Communist witches and cyborg magic: the emergence of queer, feminist, esoteric futurism

by Amy Hale • June 2022 • Article commission

The Milk of Dreams, the exhibition in the Giardini’s Central Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, wove a compelling story about how women engage with magic and spirit. Its curator, Cecilia Alemani, made this clear with a space titled ‘The Witch’s Cradle’ FIG. 1, which took its name from the experimental film made in 1943 by Maya Deren (1907–61).1 Yet although many of the historical artists included in exhibition, such as Leonora Carrington (1917–2011), Dorothea Tanning (1910–2012) and Remedios Varo (1908–63), are known for evoking enchantment and otherworldliness in their work, magic is and always has been a strategy and tactic for living. It is a form of creative resistance, a way of understanding the universe and navigating it, a deeply relational way of being and collaborating with human, non-human and extradimensional entities and even machines. Alemani’s supporting curatorial statement for The Milk of Dreams – named in homage to Carrington’s beguiling and occasionally jarring children’s book of the same name – focuses on artistic responses to change and transformation: arguably the central tenet of all magic.2

For the biennale, Alemani brought together a shining collection of artists, mostly women, historical and contemporary, to explore ‘kinships and affinities between artistic methods and practices, even across generations, to create new layers of meaning and bridge present and past’.3 Arguably an undercurrent of the exhibition was the presence of esoteric thought and practice and its influence on women’s art. In fact, it seems that the more that women’s contributions to the history of modern art are uncovered, the more esotericism becomes a key part of the discourse. Yet in exploring the role of women artists in what is broadly called ‘esoteric art’, the standard scholarly history of esotericism itself, particularly in the West, is transformed, and the male-centred narrative is disrupted. The Venice Biennale was just one element in a new emerging chapter of women’s esotericism in art, one that expands the modern language of magic outward into a series of creative, empowering futures of psychedelic cities, communist witches, plant-human hybrids and beautiful monsters. This responsive and intersectional collection of artists shows women, once again, reconceptualising the modern conventions of the esoteric, the occult and the unseen.4

Changing interpretative contexts of esoteric art

Esoteric art is certainly having a cultural moment, striking a chord with both curators and the general public, and the recent surge is provoking a great deal of commentary.5 Although interest in the theme has increased steadily since the exhibition Dark Monarch at Tate St Ives in 2009–10, since 2016, occult and esoterically themed exhibitions have proliferated.6 The 2018 exhibition of works by Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) at the Guggenheim, New York,7 was a staggering success, followed by the touring exhibition Not Without My Ghosts: The Artist as Medium, which opened at Drawing Room, London, in 2020,8 The Botanical Mind at Camden Art Centre, London,9 and Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 2022, to name just few of the most noteworthy events.10 Most of the discussion surrounding these shows uses the term ‘spirituality’, which appears to be a euphemistic way of evading a discomfort with the terms ‘esoteric’ and ‘occult’. Yet these exhibitions are increasingly forcing the acknowledgment of a specific and persistent undercurrent of heterodox religious belief and practice in the West, where accepting the influence of esoteric practice and thought is persistently awkward. Esoteric art is a wide-ranging term that is used to retrofit a variety of themes and artists into a more coherent whole, from Renaissance alchemical art to the symbolic musings of Austin Osman Spare (1886–1956) and the psychedelic transhumanism of Alex Gray (b.1953). Today, esoteric art also often reflects engagement with what is problematically referred to as the ‘Western esoteric tradition’, representing an imagined universal or perennial wisdom tradition, passed to elite initiates, sometimes belonging to a mystery school, such as Freemasonry, Rosicrucianism, Theosophy, Ordo Templi Orientis (OTO) or the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.11 As a result, esoteric art and esotericism in general tends to be discussed as part of, and a reaction to, a wider set of dominant intellectual, political, artistic and philosophical currents in the West, and is often positioned against narratives of secularism and disenchantment – narratives that themselves are being widely reassessed.12

In trying to establish some sort of definitional foundations, the scholar Marco Pasi has outlined four contexts in which esoteric art is created.13 First is the representation of esoteric symbols or images, second is the production of an esoteric object that can be treated as a fetishistic item, third is when the work is produced to induce a spiritual or extraordinary experience, and the fourth is when the work is created as a result of contact with spiritual entities. Pasi’s categories are useful, yet he seems to be asserting that society is broadly rational and that the power of esoteric or occult art comes primarily from operating in resistance to this overarching rationality. In many ways, this simply reifies the portrayal of a uniformly rational ‘West’, and marginal practices that sit in opposition to it. The wider story is of course much more complex, as people have shifting, multilayered and inconsistent relationships with regards to esoteric worldviews. Additionally, some esoteric works are not designed solely to produce a spiritual experience, since that spiritual experience is intended to sow the seeds of individual and social transformation. This element is a critical feature of much art inspired by esoteric principles, both past and present.

