We, a part of them: Laura Anderson Barbata and the disassembly of border regimes

by Madeline Murphy Turner • June 2021

The concept of borders has been heightened amid the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as the New York Times Editorial Board wrote in March 2020, the virus itself refuses to obey national or socio-economic boundaries: ‘the coronavirus does not care which passport its human hosts may carry or tongue they speak’, arguing that social distancing and hand washing are ‘best practices that should transcend borders and walls and help us acknowledge our common plight, and humanity’.1 Although the virus has exposed the irrelevance of borders to the most minute organisms of the world, it has nonetheless afforded far-right anti-immigration politicians the opportunity to enact the policies they have long advocated for, and has given racist ideologies the chance to violently expose themselves.

In a time when even the rhetoric of ‘native’ and ‘foreigner’ has been applied to non-human pathogens, it is critical to closely examine borders in all their forms. A recent issue of emisférica, edited by Macarena Gómez Barris and Marcial Godoy-Anativia and dedicated to the theme of expulsion, demonstrates the urgency of interrogating how state regimes extract power through designations of citizenship in the Americas.2 Most importantly for the present article, Nicholas De Genova proposes that borders are ‘better seen as sociopolitical relations’.3 He cautions against the depiction of territorial boundaries as fixed realities, reminding us that ‘the movement of people around the world, and hence across these border zones, came first. The multifarious attempts to manage or control this autonomous mobility have always come as a response’.4 As a conjunction of sociopolitical relations, the border is intimately tied to the bodies that move across and between it.

This article analyses the work of Mexican-born artist Laura Anderson Barbata, elucidating the ways in which her projects – which disclose how memory, history and knowledge are inextricable from the body – unmask borders as oppressive colonial constructs. Building on a limited corpus of writing that locates her practice within contexts of border-crossing, it argues that beyond contending with the border as a facet of the state, her practice confronts the colonial mechanisms that partition human bodies and identities.5 This approach looks towards scholarship that recognises the power strategies at play in border-making processes. Following Gabriel Popescu, it is possible to see how the ‘territorialization of difference’ is an exclusionary manoeuvre of power. Popescu elaborates that this form of societal structuring ‘determines membership in society: who belongs where, who is an insider and who is an outsider, who is part of us and who is part of them’.6 Through her artistic practice, Anderson Barbata works with communities to disassemble these power structures by focusing on the territorial and neocolonialist borders that are inscribed between humans.

To oppose this ‘territorialization of difference’, the artist dedicates herself to projects that centralise embodied experience. Arguing that our entire perception and experience of the world is embodied, Maurice Merleau-Ponty explained the lived body as a social agent and rejected the mind–body dualism that has long dominated Western thought.7 From a feminist perspective, a number of scholars – most notably Simone de Beauvoir and Luce Irigaray – have argued for the valuation of lived experiences and embodied practices to obtain and organise knowledge. For de Beauvoir, understanding embodiment is key to analysing how unique experiences of the body determine cultural assumptions of inequality.8 She examines the lived realities of women in order to argue that with the dominance of masculine ideology, sexual difference is exploited to produce systems in which the male subject is always assumed to be the absolute human type. While taking a divergent approach, Irigaray also develops a theory of the body and subjectivity, asserting that splitting the mind and body perpetuates the cultural division between man (mind) and woman (body). For Irigaray, to overcome dominant power structures that articulate truths from the male perspective, both men and women must understand themselves as embodied subjects.9 These perspectives recognise that embodiment can dismantle the boundaries that allow logics of domination to persist.

In order to contend with the links between embodiment and borders, this article turns to the decolonial theorist Walter Mignolo and the performance studies scholar Diana Taylor. Theorising the concept of border thinking – that is, to decolonise knowledge – Mignolo explains how the ‘subalternization of knowledge’ minimises those forms of human understanding that are expressed outside the Western colonial system of alphabetic writing, such as embodied knowledge.10 In line with this thinking, Taylor details how pre-Conquest, indigenous cultures of the Americas prioritised embodied knowledge over writing.11 In conjunction with the archive, which stores history through mapping, texts, letters and other ‘official’ documents, Taylor proposes the concept of the repertoire to elaborate how embodied practice facilitates vital acts of transfer – meaning the transfer of memories, traditions and claims to history. The repertoire, Taylor writes, ‘allows for an alternative perspective on historical processes of transnational contact and invites a remapping of the Americas [. . .] by following the traditions of embodied practice’.12 While a number of artists working across the Americas address questions of borders and the body, Anderson Barbata’s artistic approach articulates the interrelated border-making practices that divide territories and bodies, and demonstrates that embodied practices can pose a challenge to oppressive power structures.

