The sculpture of Phyllida Barlow FIG.1, who died on 12th March 2023 at the age of seventy-eight, is obstructive and disruptive. It gets in your way, insists on having its own way. As you negotiate it, it works itself into your imagination, where it will stay, ready to return when you least expect it. In 2015 I was lucky enough to work with Phyllida on the exhibition set at the Fruitmarket, Edinburgh. The exhibition was dominated by untitled: blockade FIG.2, a vast sculpture that loomed impossibly large in the upper gallery, filling it almost entirely, so that all you could do was edge your way around it as you tried to work out what it was. The sculpture began life as a hasty scribble, which Phyllida drew to illustrate what she considered unique to the Fruitmarket: that, as a visitor comes up the stairs, they enter the upper gallery with their back turned, the space behind them rather than in front. She said, ‘I was trying to grab that idea in some way […] I’m not good at ideas – the minute an idea starts to take hold it dissolves into nothingness. And into that nothingness, I put the act of making’.1 The sculpture Phyllida made – the insistent, enormous thing that she put into the nothingness – haunts the Fruitmarket still.

Phyllida’s sudden and unexpected death has shaken the art world. Not only one of our finest contemporary artists, she was also one of the best teachers, with generation after generation of artists learning from her how to look at, make and think about sculpture. Her first exhibition was Young Contemporaries at the Institute of Contemporary Art, London, in 1965; her last was Hurly-Burly at Gagosian, London (19th January–4th March 2023), a collaboration with friends and co-conspirators Alison Wilding (b.1948) and Rachel Whiteread (b.1963), whom she had taught (Whiteread) and taught with (Wilding). In 2007 she won the Paul Hamlyn Foundation Awards for Artists, which boosted her confidence as an artist, and as she retired from teaching, her career gained momentum. Her two-person exhibition with Nairy Baghramian (b.1971) at the Serpentine, London, in 2010, led Iwan Wirth to her studio and subsequent representation by Hauser & Wirth brought support, opportunity and fame, with show after show of ever larger and more brilliant work. She made dock FIG.3 for the Tate Britain Duveen Commission in 2014 and in 2017 she represented Great Britain at the Venice Biennale FIG.4 FIG.5. In 2018 she made quarry FIG.6 for Jupiter Artland, Edinburgh, her first permanent outdoor work. She was a Royal Academician, a Dame and in 2022 she won the prestigious Kurt Schwitters Prize. She was the most generous of artists, who spoke and wrote about her own and others’ work with unrivalled acuity and clarity.

Phyllida had what she described as a conventional training, at Chelsea College of Arts and the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the 1960s. Her teachers taught her clay modelling, casting, plaster modelling, armature construction and assemblage with metal and wood. She taught herself what to do with these skills – how to ‘put something in the way of nothing’.2 If making was how she thought, then looking was her initiating impulse, which was also one of the principal things that she taught artists, curators and audiences. My own initiation into her process began when she pointed to a red fluffy jumper on a chair in her kitchen and asked me what I saw when I looked at it. I thought I was on safe ground: a red jumper. What she saw, she said, was not a jumper but an abstract red softness. This was what she was trying to get her work to do: to switch off the part of our brains that made things make sense and let the materials and the colours make their own meaning.

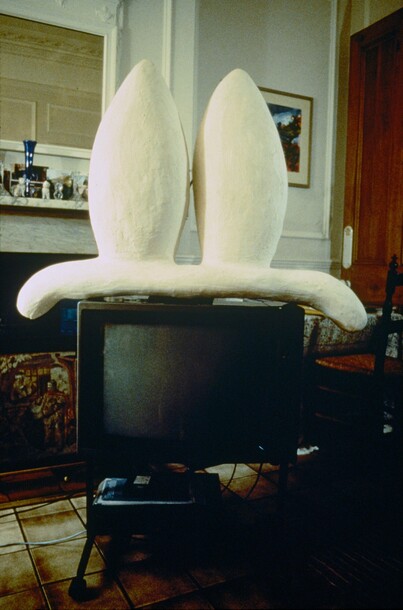

I once heard the writer Patrick Ness say that for him, a writer is someone who writes anyway, they do not wait for the perfect situation. They may lack time, money or space, but they write anyway. This is how I think of Phyllida. In the 1980s and early 1990s – a time marked by ‘a lot of teaching and a lot of parenting’ – she worked at home, producing work even when there seemed little public purpose to it.3 Her Objects for… series from the 1990s, which were made to sit on the ironing board, the piano or the television FIG.7, embody her interest in what she termed the quiet heroism of the invisible artist. In 2017, in conversation with the artist Jacqueline Donachie (b.1969), she remarked:

There has never been the necessity for the work to have a destination, or even an audience, although that has changed somewhat over the last ten years. […] I think [of] the artist who may have a studio of unseen work. I think it’s contributing to a whole sense of culture and a sense of the value of culture that somebody has given their life to it. […] There is a contribution being made even though the only transaction is between the thing that’s produced and the person who has produced it, because now there is so much art being made and so much hunger for it on many levels that it has morphed into this anthropological condition of how do we value it? How do we show it? Who is in charge of how it is shown? How does the artist fit into all of that and does the artist even call themselves an artist? Is it necessary for art to be able to define its purpose? I don’t think so because I see art as evidence, that someone has been alive, or is alive.4

The idea of sculpture as evidence that someone has lived – although heart-breaking now – cuts to the core of Phyllida’s endeavour. And we cannot infer from the value that she placed on solitary making that she did not care about the audience; her work is innately generous, making space for us as we negotiate our way round it. She valued immediacy, her sculptures presenting not as relics of activity carried out in the studio – although they are, of course, each with a process of drawing, maquette-making and redrawing built into them – but rather as present-tense things that work themselves out with you as you experience them. She wanted to make sculpture that retains the vitality of the accidental sculptures that make themselves in the street if you pay attention when walking along or looking out of the window. Then she wanted to know what that sculpture could do. The curiosity embedded in her works – the way they get in your way, make you look up, down and round – keeps them, and her, in the present tense of the encounter. ‘Are they coming or are they going? That’s my feeling about sculpture, and also maybe about our environments. Are things on their way out or their way in, and how do we know the difference?’.5

The last encounters I had with Phyllida were in Scotland in late 2022: she was on characteristically brilliant and insightful form in public, in conversation with the artist Daniel Silver (b.1972) for his exhibition Looking at the Fruitmarket; and equally so in private, when we were looking together at quarry at Jupiter Artland. It is hard not to give her the last word, when her words on sculpture were so inspirational and, perhaps more importantly, so useful. Of the Fruitmarket, although it could just as easily have referred to Jupiter Artland, she said: ‘here we are in a place which provides the encounter and allows you to get close to these things. And it is an extraordinary experience because you’re up close to something which shows the residue of a human act and it’s up to you to then make that encounter work on your behalf. You have to. It isn’t a passive experience. It’s active. And that’s what for me sculpture is’.6