The reasons for this growing interest in esoteric art has been a source of rather broad commentary, and is likely the result of several trends developing over the past decade, and with increasing urgency since 2016. First, the interest is clearly linked to the continuing reconsideration of women’s art. The renewed focus on women’s contributions to Surrealism and a continuing reassessment of women’s role in the history of abstraction have helped to propel esoteric and occult systems of belief and practice into the spotlight, as we work to understand the formative impact of spiritualism, sacred geometry, Theosophical colour theory and Rosicrucianism on art. For af Klint, Georgiana Houghton (1814–84) FIG. 2 and Ithell Colquhoun (1906–88), for example, women’s esoteric practice was foundational to their artistic innovations, which historians are now, at least somewhat, starting to try to understand.14 It is a long-held belief that the occult practices of artists and writers were merely of symbolic import; occult themes were interesting, but not to be understood as an element of their actual operating worldview. Such ideas were often considered as a source of embarrassment, detracting from the intellectual and rational engagement with philosophical and artistic movements that scholars wished to project onto their subjects. A sad vestige of this can be seen in Jason Farago’s shockingly disparaging New York Times review of the exhibition Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897, held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 2017, in which he refers to the underpinnings of the show as ‘mystical mumbo jumbo’ and ‘Spiritualist schlock’.15

In 2022 Farago’s review makes for uncomfortable reading as the framework for appreciating the spiritual foundations of esoteric art evolves. In addition to the widespread and growing interest in women’s art, the increased globalisation of the art festival format as a space for showcasing non-Western and experimental artistic practices may also support greater validity for occult and esoteric ideas in the wider context of diverse global religiosities. As the cultural sociologist Monica Sassatelli notes, the rising emphasis on biennales as a way to expand the audiences for fine art is also creating the conditions for a renegotiation of the boundaries of fine art outside of traditionally Eurocentric models.16 This may also have the effect of opening up our historical understanding of a range of heterodox spiritualties in the West. To this point, the explicitly ethnographic gaze adopted by Massimiliano Gioni in his 2013 Venice Biennale exhibition, The Encyclopedic Palace, helped provide a comfortable distance through which to explore the esoterically motivated pieces he included in a comparative cultural framework that focused on the imaginal.17 The Encyclopedic Palace featured the visionary, enchanted and uncanny, including paintings by Aleister Crowley (1875–1947) and af Klint, personal artefacts of the esotericist Rudolph Steiner (1861–1925) and Carl Jung’s lusciously illustrated The Red Book: Liber Novus (1915–c.30), placing them in a global context of art that addressed the expression of the imagination. The exhibition was broadly conceived as a museum devoted to displays of different systems of knowledge, deliberately adopting a distanced curatorial position with regards to the material.

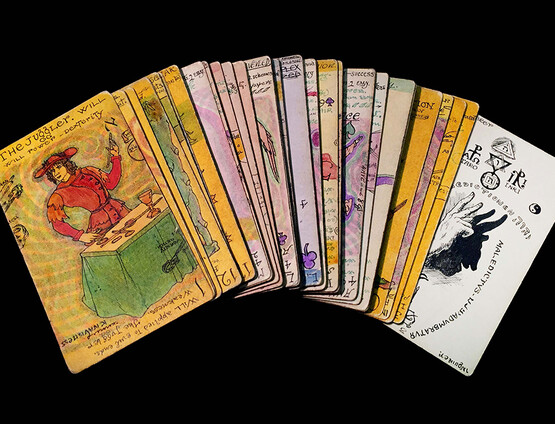

An additional factor that may support the current interest in esoteric art is a widespread and inaccurate conviction that there has been a recent surge in cultural interest in the occult and witchcraft, primarily inspired by a variety of environmental, political and economic crises.18 Indeed, many of the reports on the current trend of esoterically inspired exhibitions are driven by this claim, despite the fact that such work has spanned a variety of time periods, even those considered to be relatively stable and prosperous. While this article was in preparation, the critic J.J. Charlesworth published an extensive survey of the recent preoccupation with magic in art, chronicling many of the events, trends and artists addressed by the present author.19 However, Charlesworth situates this trend in a reactionary desire to embrace the atavistic and antimodern through magic and re-enchantment, with both artists and audiences seeking refuge from secularism and alienation. However, it appears that it is this pattern of analysis rather than the occult itself that is tied to moments of upheaval. Historically, ‘occult revivals’, such as those associated with the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, tend to be accompanied by widespread assertions that fear and instability will inspire a nominally rational culture to manage uncertainty through an embrace of divination, magic and new religious movements. Since 2016 – the year of the Brexit vote in the United Kingdom and the election of Donald Trump in the United States, two landmark events that have been considered to be socially destabilising – there have been myriad analyses of the new ‘fads’ of witchcraft, tarot cards and astrology, despite the evidence that there is actually a fairly consistent interest in these topics. The first real explosion in popularity of witchcraft in the twentieth century started in the mid-1950s and early 1960s in Britain, prior to the mix of the counterculture with any occult revival.20 Even when the waters of history are less troubled, there will always be people lacking access to resources and power, and magic has persistently been the strategy and domain of the underclasses, the marginal, the oppressed and – of course – women.