Origins

Since the early 1990s Anderson Barbata has worked in the social realm with a multidisciplinary practice that centres on the circulation and exchange of knowledge and language. She began her artistic explorations in the mid-1970s while studying philosophy and architecture in her native Mexico City. Later she went on to study sociology and anthropology at the University of California, San Diego and, in the early 1980s, sculpture and printmaking at the Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In 1986 she began a series of works on paper titled The Sacred and the Profane FIG. 1, which highlighted links between the self and nature through the use of images of seeds and germination. Exhibited at the Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro in 1992 as part of the show Eco Art 92, one of the works from this series, titled Los frutos pasarán la promesa de las flores (The Fruits Will Pass the Promise of Flowers), was awarded a prize that provided Anderson Barbata with a fully funded residency in Caracas, Venezuela.13

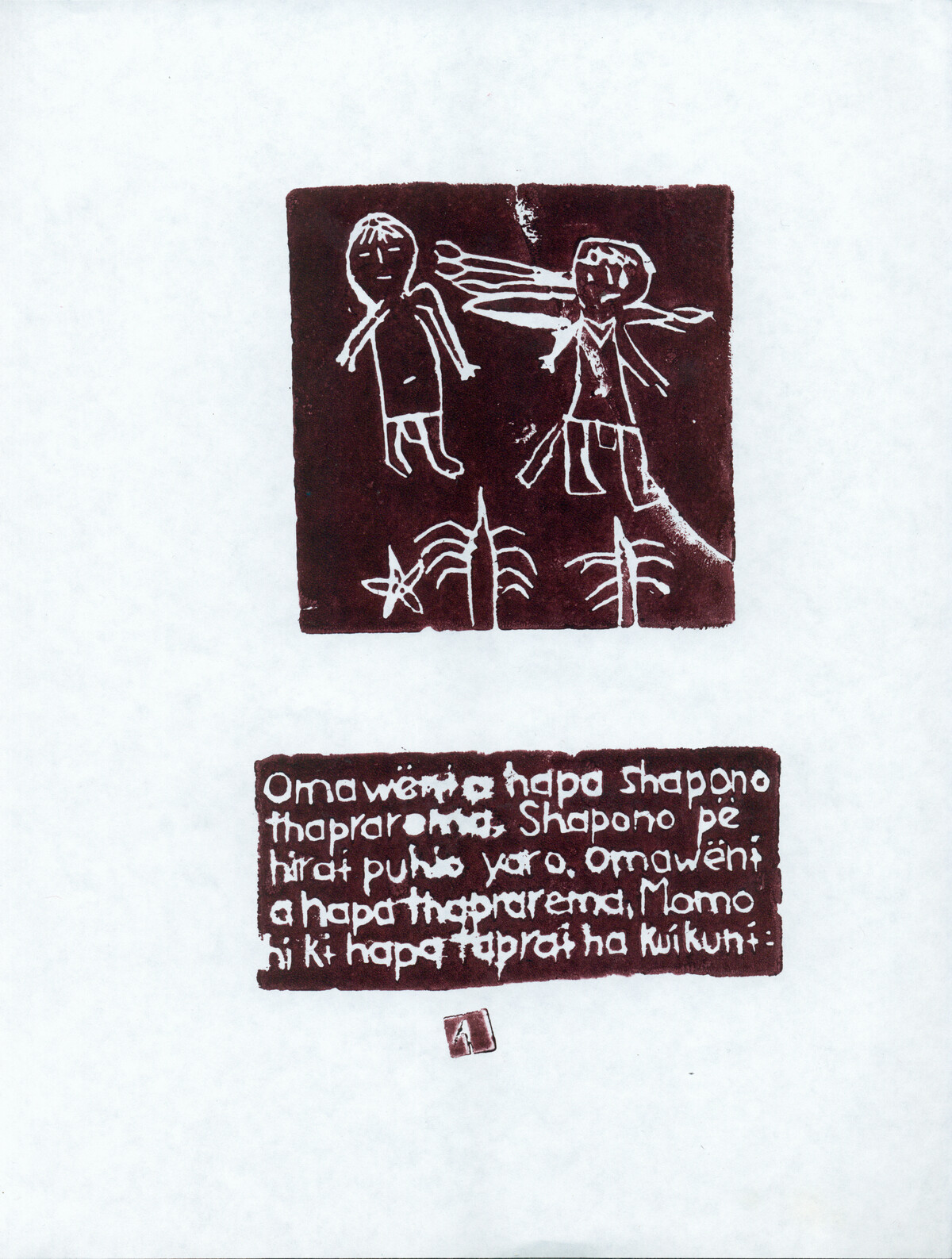

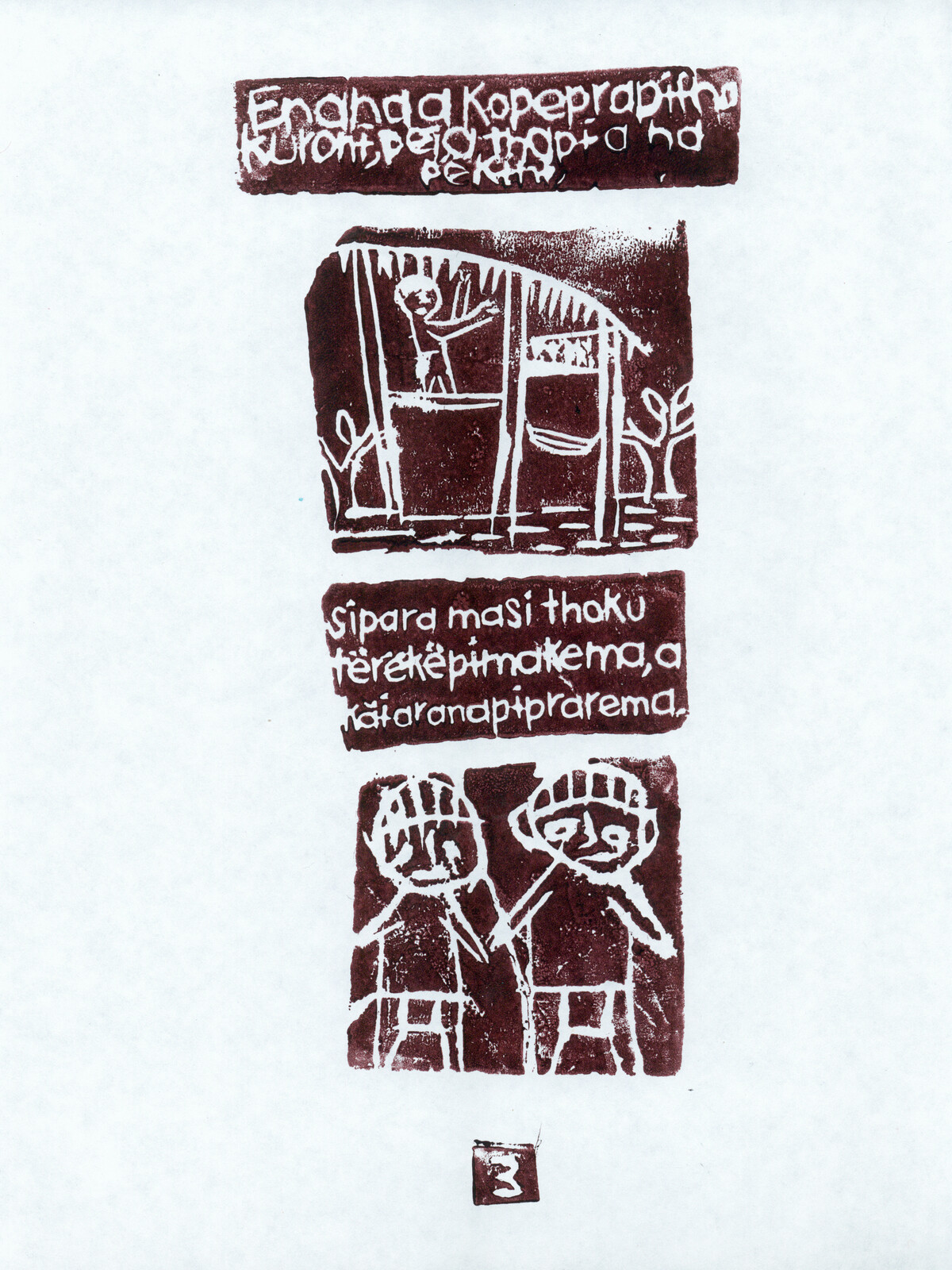

On the recommendation of the Venezuelan performance artist Carlos Zerpa and the critic Axel Stein, Anderson Barbata took the opportunity to travel to the country’s Amazon region.14 This trip proved to be transformative for the artist. After seeing members of the Ye’kuana making traditional dugout canoes – a highly collaborative process – Anderson Barbata asked if they would accept her as an apprentice. They responded with a question that has marked her life and career: ‘What can you teach us in return?’15 She proposed to implement a papermaking project with the local Yanomami, Ye’kuana, and Piaroa communities. The Yanomami used this new practice to inscribe and circulate their own histories, therefore taking control of the ways in which their narrative has been constructed. In 1996, Shapono, the first book that the artist realised with the Yanomami Owë Mamotima Project in Platanal, was completed FIG. 2 FIG. 3.16 Written in the Yanomami language and illustrated by children from the community, it features a story that is traditionally passed down orally and had previously been transcribed only by visiting anthropologists.17 Although the outcome of such a book points to a continued centrality of the archive, the exchange of knowledge systems between Anderson Barbata and the Yanomami, Ye’kuana, and Piaroa communities speaks to the coexistence of the repertoire of actions alongside the archive

The colonial matrix of power

In 1998, five years after establishing a studio in New York City, Anderson Barbata held an exhibition titled In the Order of Chaos at the Dieu Donné Papermill Gallery, Brooklyn. The body of work on display continued the artist’s engagement with themes of language, and explored the detrimental effects of colonialism in the Americas through sculptural installations that primarily utilised natural materials, such as pearls, seeds, wood, paper, leaves and human teeth.

