We, a part of them: Laura Anderson Barbata and the disassembly of border regimes

by Madeline Murphy Turner

by Daniel Culpan

Reviews /

Exhibition

• 06.10.2021

If COVID-19 has robbed us of our complacency, it has also raised possibilities. ‘Our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to “normality”, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture’, the writer-activist Arundhati Roy wrote in April 2020.1 ‘But the rupture exists. And in the midst of this terrible despair, it offers us a chance to rethink the doomsday machine we have built for ourselves’.2 The group exhibition Portals, which was organised in response to Roy’s article, features fifty-nine artists who work in a range of media. Including fifteen new commissions, the exhibition documents life both before the pandemic and in its wake. It is a sprawling attempt to reflect on this rupture, while resisting the seduction of glib answers. A collaboration between the non-profit organisation NEON, Athens, and the Hellenic Parliament, Portals embodies the very pluralism and interconnectedness that it seeks to explore.

The exhibition is housed in the former Public Tobacco Factory, Athens, which has been repurposed into a labyrinthine space of doorless rooms and multiple mezzanines. The vast space is structured around a central atrium, which opens on to a series of sparse, industrial rooms. Leading from the entrance, the main corridor includes several works that explore language as both connector and contaminant. In Words Come From Ears (2018) by Shilpa Gupta (b.1976), a split-flap display transmits gnomic messages: ‘unbeing’; ‘unplace’; ‘unhomed’. The board’s frantic blur suggests the melancholy of transition, a between-state in which arriving somewhere new demands leaving somewhere else behind. In a year that has seen language politically instrumentalised and coarsened, the work PM 2020 FIG.1 by Teresa Margolles (b.1963) shows the degrading operations of a round-the-clock media babel. A collage of numerous reproductions of a Mexican newspaper’s front page, it creates a deafening wall of sleaze and distraction in which truth disappears into banality. The centrepiece of the first room is the forty-channel film installation Küba FIG.2 by the Turkish artist Kutluğ Ataman (b.1961). Television sets are lined up on pieces of old furniture, each facing an empty chair to create a present absence. The footage shows residents of the Küba ghetto in Istanbul bearing witness to their experience: an elderly woman in a headscarf discusses leaving her husband; a young man admits to stealing in order to survive. With its endless screens, the installation encourages us to question what we choose to look at and what we are permitted to see.

The starkness of Our Ideas #2 FIG.3 by the American artist Adam Pendleton (b.1984) – a series of black-and-white silkscreen prints depicting African tribal masks, primitivist motifs and emblems of colonialist legacies – is amplified by the impersonal atmosphere of the first room, with its grid-like windows and exposed concrete. Here, Pendleton questions how representation skews reality and what role our cultural institutions play in embedding these images within certain narratives. The room’s mezzanine space features smaller but no less poignant works. The breaths inside my mind (2016–ongoing) by the Greek artist Vangelis Gokas (b.1969) comprises portraits of poets, writers and painters rendered on five-by-four-centimetre blocks of wood: the artist’s personal pantheon reconstructed as miniature talismans. Elif Kamisli’s notebooks (2017–21) features a tarot deck and papers inside a glass display case, including handwritten notebooks and novel manuscripts. The work reimagines Kamisli’s identity as a woman writer in politically turbulent modern Turkey through a blend of fact and fiction.

Perhaps one of the more uncanny sensations of the pandemic is how domestic life has become both strange and heightened in its repetitive mundanity. In room two sculptural works by Daphne Wright (b.1963) transform everyday objects into frozen, oddly fragile replicas of themselves: a row of towering dark sunflowers, bent and sad FIG.4; a grey cactus beneath a desk lamp. The wall-mounted work TIGHTROPE: ECHO!? by Elias Sime (b.1968) FIG.5 conjures a swirling tapestry of muted pinks and mints, with a centre of bright emerald green. On closer inspection this central component crystallises into recycled electrical wires and parts, suggesting the missed connections and disrupted flow of locked-down life. Upstairs, on the mezzanine level, Cornelia Parker (b.1956) asks what tensions can be sustained under the putative banner of ‘freedom’. Her Magna Carta (An Embroidery) from 2015 is a thirteen-metre facsimile of the Wikipedia entry for the royal charter of rights. Hand-woven by approximately two hundred people – from prison inmates to judges – it is a boldly democratic creative act that invokes liberty as many-voiced and precarious, not least in the face of technological change.