Although the history of occultism and esotericism is dominated by such large male personalities as Crowley, it has in many ways been considered a ‘feminised’ way of knowing. Historically, women have been associated with supernatural and psychic abilities, to say nothing of their association with witchcraft.21 With the exception of Freemasonry, most occult and esoteric activity happens in domestic spaces, traditionally held to be the domain of women, imaginatively captured in the bewitching and delightfully spirit-filled kitchen scenes of Carrington FIG. 3 and Varo FIG. 4. However, the academic study of esotericism, like the academic study of art, has frequently downplayed the participation and impact of women.22 In fact, esotericism is often defined by academics in such a way that women, as well as marginalised and colonised peoples, are made invisible. The study of Western esotericism has focused on a culture that is elite, white, overwhelmingly male and literate, concentrating on the primary European male theorists of Gnosticism, alchemy, Renaissance magic, Hermeticism and modern occultism.23 Some scholars of esotericism have argued that this demographic constitutes necessary and coherent defining features of the field that should not be compromised, yet these restrictive parameters exclude a lot of magic-making by a variety of peoples throughout history.24 Naturally, this impacts the emerging story of esoteric art, which we know to be greatly influenced by women’s practices, such as spiritualism and witchcraft, which are often sidelined in academic narratives about esoteric history.25 In addressing the stories and experiences of women, it is also difficult to ignore intersectional questions of class, literacy, race, embodiment and relationships to power and institutions. Although religious studies scholars have argued that artefacts and texts relating to women’s religious life and practice are frequently not available for study, this should not be mistaken for evidence of absence or lack of relevance.26 This should also sound familiar to art historians reconstructing and reasserting the importance of art made by women.

Women change how we understand esoteric practice. What may be the conception of esotericism as defined by the study of white literate men will not be what it looked like when practised by and embraced by women. For instance, magic done in domestic spaces, folk medicine, service magic, divination, witchcraft, contemporary ritual and altered states of consciousness have, until recently, been understudied by scholars of esotericism.27 However, when we change the frame and let women, practice and art lead, the frame itself changes. Carrington’s kitchen ghosts, the African American magic and mysticism in the work of Betye Saar FIG. 5, Reneé Stout’s rootworker inspired installations FIG. 6, Gertrude Abercrombie’s eerie, spectral figures FIG. 7 all capture features of women’s supernatural experience that have not figured in the male-driven histories of the occult. Similarly, when we tell the story of women’s contributions to art it disrupts the wider discursive field of art history, necessarily pushing toward greater inclusivity. The impact of af Klint on the history of abstraction FIG. 8 is clearly one such story, but the narrative changes yet again when considering the earlier mediumistic abstractions of Houghton.28 Spiritualist art, long marginalised and relegated to the categories of visionary or ‘outsider’ art, is now blurring the boundaries of dominant artistic discourses.29

Queer feminist esoteric futurism

As the 2022 Venice Biennale captured a narrative concerning women’s magic from the past, it also provided a subtle glimpse of a new, feminist reframing of magic, which is once again changing the substance of esoteric discourses. Alemani offers a curatorial rejoinder to the imagined cultural centrality of the Western, perfectly integrated ‘Man of Reason’ by embracing explicitly feminist-inspired expressions of posthumanism and hybridities. 30 The inclusion of such artists as Marguerite Humeau, Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill FIG. 9 and Sandra Mujinga FIG. 10 indicated, if not fully articulated, the shift in cultural development in wider conversations about women and esoteric thought. This caduceus-like entwinement of women’s esoteric and artistic histories provides the groundwork for situating a distinctive movement in magical culture that is evident in the work of explicitly esoterically inspired contemporary women, trans and non-binary artists. The trend is most apparent in the New Mystics, a collective of twelve artists coordinated by Alice Bucknell (b.1993), which includes Tai Shani (b.1976), Zadie Xa (b.1983) FIG. 11, Saya Woolfalk (b.1979) and others, but such theoretical and aesthetic sensibilities are also found in the work of Juliana Huxtable (b.1987) and even the musical artist Björk, most notably in her 2011 multimedia production Biophilia.31 These artists embrace magic, myth and otherworldliness but they also defy and critique the ways in which the occult and esoteric have been previously characterised. In fact, these artists might almost slip the gaze of those who take an interest in esoteric matters, for they hardly replicate the yearning for a romantic, magical past that is often a key feature of the occult aesthetic. Instead, they reject it entirely or subject it to critique. The ghosts are not ephemeral, the witches are revolutionary and the enchantment is not comforting. Importantly, these artists are decoupling occult and esoteric aesthetics from the academic stranglehold of ‘The West’, paralleling critiques of the study of esotericism from within the field and comprising vibrant, diverse and artistic voices.32

Jamie Sutcliffe’s edited collection Magic: Whitechapel Documents of Contemporary Art deftly captures the spirit of this developing occultural sensibility.33 The collection includes a wide-ranging crop of artists and thinkers from both the past and present, assembled to provide a new framework for magic and esotericism and to guide artistic practice. Sutcliffe critiques a particular view of magic, hemmed in by ideas of tradition and golden age thinking, providing a necessary departure from both popular and academic constructions of esotericism, frequently steeped in romantic, cryptic aesthetics and ideologies. In his introduction, Sutcliffe notes the current propensity for framing the present interest in the occult and esoteric as a reaction to crisis.34 He notes that this perception is cyclical, obscuring what is actually a consistent interest in esoteric practice. However, as the book demonstrates, there is no doubt that practices and orientations are responsive to context, and the artists and thinkers who are situating themselves within this critical new framework are, indeed, responding to historical and cultural challenges. Inspired by Donna Haraway, these artists are ‘staying with the trouble’, responding to the staggering conjunction of climate crisis, changing ideas about gender, the rise in authoritarian politics, economic injustice and a host of deep structural social and cultural disturbances and transformations. However, these artists are not providing artistic distractions situated in antimodernist or romantic aesthetics of enchantment, but instead formulating conceptual spaces for considering new futures, still firmly grounded in esoteric principles. But this is an esotericism that resists boundaries, linearity and form. It is occulture heavily remixed and reconceptualised to magically undo the ties that bind us.