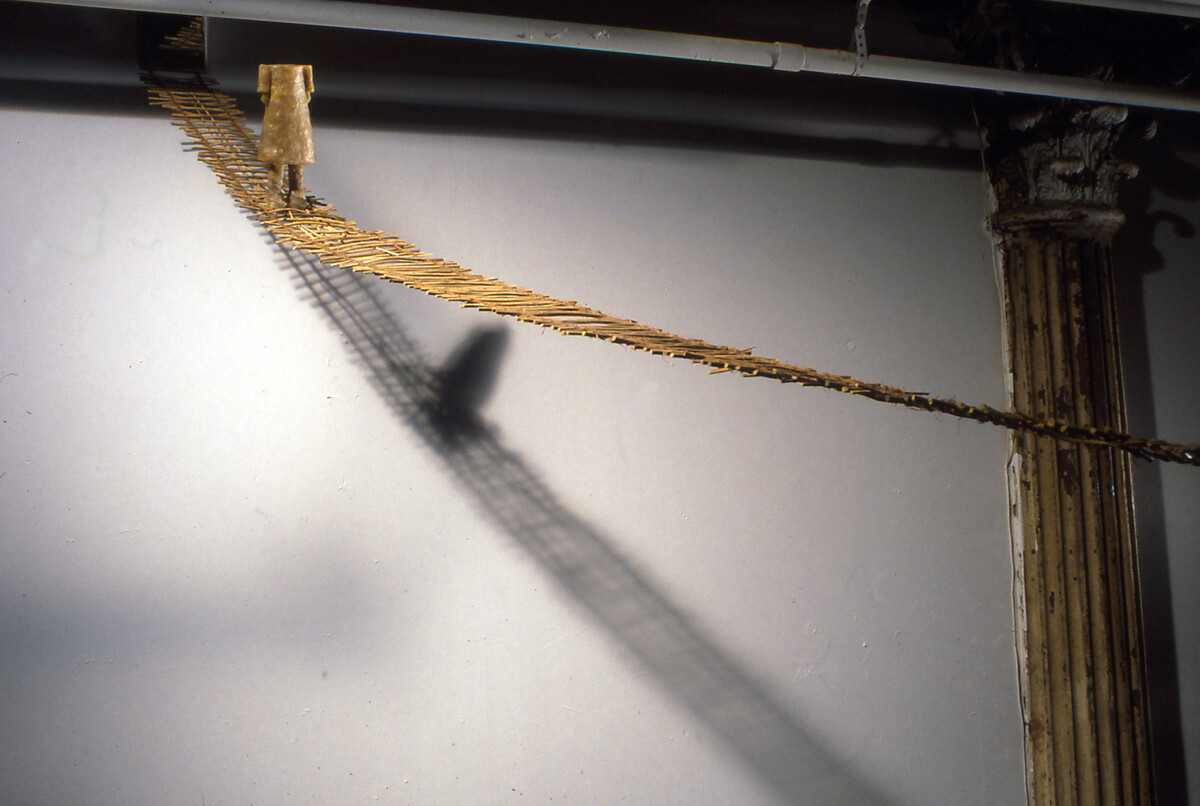

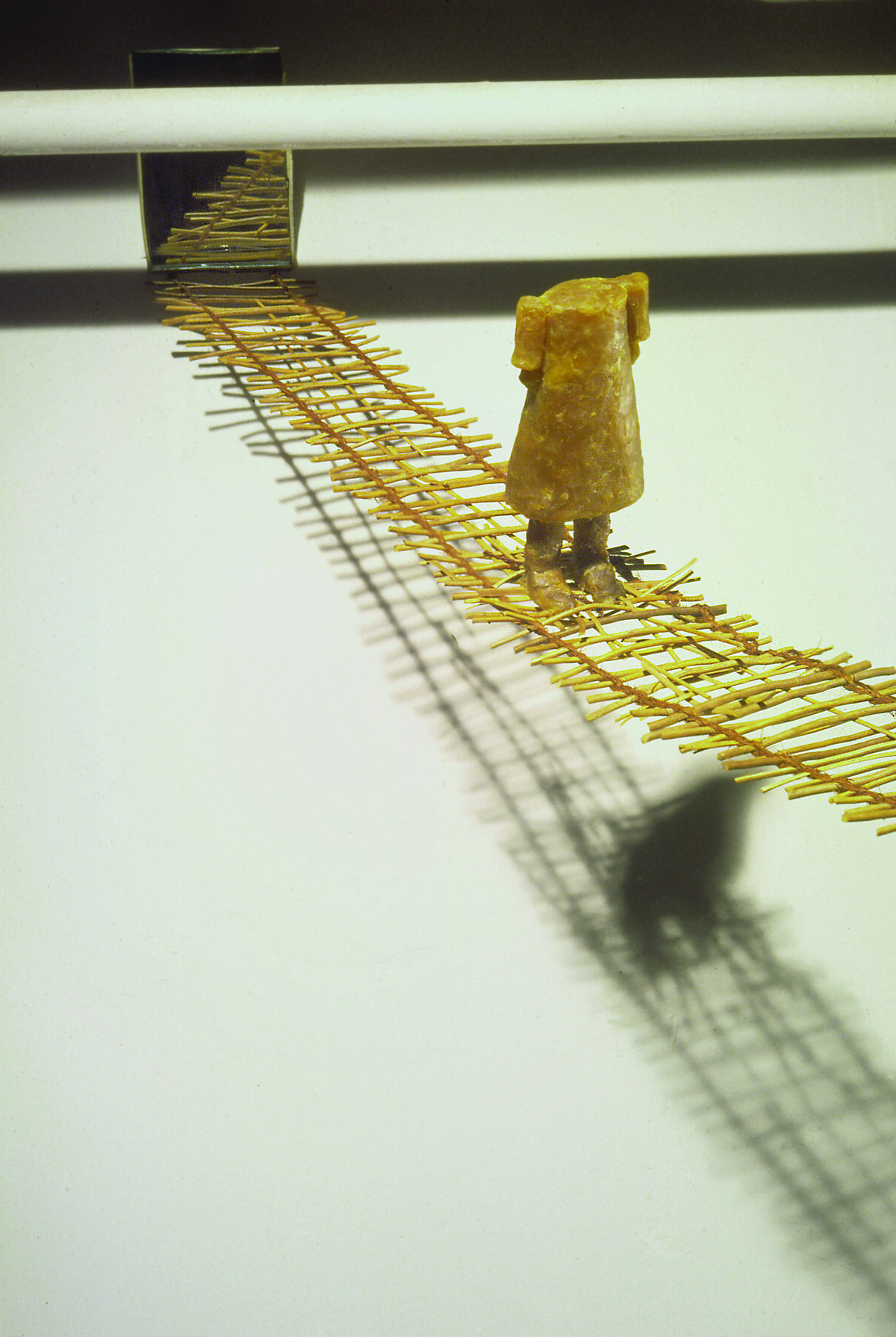

The exhibition included Epitome or easy method of learning the Nahuatl Language (1996), a large installation that features sixty-two sculptures of corn made from teeth and hair displayed on a bamboo structure FIG. 4 FIG. 5.18 Alluding to the native Mexican crop, the ‘corn’ references a cultural symbol and dietary staple, while the teeth, in their extricated state, represent the loss of indigenous language through processes of colonial extraction of resources, labour and life. This work, along with others in the exhibition – such as Anderson Barbata’s 1996 self-portrait FIG. 6 FIG. 7 composed of a small wax headless figure crossing a bridge made of rattan, rope and mirrors – are emblematic of the artist’s intensive manual skill, but also her interest in the intricate ties between the natural world and the body, and how humans receive, store and share knowledge.

The headless figure is a recurring motif throughout Anderson Barbata’s practice and expresses the necessity to see the world from various perspectives. Works such as the headless wax self-portrait and a series of headless Virgins from the early 2000s, including Consuelo FIG. 8, interrogate a reliance on the eyes and mind to engage with the world, and instead shift perception to the body. In an interview about the 1996 self-portrait, the artist states:

