Bontaro Dokuyama’s ‘Even After 1,000 Years’

by Jason Waite • November 2023 • Journal article

Introduction

There have been a number of artistic responses to the triple reactor meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), which began on 11th March 2011. These include an ongoing, largely invisible exhibition in the Fukushima exclusion zone by the collective Don’t Follow the Wind; Les Nucléaires et les Choses (2019), a video installation by Hikaru Fujii (b.1976) that examines the collections and documents left behind in archives and museums in what has been designated the ‘difficult-to-return zones’; and the work of the artist Kota Takeuchi (b.1982), who acquired a job as a clean-up labourer at the plant and produced a number of projects on the area’s history and its changing present.1 However, there are only a handful of artists born and raised in Fukushima who have exhibited outside of the area, such as the documentary photographer Shuji Akagi (b.1967) and the painter Miki Momma (b.1981). This intrinsic perspective is important, as the sociologist Hiroshi Kainuma (who was born in Iwaki, Fukushima) states: ‘there is always a perception gap between those who look out from and those who look into any given place’.2

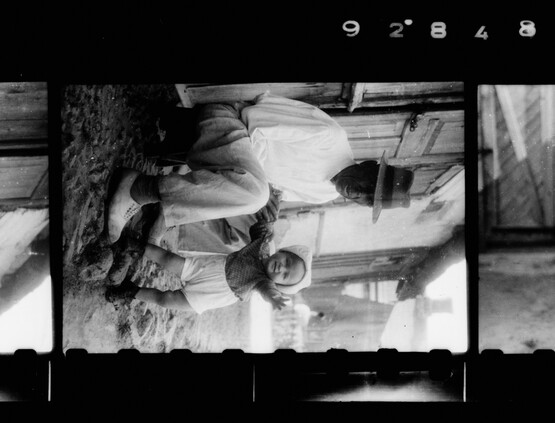

This article addresses the practice of the Fukushima-born artist Bontaro Dokuyama (b.1984), who traces experiences of the disaster in his work. In Over There FIG. 1, for example, he explored the mass displacement of people from their homes, working with residents living in temporary housing, who designed masks from cut up pages of a local newspaper. The residents – most of whom were elderly – each donned their mask and were filmed and photographed by the artist pointing in the direction of their home town. In LInCCAi-chan FIG. 2, the artist examined the economies that were bolstered in the wake of the disaster, in particular the sex shops of Iwaki. Striking a parallel with the commodification of people, Dokuyama visited the factory of a popular children’s doll called Licca-chan, adopting her as a tool for his own healing.3 In the 4th branch, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry FIG. 3 FIG. 4, the artist collaborated with the anti-nuclear protest movement that had long-been established in tents outside of the the government building in Kasumigaseki. Dokuyama’s work helps to shed light on the temporality of the nuclear disaster, as experienced by an artist whose knowledge of the land traverses the period before and the contaminated fallout afterwards. This article focuses on the documented performance Even After 1,000 Years (2015), and on the way it explores the multiple temporalities at work in the low-level irradiated landscape surrounding the nuclear power plant.

The space–time matrix of contamination is defined by the invisible presence of radiation on the land. Due to differing radioactive half-lives – the length of time it takes for half the radioactive atoms of a radionuclide to decay – this is durational in nature. Analysing Even After 1,000 Years, which was made four years after the nuclear accident, this article will explore the temporal schism of the disaster through the lives of local residents. As of 2023 many locals surrounding the plant have been forcibly evacuated, or – as is the case with Dokuyama’s family – evacuated for a short period, before returning to their homes in the low-level irradiated landscape, which is outside of the mandatory evacuation zone. There have been multiple reports on the views of local residents who used to live in areas surrounding the power station, who continue to be displaced by the fallout or who have returned to irradiated areas, with some later surveys shifting towards an assessment of what it means to have lived in the area in the ten years since the disaster.4 This article will demonstrate that Even After 1,000 Years helps to convey the residents’ sentiment in the period before and immediately after the disaster. The work also addresses one of the most important ‘invisible’ effects of the nuclear disaster on the inhabitants: the mental health damage among the local population, one of its most enduring legacies.

Among the artists who have responded to the nuclear disaster, Dokuyama has the unique perspective of a deeper relationship with the land. The effects of the disaster are not abstract to him, as his family lives constantly with the potential threat of radiation. The present author argues that this has produced an increased sensitivity to the landscape, and its relationship to the body through the recognition of its capacity to cause damage. Thus, Dokuyama’s work on Fukushima has a distinctive character that meshes a longer temporality with the landscape and the body to repair how the lived environment is understood.