In fact, it is the radical undoing of form, structure and linearity that lies at the esoteric heart of many of these projects that embrace hybridity, queerness, post humanism and an inspirited universe. This constructivism is itself deeply magical, suggesting that the agency of transformation is not yet lost. As Bucknell stated:

I think in the simplest of terms my interest in magic as a kind of technology stems from its ability to break apart, or break down, certain systems of thinking that have led us into [this] multi-pronged crisis […] it also proposes a speculative and open-ended way out of the mess of the present towards multiple possible futures.35

Perhaps the most critical characteristic of this movement, the one that counters the dominance of Platonic ideologies pervading most of the occult, is the rejection of essentialism, the notion that beings are delimited by immutable characteristics. In fact, in many of these works human bodies are porous, connected and often undefined. The persistent relevance of Haraway dominates the theoretical fabric of these artists, with influences ranging from the abiding Cyborg Manifesto (1985) to Staying with the Trouble (2016).36 Haraway emphasises the planetary condition of various enmeshments – with technology, non-human animals and plants – breaking down conceptual and physical essentialisms, promoting an ethos of care and mutuality, what she refers to as the entwinement that emerges from ‘tentacular thinking’.37 Haraway’s conception of ‘feminist speculative fabulation’ resounds with relevance in characterising these artists: ‘It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories’.38

Thus, science-fiction-inspired world-building becomes a key artistic enterprise. The writings of Octavia E. Butler and Ursula le Guin merge with queer theory, Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism, producing theoretical landscapes where playful approaches to myth and tradition blend with artificial intelligence; indigenous wisdoms fuse with hybrids species; and priestesses, witches and goddesses transmit the spores of psychedelic liberation. 39 Through performance and self-portraiture Huxtable presents herself as a luscious green-skinned alien, most famously in Untitled in the Rage (Nibiru Cataclysm) FIG. 12. Huxtable’s ‘Nuwaubian Princess’ persona – inspired by the posters and art created by the esoteric Afrofuturist and Black nationalist Nuwaubian Nation, blends Egyptian and UFO religiosity – providing a conceptual space for of embracing fluidity in images of her own body. The Butler-inspired utopian worlds of the Japanese-American artist Saya Woolfalk exemplify Haraway’s enmeshment, featuring plant-human hybrid beings of shifting colour and gender who gain empathy through experiencing varying realities through their changing bodies FIG. 13. Woolfalk’s rich, textured worlds incorporate African and Asian visual influences, yet she notes that her trend toward the digital helps foster idealised worlds that are ‘post-race, post gender [and] post human’.40 Both Woolfalk and Huxtable destabilise the elite construct of the ‘Western esoteric tradition’, jettisoning its underlying, insidiousness whiteness.

