Penny World

03.08.2022 • Reviews / Exhibition

by Millie Walton

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 23.08.2023

For the Swedish artist and educator Moki Cherry (1943–2009) there was no division between life and work. Together with her husband, the jazz musician Don Cherry (1936–95), she cultivated an all-encompassing creative practice that incorporated writing, performance, textiles and paintings, as well as domestic chores, raising her children and teaching. Cherry described their approach as ‘improvisation’, a term befitting the spontaneity and malleability of their nomadic lifestyle, which involved carrying only the essentials.1 For Cherry, this included her sewing machine and fabric, which was lightweight and easy to transport. As she put it: ‘fabric was a great, practical solution. Roll it up, put it in a couple of duffel bags. Go on tour with the family and musicians in a minivan’.2 She was also prone to picking scraps of material and old clothes out of rubbish bins, which she would then wash and stitch into vivid tapestries that adorned the spaces they lived in and the stages they performed on. For Cherry, the tactility of materials, as well as their previous lives and narratives, were just as important as her final compositions, if not more so.

Cherry’s improvisational approach and gift for storytelling are the focus of the solo exhibition Here and Now at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London (ICA). The exhibition title refers to her interest in Tibetan Buddhism, which she studied in the 1970s. In Western society, the idea of living in ‘the present moment’ is arguably, still today, a form of counterculture: it is the antithesis of our digitally absorbed, screen-bound lifestyles. For Cherry, it meant being sensitive and adaptable to the environment around her, but it was also a form of resistance against the societal roles that she was expected to play as a woman, wife and mother.

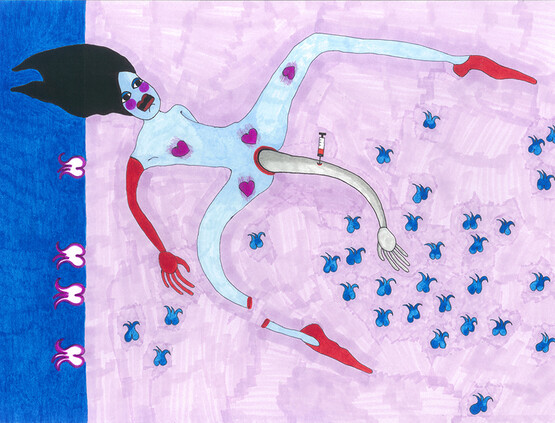

On the surface, her exuberant paintings and textiles – with their silky textures, wavy psychedelic forms and hybrid creatures – appear, if not apolitical, then more engaged in the realms of imagination than feminist discourse. However, for the artist, fantasy was a method for interacting with and finding new ways of seeing the world. Take, for example, a curious pair of untitled paintings, which appear to depict the inner machinations of unfamiliar body parts FIG.1: a network of red lines akin to veins, fleshy organ-like shapes and a grey mass resembling a brain. As with much of Cherry’s work, these paintings offer a contradictory viewing experience: the bright colours and flat, graphical style create a readable aesthetic that is not dissimilar to illustrations in children’s books – her work was often used in the educational workshops that the Cherrys ran – while the image itself is shapeshifting and ambiguous. Indeed, the majority of works included in the exhibition are untitled. As the artist stated: ‘I cannot name my paintings since they very seldom, yes never, symbolize a particular historical moment. They are all dedicated to all the invisible powers that are ruling man and the universe’.3

However, other works appear to take a pointed aim at convention. One of several vitrines displaying a selection of handwritten texts, sketches and photographs includes a pen drawing of a strange mechanical contraption FIG.2. A wheel with legs powers a headless robot that ‘eats’ with a knife and fork while simultaneously defecating; hovering above is an amiable winged monster with voluptuous lips, holding a sign that reads ‘WHO ARE YOU WORKING FOR?’. A question rather than an accusation, it reads as simultaneously anti-capitalist and existential. Nearby, the painting Communicate, How? FIG.3, depicts a bewildered creature with red eyes – somewhere between a frog and monkey – dressed in a quaint yellow top with a frilly collar. Above it floats another question: ‘COMMUNICATE, HOW?’. This can be read in multiple ways: as the concern of an alien being in a wholly new environment, or the anxiety of an artist who found herself consistently relegated to the fringes of the art world.