The disaster was also formative to Dokuyama’s decision to become an artist. Although he grew up in proximity to the nuclear power plant, he was living in Tokyo in 2011, working as an interior designer. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, he felt that the voices of the inhabitants of Fukushima were not being heard in the media and their experiences were under-represented in wider culture. Reflecting on the communicative capacity of his occupation at that time, Dokuyama noted that ‘a building interior cannot convey the voices of the Fukushima people to the outside’, and decided to quit his job to become an artist.5 It is clear from his statement that even though he was based in Tokyo, he strongly identified with his hometown and its residents. Moreover, his turn to a different kind of creative practice was predicated on his belief in the capacity of art to convey the experience of what it means to be from Fukushima.

Given the lasting nature of the nuclear disaster, the aftermath of which is still ongoing, for Dokuyama, art could not be undertaken in a casual or temporary way. He committed himself to becoming an artist full-time and began studying Buddhist and still-life painting. In 2013 he joined the alternative art school Bigakkō, Tokyo, where he studied under Ryuta Ushiro of the Chim↑Pom collective. Dokuyama became part of Tensai High School!!!!, a group of Ushiro’s students, along with the artist duo Kyun-Chome. It was here that he experimented with expanded forms of artmaking, such as performance, video and installation, which have come to be central to his practice. Dokuyama’s continuing commitment to art also speaks to the importance of maintaining the position of being an artist in order to communicate the changing effects of the radioactive fallout over time. His desire to share the voices and experiences of the people from Fukushima has taken shape both in his collaborations with fellow residents and through performance that involves the deployment of his own body and voice, as in the case of Even After 1,000 Years.

Is this sky the real sky?

The documented performance Even After 1,000 Years took place not far from Dokuyama’s family home in Fukushima, atop the dormant volcano of Mount Adatara. It is a site made famous by the avant-garde artist Chieko Naganuma (1886–1938), who was also born nearby. On the mountain apex is a carved wooden post with the inscription ‘This sky is the real sky’, which is attributed to her in a poem written in 1928 by her husband, Kōtarō Takamura (1883–1956). In the performance, Dokuyama reads the inscription aloud in the pouring rain, declaring that this is indeed the real sky FIG. 5 and proclaiming that all other skies are fake. He then vacillates, asking Naganuma whether this is really the true sky that she loved. The title of the work comes from a line in another poem by Takamura, about a posthumous sculpture he made of Naganuma, which is situated in Tohoku, at the edge of Lake Towada. The poem speaks of the conditions that the sculpture must endure, being exposed to the open air and the harsh northern elements.

On Mount Adatara low-level radiation from the nuclear fallout prevails. Fukushima has a long history of extractivism and accidents prior to the 2011 meltdown, and Mount Adatara is no exception. The summit crater was the site of a large-scale sulphur mine and in 1900 an eruption killed over eighty workers.6 In Even After 1,000 Years the mountaintop is shown littered with broken rocks, among which Dokuyama stands. It is unclear whether this debris is related to the eruption however; given the context of the site, it is not difficult to interpret the rocks as an evocation of the history of extractivism in Fukushima. Thus, one can understand the setting as rife with mining collateral and low-level radiation: two by-products of the catastrophic condition in Fukushima.

Much has been written about the cultural and political significance of landscape. For the purposes of this article, W.J.T. Mitchell’s writings are most instructive, in his focus on not just what landscape reveals but also what it obscures. He understands landscape not as a noun but as a verb akin to a ‘cultural practice’.7 For Mitchell a landscape is more than a signifier of power relations. Rather, he positions it as a ‘cultural media’ with the role of naturalising ‘cultural and social construction’, which consequently produces an ‘artificial world’ that is received as ‘given’.8 Moreover, for Mitchell, the landscape always exists in relation to the human figure; whether the figure is present in it or viewing it from afar, the landscape is an anthropogenic formation.9 And yet, it often obscures this reality by appearing as it always has. Applying this understanding, what can one see on Mount Adatara in Dokuyama’s work? The site has clear evidence of human intervention in the form of a large wooden marker. However, the trees, grass and shrubs that surround the clearing are dwarfed by the artist and the marker FIG. 6. It is not clear whether this constitutes a higher altitude wilderness of low-level growth or whether the foliage is indeed smaller as the result of recent growth in wake of human-caused destruction. This ambiguity can be understood as a substantiation of Mitchell’s description of landscape as a cloaking mechanism for the history and present of a place.