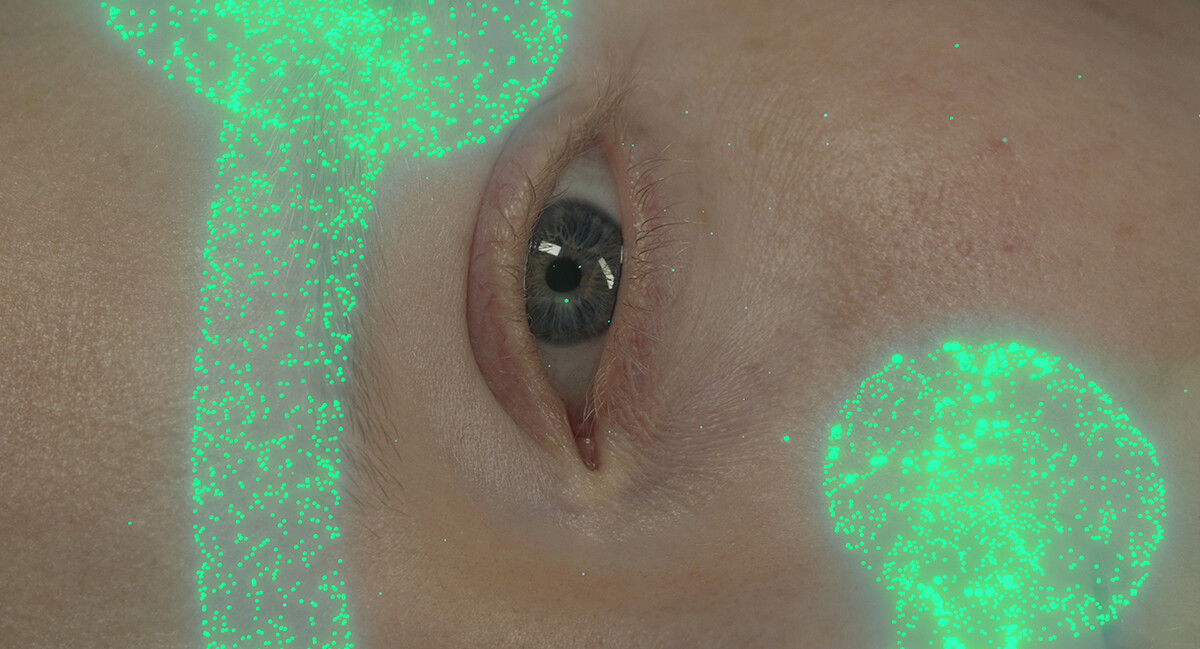

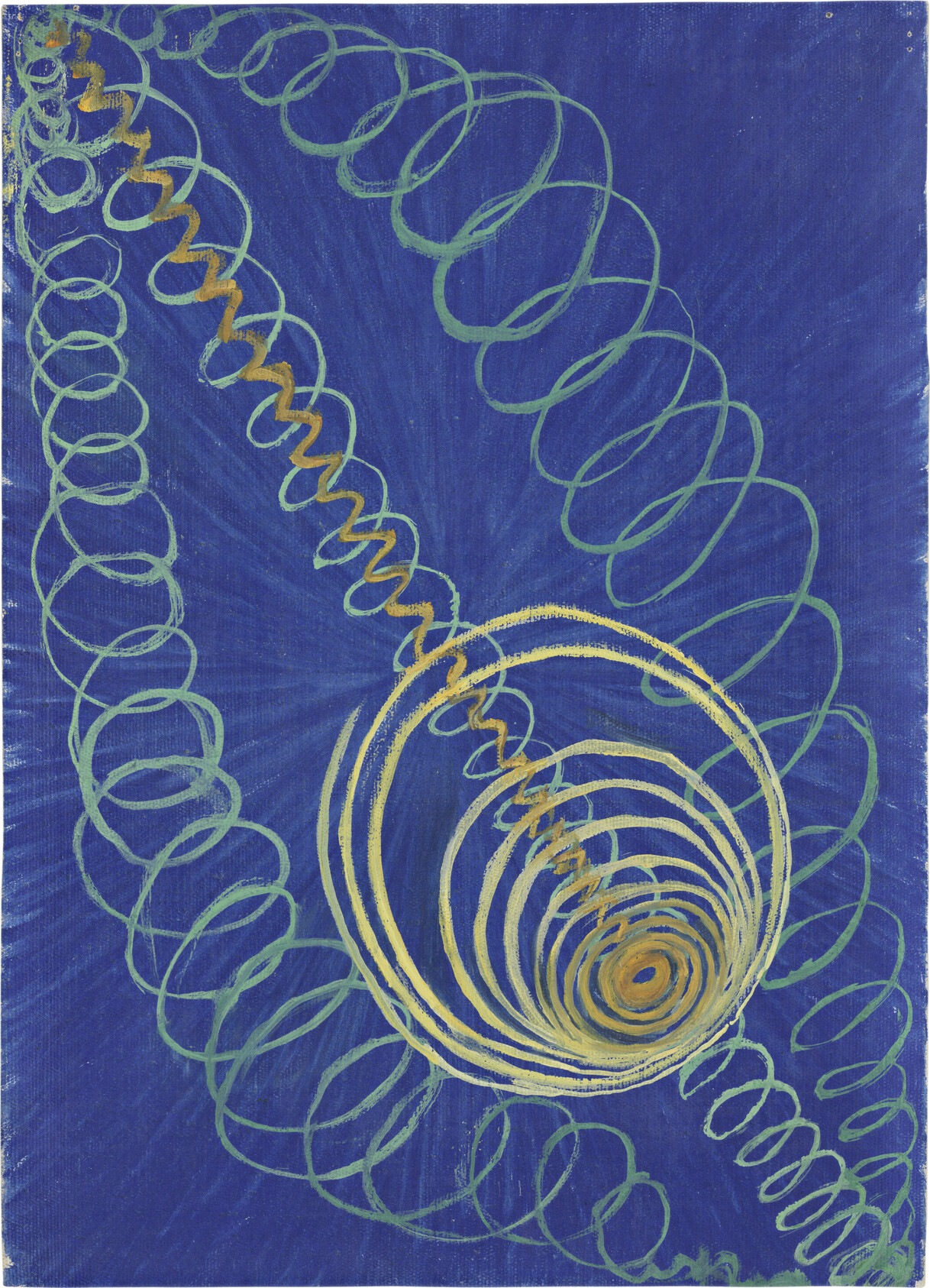

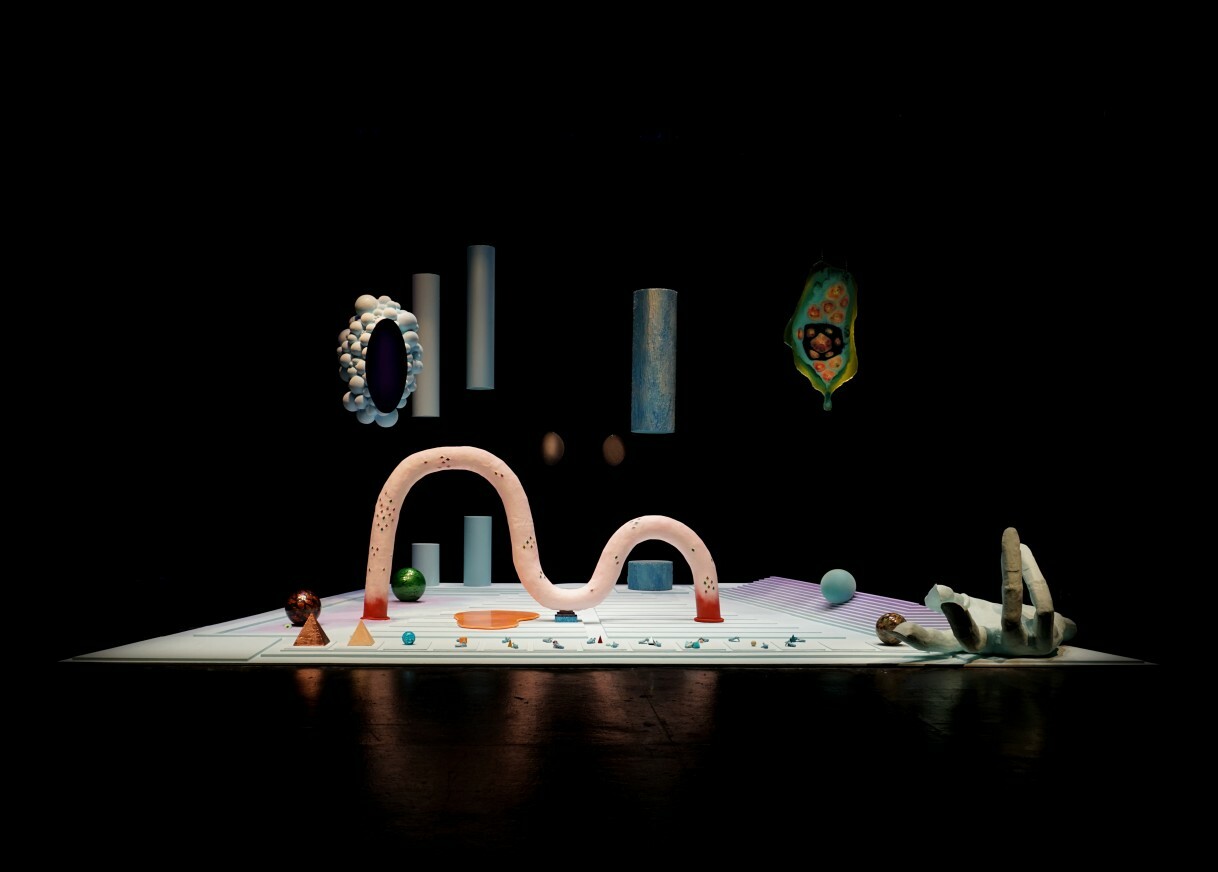

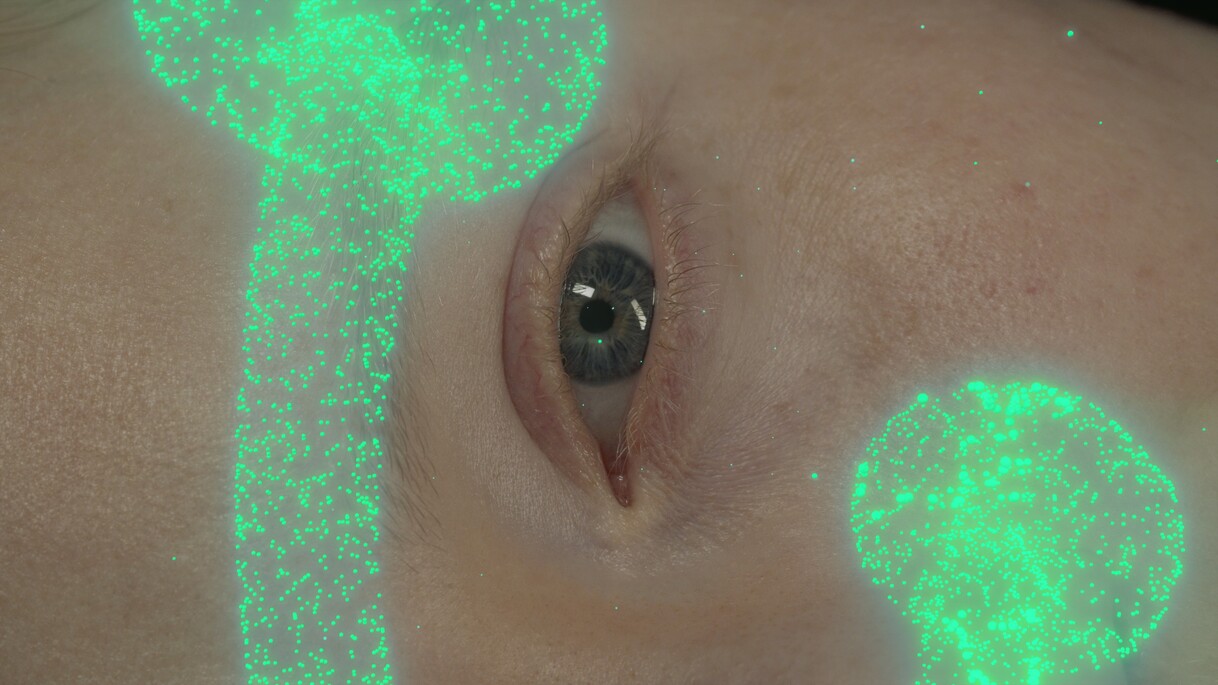

An esoteric principle embedded in many of these works is an embrace of extra dimensionality, challenging conventional perceptions of space and also linear time, echoing the early twentieth-century artistic fascination with the fourth dimension without necessarily paying direct homage to that period. During the first half of the twentieth century the fourth dimension as both an esoteric and scientific principle was embraced by Cubists, Modernists and some Surrealists as a framework for visually expressing theories about unseen planes, higher spiritual realities and a sense of the infinite. For such artists as Shani, linear time is abandoned as part of a critique of capitalist and neoliberal narratives of progress. The result is that past and future worlds are conflated, reality and the mythic exist in a multiverse where everything is possible. Shani’s DC Productions FIG. 14, a series of installations and performances inspired by Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies (1405) moves images of women through time from myth to history to autobiography and science fiction. The full exhibition text, published as Our Fatal Magic in 2019, evocatively connects women through their shared wounds and the city they inhabit, defying time, gender and any discrete sense of physicality. 41 Her later and slightly lighter project The Neon Hieroglyph FIG. 15 is a multi-genre work exploring the legendary history of hallucinogenic ergot. Here time flows effortlessly from the visions of priestesses in the Eleusinian mysteries to mid-century France to the COVID-19 pandemic. The audience is a spore, a witch, stardust, in fact all things in all times.