Although Cherry exhibited her work in galleries and museums during her lifetime, she was largely dismissed, along with other artists working in craft practices, as unworthy of serious attention. This was no doubt compounded by her slippery subject-matter, intense colour palette and the density of her imagery at a time when Minimalism was in vogue. Within this context, Communicate, How? might portray less an inability to express oneself than an impossible situation in which the listener or audience is unable or unwilling to comprehend. Perhaps unsurprisingly, she found that children – their minds still malleable enough to see beyond prescribed social scripts – often made for a more accommodating audience. As she wrote during a writing workshop with the feminist art historian Arlene Raven (1944–2006), ‘I have not been very successful in the established art world, but children have always been great supporters, and they have let me understand the work is OK, and [to] never lose hope’.4

The same year that she completed this painting, Cherry moved with her husband into an old schoolhouse in Tågarp, Sweden, which became, as well as their home, an educational centre and informal creative retreat for artists, musicians and local children. The exhibition includes video footage from a six-episode television programme called Piff, Paff, Puff produced by the Cherrys for Swedish public television in the early 1970s. Aimed at young audiences, the show comprises a series of scenes filmed in the schoolhouse. In one, a campervan of children arrives to be ushered into a kind of playroom filled with Cherry’s work, including a hanging sculpture with layers of sagging forms made from silk, satin and polystyrene balls. The same sculpture FIG.4 is hung close to the aforementioned paintings; its drooping shapes appear like breasts or innards, simultaneously sensual and grotesque. It was originally created for the group exhibition Utopias and Visions 1871–1981 at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, in 1971, which focused on the Paris Commune, the revolutionary government that ruled Paris in the spring of 1871. The Cherrys ran daily workshops for Utopias and Visions inside a geodesic dome installed in the gallery courtyard, which also served as a makeshift home and studio. However, in the video footage of the old schoolhouse, the sculpture loses its suggestiveness, instead becoming a component of soft play – a kind of jovial punching bag or an allusion, perhaps, to the long-suffering, ever-adaptable mother figure – as children dash around and beneath it while Don sang at the piano.

The curators of the exhibition – Cherry’s granddaughter Naima Karlsson, and the ICA Assistant Curator Nicola Leong – have tried to recreate some of this energy in the show. Textiles are suspended from the ceiling, presumably in an attempt to transform the sterile setting into a more immersive environment, but the height and distance at which they are hung creates an overall sparseness and inaccessibility. The exuberance of Cherry’s work is still felt – notably in the wild, jovial face of a three-eyed dragon with colourful strips of fabric trailing from its gaping mouth in a large tapestry FIG.5 and D.C FIG.6, a portrait of Don with his tongue out and the body of a white bird forming the shape of his nose and eyebrows.

However, there is simply not enough variety in the works on display to convey the expanse of Cherry’s creative output. This is admittedly a difficulty with exhibiting any genre-defying artist in a conventional gallery space: how to capture creativity that explodes in all direction, typically in non-traditional art spaces, such as the home or classroom. Nevertheless, it is amiss that apart from a beaded tunic, none of the clothes and costumes Cherry made are present, considering she originally trained as a fashion designer and used her skills to dress her family, including Don and his band. The exhibition lacks recordings of the couple’s collaborative performances, apart from the archival documents in the vitrine displays, which are oddly traditional in format compared to the content they hold. But Cherry’s inventiveness is difficult to repress. At the core of her work is a refusal to be restrained by any social role, artistic practice or space: she made objects that were designed to be multifunctional and appreciated by all.