Dokuyama’s performance questions whether the surrounding landscape is what it appears to be. In the opening line of Takamura’s poem, Chieko says ‘there’s no sky in Tokyo’, instead she wants ‘to see the real sky’, the blue sky ‘high above Mount Adatara’.10 Takamura titled the poem ‘Talking like a child’, which appears to allude to a bemusement or bewilderment at his wife’s statement, delivered while looking up at the sky in Tokyo. At the same time, the poem was written in the early twentieth century, when the burgeoning metropolis of Tokyo, the centre of extractivism, had one of the most polluted atmospheres on earth. The city was ensconced in grey skies, caused by the plentiful smokestacks of heavy industry.11 The sharp contrast of this dichotomy – between the industrially choked city sky and the imagined idyllic rural atmosphere – might not have been so evident to the Tokyo-born Takamura. These factories were burning coal, much of which would have come from Fukushima on the new railways. This accelerated not only the extraction of resources but also the arrival of people, including Naganuma, who took the train in 1920 as part of this early migration. Almost a hundred years later, Dokuyama followed in her footsteps, continuing the migration of the prefectures’ youth to the metropolis.

The contrast of skies presented in Takamura’s poem is contested in Dokuyama’s performance, in part due to the stormy conditions. Instead of undertaking his performance on a clear day with a view of the surrounding area, Dokuyama places himself in the midst of a rainstorm. Footage of the artist, as he struggles to complete the work, complicates any nostalgic view of an idyllic environment. It is his figure in the storm that not only disrupts the site, but also, the present author contends, plays an important role in gesturing towards the new conditions of recent irradiation of the landscape, which is pervasive but invisible. Dokuyama’s performance sets up a parallel between the historical, polluted skies of Tokyo and the present-day one over Mount Adatara. Thus, the artist’s questioning of the sky brings the nuclear fallout to the foreground.

By calling into question the ‘realness’ of the site, and highlighting its cultural binds with Tokyo through the figure of Naganuma, Dokuyama undoes the obscuring effects that Mitchell sees as intrinsic to landscape. As such, the landscape in Dokuyama’s work is not just seen through the present, but also through another’s past relationship to it. This helps to break down the presumption that the landscape, in the words of Mitchell, is ‘given’.12 This dual temporality opens the possibility of the site having been different in the past. In this way, it not only refracts time but also space. By evoking early industrial Tokyo and overlaying it on the volcano, Dokuyama demonstrates the deep historical relationship between the two and how they have affected one another: firstly, in connection to the mining industry, and secondly, from the nuclear fallout after the TEPCO plant disaster, both part of extractivist industries to service Tokyo’s development. This relationship between the city of Tokyo and the landscape of Fukushima is also part of Dokuyama’s life and artistic identity.

In 2019 Dokuyama created a follow-up, companion work to Even After 1,000 Years, titled Innocent Tale of the Sky FIG. 7. Here, an actor yells up to the sky in Tokyo, rather than in the rural landscape of Fukushima. Filmed on various construction sites for the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games, it shows a man pacing in front of cranes and lorries transporting building materials. The man is agitated, shouting angrily, with evident irony: ‘Could you build me more buildings?’ and ‘I want to see the sky full!’. Both documented performances were exhibited in the group show Plans for TOKYO 2019 at Gallery aM, Musashino Art University, continuing Dokyuama’s interest in the connection between the very different sites of Tokyo and Fukushima.

Low-level radiation

While studying art at Bigakkō, Dokuyama met the artist Sachiko Kazama (b.1972), who decided that Dokuyama’s birth name was too ordinary – not fit for an artist – and so gave him his present nom d’artiste.13 Dokuyama means ‘poison mountain’, a reference to the fact that it was the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima that propelled Dokuyama to become an artist. The performance atop Mount Adatara can be seen as him embodying and enacting this new identity. The name can also be seen as a reference to the contaminated landscape in the performance. The radioactivity in the area – caused by fellow humans – is a burden that he carries with this moniker. Yet at the same time, the name also points to the geological figure of the mountain. There is, therefore, a paradox in the name Dokuyama, which signifies both the contamination and the land, but does not figure the artist’s relation to either. Rather, the ‘poison mountain’ can be read as the ground on which he and his practice struggle.