In the various elements that comprise The Neon Hieroglyph, the witch appears as a dimensional shapeshifter moving through time and space, breaking down oppressive social and cultural structures. In the story of women’s esoteric art, the witch is a necessarily ubiquitous figure, speaking to liminality, subjugation and the suggestion – and likely also fear – that women are uniquely placed to walk between worlds. She is an outlaw and her ability to curse and heal implicates her in the meting out of informal justice; she possesses no earthly authority but through magic she protects and is the righter of wrongs. As such, the cultural positioning of the witch as a motivator of spiritually charged activism is becoming more relevant in an era in which formal mechanisms of social care and even the general ethos of social responsibility are disintegrating. Shani’s witches are inspired by the remarkable story of the Italian island of Alicudi, where poverty-stricken residents were said to exist on a diet of ergot-contaminated bread, causing them to live in a constant visionary state, where the limits of reality were uncertain. Out of this hallucinatory world grew tales of flying women, the Maiara, who would journey to the mainland at night to steal feasts for the starving islanders – part of a complex of Italian folk traditions where witches are both bringers of gifts and also rebels against oppression. In a forthcoming book that will form part of The Neon Hieroglyph, Shani’s witch is a figure of bounty and revolution, performing incantations to the spirits of matches that will burn the system down. Shani’s two sculptural witches FIG. 16 produced as part of the material component of The Neon Hieroglyph are very much not of this plane. Their skin and hair are shades of green, like moss or algae, but shiny and supercharged. They radiate a certain ecstasy. One witch appears wild with joy and the other appears serene, hands covered in sores, possibly asleep, possibly dead, wearing the tiniest of all candles on her eyelids, suggesting the power of continual sight. These witches provide a compass toward liberation and in some way serve as guides through the radical communal ethos of the project.