I understood who I was and what was happening: that I walk over the bridge without a head because what guides me is not my head nor my eyes, but the interior, which has its own way of seeing and its own way of thinking, and that way of seeing and thinking is going to ensure that I do not fall from the bridge, that I arrive to the other side without falling. I understood that, to be able to see the world, I had to remove my head.19

In reorientating a perception of the world toward the body, Anderson Barbata not only rejects vision and the mind as primary forms of obtaining knowledge, but also engages with a history of feminist thinking, proposed by such scholars as de Beauvoir, Irigaray, Susan Hekman and Val Plumwood, that problematises mind–body dualism on the grounds that it has justified domination and subordination. In this oppressive conceptual framework, as the ecofeminist scholar Karen J. Warren calls it, the mind represents rationality, impartiality and independence, while the body represents the emotional, irrational and passive. It is a dualism that has been mapped onto the social attributes of masculinity and femininity, which deem the former to be the rational and active mind while the latter is the irrational and passive body. Furthermore, this dualism is reproduced in the nature–culture divide, which ties culture to the mental realm (male) and nature to physical existence (female). This epistemological binary promotes what Warren calls ‘Up-Down’ thinking, which legitimates inequality by attributing greater value to certain genders (male) and races (white), and prioritises culture over nature. It is a logic that turns difference into domination and rationalises that domination to promote racism, sexism and naturism.20 With her headless figures, Anderson Barbata frees the human of the mind, emphasising the power of the body and emotion. In this sense, ‘woman’ is liberated from the patriarchal dualism of mind–body that has oppressed her.

The headless Virgins, furthermore, confront dominant conceptual frameworks through decolonial processes. By beheading the Virgin Mary – a Christian symbol employed during the Conquest of the Americas – Anderson Barbata releases the Virgin from the weight of her historical role as the feminine ideal: an instrument of manipulation, cruelty and violence in its facilitation of a binary opposition between the pure woman and the devious non-woman. As Mignolo explains, this opposition was part of the colonial matrix of power in its demarcation of European women from African and indigenous women in the Americas, who were not considered ‘proper’ by Christian men.21 Consequently, removing her head and subverting her pristine image releases the Virgin from the matrix of power that has been wielded over not just women, but those who exist outside the boundaries of the male, white, Christian, heterosexual and non-disabled.

