.9 Further on, Michele, Pauline and Sadie (all 2015) appear ‘topless’.10 The plaster casts of legs, missing their torsos, are displayed straddling a desk, a lavatory and a chair with cigarettes in their assholes. These ‘muses’ are a nod to Lucas’s exhibition in the British Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale, I SCREAM DADDIO, in which they appeared, cast in plaster scrim and shocking against the yellow walls, suggesting sunshine or the custard yellow of îles flottantes.11

Throughout the exhibition there is the sense that, for Lucas, such shows are themselves full-scale installation works, as was also the case in her Venice presentation and her 2000 exhibition at the Freud Museum, London – both of which are quoted here. Reimagined for Happy Gas, the psychoanalyst’s couch becomes an array of mismatched chairs ‘to hang the exhibition […] on’ (p.15); the pudding yellow of îles flottantes is replaced by the red sky in a series of self-portraits, which have been turned into digital wallpapers. In the Red sky photographs FIG.5, the artist is pictured wreathed in smoke, and doubled or blurred in a series of double exposures. A form of laughter emerges from the sequence of portraits, evoking Dadaist wordplay and resembling a kind of knowing hysteria. An interest in puns – linguistic and visual – extends across virtually all of Lucas’s works, not least in the title of her exhibition in Venice – a high-pitched plea for ‘ice cream, daddy’ – as well as the sculpture Mumum FIG.6, which recalls ‘the mother’ in a lap of breasts and references Louise Bourgeois.

The last room displays Lucas’s cigarette works, including The Kiss (2003), which is a play on Rodin’s 1882 marble sculpture of the same name, featuring stacked wooden chairs for lovers, with genitalia made out of cigarettes. In This Jaguar’s Going to Heaven FIG.7 – a dismantled, cigarette-covered car that appears to be caught mid-crash – Lucas associates her love of smoking with Freud’s idea of Eros and Thanatos, the ‘life and death drives’: opposite instincts that operate beyond the pleasure principle to stop her from giving up smoking. For Benjamin, ‘one need only take love seriously to recognize in it, too a profane illumination […] The dialectics of intoxication are indeed curious. Is not perhaps all ecstasy in one world humiliating sobriety in that complementary to it?’.12 Smoking, giving up smoking, not giving up smoking. Lucas is counted among the Young British Artists (YBAs), so it is not surprising that the works in this room also arguably recall the group’s early patron, Charles Saatchi, and his advertising firm’s 1990s Silk Cut cigarette campaign, which was targeted at women. The slashed silk of Paul Arden’s most iconic image evoked a wordplay on Silk Cut / silk cunt, and Lucas’s ‘muses’ make the same connection, but on a Freudian level: sex, their own cast genitalia and death, as promised in a cigarette.

If, according to psychoanalytic theory, the ‘muses’ are all penis envy, there is also a conscious Freudian underpinning to Lucas’s ‘reasons for making a penis: appropriation, because I don’t have one; voodoo; economics; totemism […] fetishism; compact power; Dad’.13 At the same time, the irreverence of her comic juxtapositions recalls Freud’s definition of joking as ‘the disguised priest who weds every couple […] He likes best to wed couples whose union their relatives frown upon’.14 This tendency to unite the seemingly disparate is visible in her impertinent conjunctions: of an onion or a chair, but also her own body and a banana, as in Eating a Banana (1990), or fried eggs in Self Portrait with Fried Eggs (1996). The overall spareness of such works is evident in the curating of Lucas’s show at Tate. At only four rooms long, it is compressed but full of potential, like happiness in a canister.