However, this was not just a symbolic enactment of his artistic identity – his presence also embodies the ‘poison’ of low-level radiation on the mountain. The performance on Mounta Adatara has the potential to leave traces by altering his DNA. Stochastic effects are the possible outcome of any radiation exposure, but although there have been studies that show the increase in certain types of cancer caused by low-level radiation, a recent review on the effects of the Fukushima disaster by the United National Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation found that it would be difficult to discern a population-wide impact as a result of the low-level radiation experienced in the area.14 Therefore, while the stochastic effect is omnipresent, it is doubtful that there would be health impacts for Dokuyama, especially from a short exposure. Yet, by situating his own body in the prefecture’s historical location, the performance highlights the potential risks for himself and his family.

Being in low-level radiation every day produces the possibility – albeit remote – of one photon of energy from the radionuclide altering a cell, which later could cause a cancerous growth afflicting the body or even a genetic alteration with effects that can span generations. This threat occurs every moment inside an irradiated landscape and, in the present author’s experience, can change the perception of time.15 The self-awareness of being in this location can engender a nebulous anxiety, as it is not possible to see the physical danger. This can induce a hypersensitivity to time, wherein a short period feels much longer. In addition – as one second might have repercussions that emerge years, or even decades, later – there is not a clear understanding of the causality at work. This can evoke a sensation of non-linear, elastic time. Over long periods, these sensations can become commonplace, as one returns to the same places and leaves with no obvious effects. Thus, the impossibility of knowing the exact consequences from being in the low-level irradiated area can, paradoxically, normalise the experience of these conditions. The threat is parallax in nature: in the immediacy of exposure – although its effects might not become apparent at once – and the long half-lives of the radionuclides, which ensures the landscape will be irradiated for centuries, or even millennia. It is this temporal dilemma that Dokuyama and his family inhabit.

In his performance, Dokuyama utilises the relationship between his own body and the weather as a metaphor for the invisible radiation enveloping the landscape. Through this, he not only underscores the present contaminated state of the mountain and the surrounding region but also helps to bring us closer to understanding the experience of living there. His body, standing on the mountain drenched in the rain, symbolises the radionuclides that drench the area and its inhabitants in low-level radiation. It can, therefore, be understood that Dokuyama’s question is whether this contemporary atmosphere replete with radionuclides is indeed the ‘real sky’. Has the irradiated atmosphere of Fukushima transitioned the idyllic mountain in Naganuma’s poem into an unreal landscape of nuclear aftermath? If this is the case, then how does the artist convey the experience of inhabiting this new landscape?

Weathering deep time

The radioactive elements present in the landscape from the nuclear disaster range from iodine-131 (with a half-life of around eight days) to plutonium-239 (with a half-life of approximately 24,100 years). The most prevalent radioactive isotope in the region is caesium-137, with a half-life of just over thirty years. The title of Dokuyama’s performance, Even After 1,000 Years, can perhaps be interpreted as an allusion to the temporalities of deep time that the nuclear disaster evokes. This concept incorporates vastly larger scales of time that extend beyond humanity and also includes the social, political and technological entanglement of humans as a presence that has exerted a planetary force. Appealing to deep time might signify Dokuyama’s emotional relationship to the temporal as it was in 2015, four years after the disaster, with no indication of an end point. This sense of exhaustion from enduring the massive upheaval of the Daiichi Nuclear Power Station disaster, and the subsequent years of navigating the uncertainty of living among nuclear fallout, would certainly take its toll. Indeed, the temporalities of some of the radionuclides mean they will persist for an epic duration, spanning generations.

In adopting a line from the poem by Takamura as the title of his work, Dokuyama further overlaps the life of Naganuma and her sculptural effigy, which carries forth her memory for future generations. Thus, it can be seen as not only a reference to a longer temporality, but also what it might mean to endure long-term hardship. While Even After 1,000 Years gestures to an extensive timespan, it also alludes to the resilience of Fukushima and its inhabitants and the collective concern that they may be coexisting with radiation for millennia to come.

In the performance, the vulnerability of Dokuyama’s body is emphasised by his casual country attire, sporting a T-shirt emblazoned with an image of Mount Adatara, shorts and sandals, so that he remains largely exposed to the elements. The artist struggles with the rain, coughing, squinting and rubbing his face, as he attempts to talk through the onslaught. Highlighting the difficulty and its emotional toll, the artist’s physical struggle with the elements can extend the affective sensation to the viewer. This partakes in what Sara Ahmed has called the ‘contingency of pain’, whereby, seeing a distressed body, one connects to it and the site where the struggle occurs.16 She describes this response as an alignment between the observer, the struggling body and the site of the action. In the context of his performance, therefore, it is Dokuyama’s very real struggle that brings the location closer to the viewer, traversing geography and experience.