Transcommunality

In 2001 Anderson Barbata was invited by Contemporary Caribbean Arts (CCA7) to Grande Riviere in Trinidad to initiate GRAS, an ongoing papermaking project that creates the possibility for local children to make art using recycled materials.22 While in the Trinidadian capital Port of Spain, she began to work with the Dragon Keylemanjahro School of Arts and Culture, which teaches the Afro-Caribbean traditional practice of stilt dancing. Anderson Barbata made wearable sculptures out of recycled materials for the Moko Jumbies, as the local performers call themselves. This collaboration led to one of her most recognised projects, Transcommunality. Two of the wearable sculptures that Anderson Barbata made in Trinidad, including The Cheeseball Queen, were exhibited in the 2014 travelling exhibition Caribbean Crossroads of the World, a show that articulated the Caribbean as a region shaped by migration and diversity FIG. 9.

An ongoing, collaborative endeavour, Transcommunality is exemplary, in both name and execution, of Anderson Barbata’s transnational work. Following its conception in Trinidad, the project has since developed to feature such stilt dancing troupes as the Brooklyn Jumbies, based in Brooklyn, New York, and the Zancudos de Zaachila from Oaxaca, Mexico. Anderson Barbata invites these groups and others to perform together in many environments, such as Oaxaca in 2012 FIG. 10 or Monterrey, Mexico in 2014 FIG. 11. For the former, Anderson Barbata asked traditional artisans from the southwestern Mexican state to participate by contributing their specific talents, which included intricately made wax flowers and painted animal sculptures called alebrijes that were affixed to the stilts. To accompany these elements, Anderson Barbata created wearable works of art, composed of materials ranging from Oaxacan textiles to the fibres found in the Venezuelan Amazon that the artist used to make paper with the Yanomami.

An embodied practice, contemporary stilt dancing unearths violent colonial histories of human circulation as well as the extent to which borders have been imagined, constructed and deconstructed over time. Evidence suggests that the Moko Jumbie stilt dancing tradition came to the Caribbean through the slave trade from West Africa, specifically from the upper Guinea Coast to north-western Cote d’Ivoire, as well as south-eastern Nigeria.23 However, current iterations in the Caribbean likely unite hybrid influences from regions not only in West Africa, but also in Europe and the Americas.24 The name Moko Jumbie comes from the homonymous effigy or god that towers over the community, protecting them by scaring away evil spirits; their appearance was thought of as a good omen.25 The Oaxacan stilt dancing tradition, on the other hand, can be traced to the Maya in pre-Conquest times. In the 1566 Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán, the Spanish Franciscan priest Friar Diego de Landa recounts the Maya performing stilt dancing. Detailing the series of sacrifices that the civilisation made to not be plagued by evil in the new year, de Landa writes that they ‘were having dances on tall stilts, with offerings of heads of turkeys, bread and drinks made of maiz’.26 Further reference to the practice of stilt walking can be found in the Maya’s own narratives, particularly the Popol Vuh, which describes the Hero Twins walking on stilts while dressed as in the Maya underworld Xibalba.

The shared themes at the base of these cultural practices – faith, celebration and protection – exemplify the constructed nature of national boundaries and expose the intertwined relationship between people who are now divided by territorial labels such as Mexican, American, Trinidadian or Ivorian, without attempting to dissolve differences. The interaction between the Brooklyn Jumbies and the Zancudos de Zaachila can be elaborated through Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei Shih’s concept of minor transnationalism, which the scholars posit as a methodology to think transversally between regions in order to create relational dialogues among distinct minority groups. They argue that minor transnationalism counters vertical structures of power that, through universalism and globalisation, require assimilation and erase cultural particularities, explaining, ‘More often than not, minority subjects identify themselves in opposition to a dominant discourse rather than vis-à-vis each other and other minority groups. We study the center and the margin but rarely examine the relationships among different margins’.27 Minor transnationalism responds to French deconstructive procedures, specifically those of Jacques Derrida, which frequently maintain focus on the colonising, European centre, even while critiquing it, thus containing marginality while trying to undo the binary of the centre–periphery. According to Lionnet and Shih:

What is lacking in the binary model of above-and-below, the utopic and the dystopic, and the global and the local is an awareness and recognition of the creative interventions that networks of minoritized cultures produce within and across national boundaries. All too often the emphasis on the major-resistant mode of cultural practices denies the complex and multiple forms of cultural expressions of minorities and diasporic peoples and hides their micropractices of transnationality in their multiple, paradoxical, or even irreverent relations with the economic transnationalism of contemporary empires.28

