Nicole Eisenman: What Happened

10.01.2024 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Anna Campbell

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 26.02.2020

For much of Western civilisation’s history, painting had a clear purpose. At the hands of master practitioners and their disciples, its role was to provide a window onto the world. Sometimes it recorded what was already in existence: the people, landscapes and objects of its time. Elsewhere it channelled the narratives of history, mythology and religion, seeking to inspire and edify its viewers. Whatever its subject, it took pride in its seemingly unrivalled ability to cleave to reality, in all its idealised beauty.

Then, in the nineteenth century, came photography. ‘From today, painting is dead’, the artist Paul Delaroche reportedly declared after seeing a daguerreotype for the first time. With the medium’s raison d’être seemingly quashed by the purported veracity of the camera, anxiety set in. Some extolled painting’s emotive potential, reconceiving it as a direct expression of the nervous system. Others divorced it from reality altogether, transforming it into a vehicle for the surreal and the sublime. Despite these efforts, doubt continued to linger. As Minimal and Conceptual art took centre stage in the 1960s, Ad Reinhardt proclaimed he was making ‘the last paintings which anyone can make’.1

History typically revisits painting’s story again in 1981, when the Royal Academy’s controversial exhibition A New Spirit in Painting seemed to promise a fresh start. On both sides of the Atlantic, a new breed of practitioners responded to its rallying call. In Germany, Martin Kippenberger and Albert Oehlen took an axe to the medium’s pedestal, unravelling its traditions to produce a genre irreverently dubbed ‘bad painting’. In America, artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and George Condo filled their canvases with new, wild visions of the human form. For a brief halcyon period, painting was king once more – so the tale goes – before the 1990s descended into postmodern plurality.

It is at this point that the Whitechapel Gallery picks up the narrative. Radical Figures: Painting in the New Millennium celebrates ten international artists who have breathed new life into the medium – specifically within the genre of figurative painting – during the last two decades. The ghost of A New Spirit lingers unavoidably in the show’s conception: indeed, a small homage to the latter is staged in an adjacent room. It could be argued that, for many, the millennium hardly seems new. Nonetheless, the title offers an optimistic endorsement of painting’s future: should it continue to evolve for another thousand years, one infers, 2020 will seem positively primeval.

If painting was once threatened by photography, the exhibition’s catalogue essays and wall texts posit a new omen: digital media. In a world of instant gratification, the show suggests, painting offers a slower alternative – a corporeal, tactile means of looking, feeling and understanding. First to the witness stand is Cecily Brown: an artist whose work truly embodies this dictum. Relishing the sensual properties of oil paint, her rollicking panoramas flicker seductively between figuration and abstraction, alive with the carnal, physical pleasures of mark-making FIG.1. Two are based on the theme of ‘shipwreck’ after Théodore Géricault: a metaphor that, in so many ways, seems all too apt amid today’s apocalyptic headlines.

Artistic, social and political history offers a point of entry for many others in the exhibition. Daniel Richter – formerly Oehlen’s studio assistant – navigates seamlessly between contemporary news stories, internet pornography and subversive allusions to Romanticism and Abstract Expressionism FIG.2. Michael Armitage, whose presentation is surely one of the strongest, channels Paul Gauguin and Edvard Munch in his glowing, deeply poignant meditations on sexual politics in East Africa FIG.3. Sanya Kantarovsky’s darkly humorous figures cower in shame, haunted by everything from Christian iconography to Russian poster designs. Tala Madani draws upon her Iranian heritage in a series of canvases confronting male and female stereotypes, simultaneously comedic and grotesque FIG.4.

With so many competing narratives at play, the curators’ separation of these artists does little to encourage free-flowing conversation between them. Nonetheless, the downstairs gallery feels vibrant and diverse. Upstairs, a room dedicated to the various artists’ studio practices provides a brief but enlightening interlude. Well-thumbed books and journals mingle with notes, drawings, fabric samples and postcards. A film by Armitage demonstrates the traditional methods used to produce Ugandan lubugo bark cloth – his unconventional canvas of choice. Such offerings serve to nourish the exhibition’s thesis: that painting today remains an unspoilt refuge of analogue process.

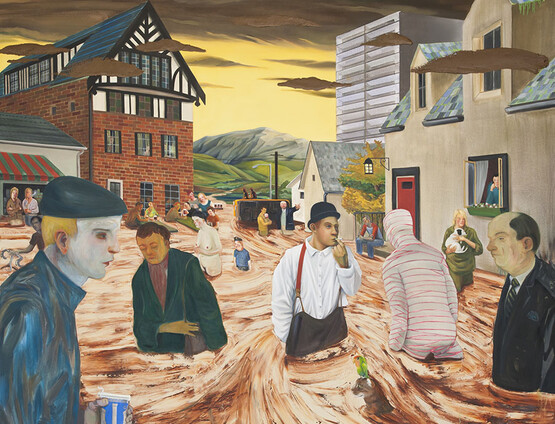

This idea is certainly central to the work of Nicole Eisenman, who describes herself as ‘a developer building twelve-storey high-rise condos on the ruins of art history’.2 The notion of art as labour is writ large across her sprawling narrative scenes, forged with the painstaking intricacy of Renaissance frescoes FIG.5. Dana Schutz makes a similar point in her early Goya-inspired canvases, whose voracious, cannibalistic subjects seem to allegorise the creative process. Christina Quarles and Ryan Mosley, by contrast, are more interested in paint as a vehicle for capturing shifting layers of personal identity. The same is true for Tschabalala Self, whose figures not only carve a new space for representations of the Black body, but also pose vital challenges to hierarchy of canvas and pigment FIG.6.

Despite its various thrills, Radical Figures remains underpinned by an unshakeable question: had figurative painting ever really gone away? Decried as ‘unfashionable’ during the 1990s, in practice it was alive and well. Indeed, the influence of its key exponents – including Jenny Saville, Paula Rego, Luc Tuymans, Marlene Dumas, Peter Doig and Chris Ofili – resounds throughout the exhibition. Back in 1981, A New Spirit in Painting had prompted similar concerns. For all the anti-painterly rhetoric of the 1960s and 1970s, the medium had arguably experienced one of its greatest periods at the hands of artists such as Frank Auerbach, David Hockney, Georg Baselitz, Jean Dubuffet and Francis Bacon.

The work of the last, in fact, provides one possible way of comprehending the works on view here. Operating over a century after the invention of the camera, Bacon was one of the first artists to paint how it felt to be human in the age of photography, capturing the visceral sensation of flesh passed through a lens. Something similar, perhaps, emerges in Radical Figures. Maybe the new millennium will look back on this generation as artists who – through the most immediate and pliable substance at their disposal – described the messy, fragmented experience of being alive in the digital era. Paint, after all, was the original virtual reality: the canvas the original screen. In this sense, its purpose is unchanged – it remains, as ever it was, a window onto the world.