Dokuyama breaks down the remoteness and alienation of the durational struggle of coexisting in low-level contamination by utilising one set of environmental conditions to stand in for another: a rainstorm for low-level radioactivity. In doing so, the artist can physically demonstrate a struggle with the elements acted out in real time. The deluge of the rain is overwhelming, covering his body and inundating his mouth to the point where he cannot speak, and has to halt to spit out the water. This halting endurance can provide a glimpse into the true experience of the artist and his family in the longue durée of nuclear disaster.

Schizophrenic temporality

The complex experiences relating to living among nuclear fallout has also contributed to mental illness in the area. Even before the events of 11th March 2011, studies showed that Fukushima residents often grappled with mental illness, but after the disaster this was exacerbated.17 In addition to a high rate of suicide, there have been reports of depression, PTSD, chronic anxiety and socio-psychological issues, all of which are prevalent among those displaced, as well as residents who chose to remain in the surrounding area.18 Particularly challenging for mental well-being has been the urgency of the contamination coupled with the long duration of its existence, along with the forced separation of residents from their homes. These more ‘invisible’ effects have also accounted for a number of deaths attributed directly to the nuclear disaster, demonstrating its multidimensional impact.19

As demonstrated by the Chernobyl disaster, which started in 1986, schizophrenia spectrum disorders can also develop in accident survivors.20 Dokuyama highlights this potential repercussion of the Fukushima nuclear disaster through the performance’s symbolic location. Mount Adatara is site bound together with Naganuma – both through her words, recorded in Takamura’s poetry, and the wooden marker now erected there – but, for many, Naganuma herself is inextricable from her mental illness. Takamura’s collection Chieko’s Sky (1941) charts their marriage, as well as her diagnosis of schizophrenia, for which she was hospitalised in 1935 until her death three years later, from tuberculosis, at the age of fifty-two. In recalling Naganuma’s condition, Dokuyama evokes the distorted sense of time that it can engender. The critical theorist Fredric Jameson – through a reading of Jacques Lacan – has written about schizophrenia as a breakdown between the signifier and signified, which undoes the temporal unity of understanding:

If we are unable to unify the past, present, and future of the sentence, then we are similarly unable to unify the past, present, and future of our own biographical experience or psychic life. With the breakdown of the signifying chain, therefore, the schizophrenic is reduced to an experience of pure material signifiers, or, in other words, a series of pure and unrelated presents in time.21

Jameson argues that the temporal experience of schizophrenia is one of eternal and fragmented presents. Because there is no past and no expectation of a future, the perception of the present world comes with a ‘heightened intensity, bearing a mysterious charge of affect’.22 This can certainly be applied to Dokuyama’s performance: a man standing in the rain questioning whether this is the ‘true sky’. Perhaps it is a schizophrenic intensity that Dokuyama manifests through the immanence of his struggle with the rain.

Conclusion

The disorientation of time that low-level radiation can cause is central to Dokuyama’s work. Even After 1,000 Years effectively conveys the multiple temporalities of nuclear fallout: the long half-lives of radionuclides, the pervasive threat to the body in every moment and the potential changes to human DNA, which could take years to reveal themselves. The artist’s work is situated in this entanglement between the past landscape and present contaminated environment, between deep time and the single moment that could affect human and non-human life. Instead of staying away from the area after the disaster, Dokuyama returned again and again. The work dwells in this landscape, not simply to memorialise it or question its changes, but arguably as a reparative act. Perhaps he set out to rebuild his relationship to the changed land and to express – for himself and for those of us outside of the area – that it is more than a terrain of disaster.

This repair is tangible for Dokuyama and his family, who continue to live in the area. In their case, low-level radiation is not a dislocating force but rather a condition that must be accommodated. This is not to undermine its potential threat, but rather a heuristic approach to living in such an environment, which continues to be a daily reality for those in the area. What does this new assemblage of landscape and environment mean for our future entanglement of life on this planet?

.jpg?ixlib=rb-0.3.5&ixid=eyJhcHBfaWQiOjEyMDd9&s=3566466d76117e29ffb4160a639748fb&auto=format&fit=crop&w=1502&q=80)