In another room, the exhibition explores how ideas of home have changed while living in isolation. The installation 348 West 22nd St., Apt. A & Corridor, New York, NY 10011 by Do Ho Suh (b.1962) FIG.6 is a beguiling recreation of the artist’s apartment, with tent-like rooms made of translucent cotton-candy-pink and pale blue nylon. Every feature, down to the thermostat, is transformed into its flimsy, sensual double. Robert Gober’s Pitched Crib (1987) is a disquieting piece of trompe l’œil: a baby’s cot that, from every angle, looks close to collapse. Photographs by Paul Mpagi Sepuya (b.1982) play on the voyeuristic and unsettled eroticism aroused by quarantined life; showing faces and body parts truncated or obscured, they evoke the sense of looking and being looked at through camera lenses and windows.

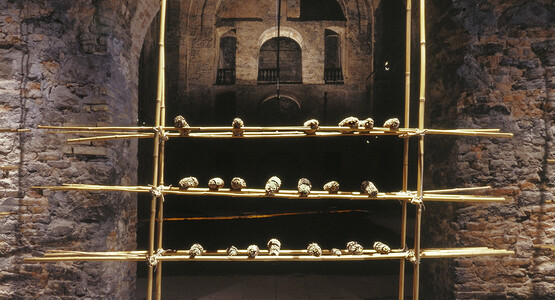

Designed to mimic a loft, the room’s mezzanine features several sculptural works. Fear by Nikos Alexiou (b.1960) FIG.7 is a teetering assemblage of miniature paper boxes. Painted in watercolour washes of pink and yellow, it manifests as an attempt to order our own lingering anxieties about societal and political precarity. Crawling along the gallery walls, nested in the cornices like alien forms, Interference, Noise and Message (The Parasite Series) (2020–21) by Alexandros Tzannis (b.1979) strikes an even more ominous note. Constructed from jagged pieces of metal and resin, pulsing with siren-blue neon light, they suggest an interior colonised by parasites: dark mirrors for our own bubbling psychoses. The End of Imagination (2021) by Adrián Villar Rojas (b.1980) is a document of the loneliness felt in the wake of disaster. Two banks of LCD television screens broadcast public webcam footage from various internet sources from March 2020. The top row appears to show a chain-link fence in the dark; underneath we see orangutans idling in a zoo, rolling in the dirt or mauling one another’s fur. Here is all the ecstatic boredom of the early days of the pandemic: an eerie window onto its atomisation and aimless drift.

A Monumental Lightness by Maria Loizidou (b.1958) FIG.8 – an ethereal fringe of silk threads hanging over the entrance to the Tobacco Factory’s central agora – suggests a membrane between one world and another. The light installation Waiting for the Barbarians by Glenn Ligon (b.1960) FIG.9 dominates the main exterior wall: an attempt, stuttering and partial, at casting the shared net of language across the gulf between meaning and interpretation. The work comprises fragments of text, taken from a 1904 poem by Constantine P. Cavafy, in multiple English translations, each echo amplifying the original.

Taken in its exhaustive – and often exhausting – entirety, Portals captures the pandemic as both agent of devastation and spur for potential change. At times, its scale also mimics too well the sensation of helplessness in the face of sensory overload. However, for all its vastness and scope, the show successfully catalogues an artistic response to the crisis in a multiplicity of voices and nationalities. Works are grouped by interlinking themes and concerns, creating connections across the distorted sense of time and space imposed by COVID-19. As the sum of its parts, it boldly emphasises Roy’s clarion call: after the great rupture, what next?