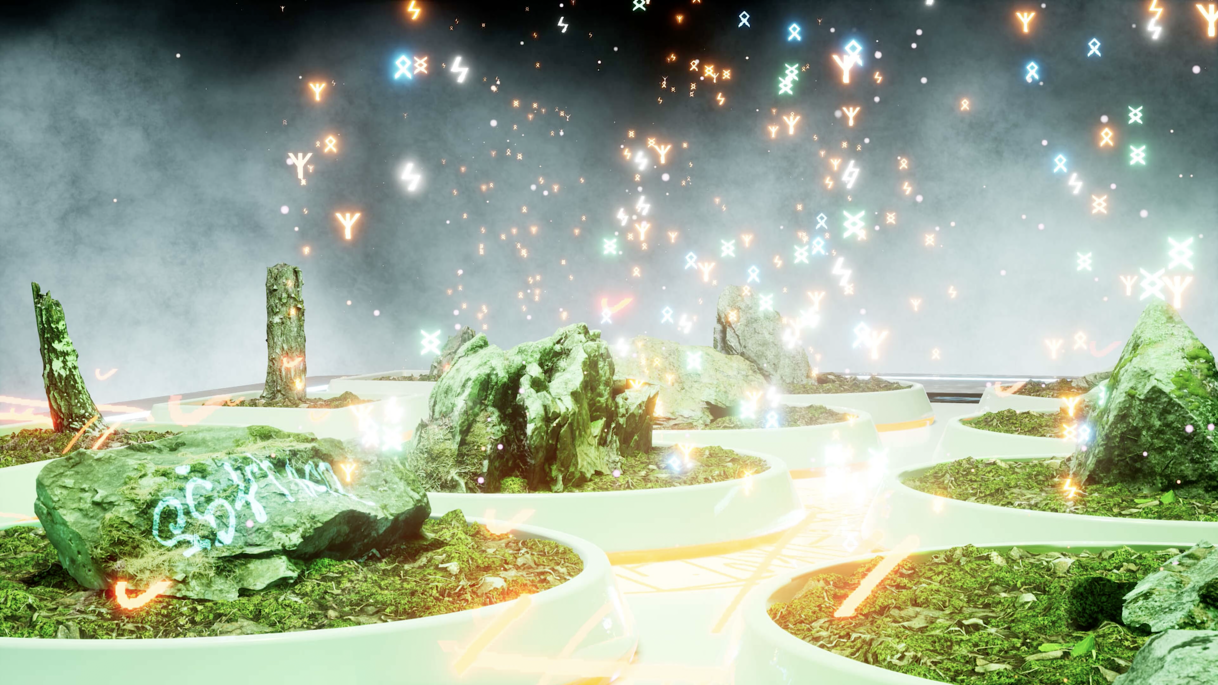

In characterising the New Mystics, Bucknell notes the importance of world-building and the propensity for these artists to work in multiple genres, using game design, AI and immersive technologies, providing the ability to create fantastic dreamlike experiences and virtual collaborative ritual, recalling chaos magicians of the 1990s, using early iterations of the internet in distributed magical workings FIG. 17.42 The New Mystics web platform incorporates an AI interface, GPT-3, a natural language text programme, which Bucknell suggests encourages polyvocality and also lends a certain uncanny, even ghostly, presence to the project as a whole. The focus on immersion also resonates with some of the earliest aims of ritual occult performance championed by the nineteenth-century Symbolists, and later embraced by such occult ritualists as Crowley and the Golden Dawn member and actor Florence Farr (1860–1917), who created theatrical ritual experiences designed not only to produce an altered state of consciousness in the audience, but also to promote personal and social transformation.43 Bucknell is explicit about the desire of the New Mystics to use the idioms of magic as a vehicle to engage with the legacy of colonialism, racial injustice and to empower the devoiced. She calls magic an ‘intersectional social process’, poised to move beyond the artistic fetishisation of symbols and cultural appropriation.44

Imagined pasts versus imagined futures

In many ways the revolutionary and collectivist sentiments of this trend are not new: radical queer witches and liberatory magical politics have always been part of the occult and countercultural landscape, yet the idea of occultism and futurism of any sort are frequently placed ideologically at odds with one another, with occultism so heavily linked with imagined pasts. However, it may be time for a new, radically retooled esoteric futurism to reassert itself. Fin-de-siècle and early twentieth-century occultism was steeped in visions of a spiritually driven and technologically advanced future, as society was still trying to figure out where the limits of science ended and magic began. This was a period when the occult and art were awash with progressive politics and inspired by the wonders of technology, when the X-ray and photography provided the scientific potential for the eventual proof of numinous dimensions, thoroughly wrapped in occult worldviews about vibrations and electromagnetism.45 Spiritualism and Theosophy were believed to offer experiences that could be subjected to empirical testing, proving that spiritual aspirations could be scientifically supported. So, while today the abstract paintings of af Klint are appealing partially because of her links with spirits and occult systems of thought, to her they were just as much indebted to scientific discourses about atoms and the deep patterns underlying the material world. Ithell Colquhoun was an animist who saw spirit running through all things FIG. 18, but she also had a sustained, lifelong interest in research about the fourth dimension, which for her explained the existence of spiritual planes that could be reliably accessed through consistent methods.

That esoteric ideas and cultures should lead to creative portrayals of new and different worlds and a radical rethink of existing and constraining social relations is also not a particularly novel concept, but it has certainly taken a back seat to visions of quaint, premodern enchantments. Italian Futurism and Russian Cosmism both fused ideologies of science and science fiction aesthetics with occult metaphysics to produce supercharged visions of the future, incorporating extra dimensions, space travel, extended life spans, telekinesis and transhumanism.46 Unfortunately, both of these examples are also politically terrifying, steeped in misogyny, hierarchies and the sorts of totalitarian projects that continually plague occult-based fantasies of social planning, which is where this particular direction of feminist esotericism becomes explicitly resistant. One explanation for this consistently regressive and traditionalist streak is that the occult is imbued with mythologies of spiritual loss and degradation, and the desire of many occultists has been to reconstruct a utopian society rooted in fictional lost worlds, such as Atlantis or Eden, when perfect humans lived in reciprocal relationships with nature and other animals. Perhaps, as in Atlantis, they had advanced spiritual technologies like universal telepathy or, as in Eden, they were genderless like God. However, for many occultists in history, only the spiritual elite were believed to have the capacity to understand this condition and strive for this idealised state. Contemporary esoteric artists are not driven by loss and longing, with mysteries only to be revealed to the initiated few; they are focused firmly on the fortunes of the collective, envisioning potentially infinite futures.

This recontextualisation of magic and esotericism is also not confined to artistic expressions. There are resonances in other cultural spaces where feminist esotericists and occult practitioners are currently challenging the received wisdom around who sets the tone for magical practice. The publisher Ignota Books, which has collaborated with both Shani and Bucknell, promotes a list that is deeply connected to the magical and the esoteric and is committed to diversity, inclusivity and creative imaginings of alternative worlds. Ignota is reshaping the magical terrain of both practitioner and audience, inventively blending occultism with indigenous wisdoms, psychedelic culture, ecomysticism and AI. The philosopher and chaos magician Patricia MacCormack (b.1973) articulates the radical potential and inherent queerness of chaos magic, identifying it as a potential tactic for a critical undoing of systems of oppression and potentially eliminating anthropocentrism, working toward an ‘ahuman future’. In a sense, MacCormack is restoring chaos magic, a magical subculture known for its contempt for hierarchies and a rejection of centralised spiritual truths, back to its revolutionary punk-inspired roots of the 1970s and 1980s. MacCormack is definitely promoting a ‘DIY occulture’ that is anticapitalist, creative and inspired.

It is worth noting that the collection of artists under discussion here is only one development within a growing list of women artists currently expanding the use of occult and esoteric idioms in thoughtful, novel and diverse directions. In a time of persistent crisis, where desirable or even viable models of the future are in short supply, the invitation to imagine differently and collectively is both radical and welcome. Magic is being recast as a way to inspire wonder and to consider the relationship between humanity and the planetary condition. These artists are also providing data points for the shifting scholarly conversations around esotericism and the occult, demonstrating a persistent diversity of thought and practice, dismantling outmoded and constraining categories, and once again expanding our horizons.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Alice Bucknell for generously reviewing the initial concepts of this essay, and Jamie Sutcliffe and Phil Hine for engaging her on the magical state of the world.