In this sense, minor transnationalism endorses a perspective that thinks across the borders of those regions that have been minoritised through processes of colonisation without maintaining the coloniser in the position of the dominant discourse. It also facilitates a deeper understanding of Anderson Barbata’s transnational and transdisciplinary practice, which prioritises traditions and seeks to build bridges between cultures that have historically been oppressed by European and North American power structures. Following the art historian Kaira M. Cabañas, the present author suggests that Anderson Barbata’s artistic practice resists the global contemporary framework in which ‘“other” art histories are put to work as “global art” in exhibitions that display confidence in the ability of similar forms to be read as a global art history’.29 Cabañas calls this phenomenon ‘the monolingualism of the global’, in which distinct artistic practices lose their history and cultural specificity, becoming engulfed in ‘a formal and timeless art history passing itself off as contemporary and global’.30 Assimilation at its most powerful, the global contemporary, as Cabañas evinces, disavows discontinuity and difference.

While Anderson Barbata’s work has resisted the global contemporary framework, it has also been left out of many surveys of contemporary Mexican art. Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, a series of exhibitions and scholarly publications have attempted to piece together a narrative of the nebulous contemporary art scene in Mexico. These include MoMA PS1’s exhibition Mexico City: An Exhibition about the Exchange Rates of Bodies and Values (2002); Ruben Gallo’s book New Tendencies in Mexican Art: the 1990s (2004); Eco: arte contemporáneo mexicano (2005) at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid; Olivier Debroise and Cuauhtémoc Medina’s book The Age of Discrepancies: Art and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1968–1997 (2007); and, most recently, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth’s exhibition México Inside Out: Themes in Art Since 1990 (2014). Although Anderson Barbata was exhibiting her work actively in Mexico during the 1990s and early 2000s – in notable venues such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, Museo Universitario El Chopo and Ex Teresa Arte Actual – she was not included in the previously listed surveys.31 In their efforts to create a cohesive idea of Mexican contemporary art, these exhibitions and publications continuously featured Eduardo Abaroa, Francis Alÿs, Minerva Cuevas, Teresa Margolles, Daniela Rossell, Melanie Smith and Gabriel Orozco – artists who were framed as confronting the political and social issues of Mexico. Although some of these artists make work that deals with the US–Mexico border, many of the previously listed surveys, particularly those at MoMA PS1 and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, emphasised the centrality of Mexico as a subject itself in defining Mexican art. One of the few large-scale thematic group exhibitions in which Anderson Barbata was included is the aforementioned Caribbean Crossroads of the World, which took as its central premise interdisciplinary, border-crossing forms of exchange throughout the titular region. As an artist whose perspective is intimately tied to exposing the sociopolitical nature of borders in collaboration with communities outside the delimitations of her native country, Anderson Barbata’s work cannot fit neatly into classifications grounded in contemporary national tendencies.

This reflection on the exhibition history of Anderson Barbata’s work extends to the central role of practices that are often referred to as craft in the context of a Western and globalised discourse. When considering either the textiles produced by Anderson Barbata or the alebrijes and wax flowers created by her collaborators, it is pertinent to ask whether such a component has deterred curators from including her work in thematic contemporary art exhibitions. The art historian and curator Roger Nelson has recently argued for renewed attention to objects and practices that the global art world frequently identifies as ‘handicraft’, in order to situate definitions of the modern and contemporary outside of the Western criteria they are frequently relegated to.32 Furthermore, Julia Bryan-Wilson has explored the role of textiles in South America and how they can ‘figure contemporaneity’, revealing the arbitrary nature of categorising practices of craft based solely on their functional qualities or their creator.33 While it is important to examine the contexts in which craft has been either embraced or ignored by the Western and global contemporary, following Bryan-Wilson, the present author is uninterested in the high–low dualism that often dominates the discourse of craft. In contrast to figures such as the Guatemalan artist Sandra Monterroso or the Brazilian artist Sonia Gomes, Anderson Barbata refrains from aligning her work with the status of craft and its relegation to the margins. Instead, her work, as previously articulated, is engaged with how these expert practices of embodied labour facilitate the exchange of knowledge between humans of varying cultures.

Amid the small and large-scale collaborations for projects such as Transcommunality, Anderson Barbata is, according to the art historian Edward J. Sullivan ‘the entrepreneur, catalyst, artistic enabler, and integral participant of all these efforts’.34 She is a producer of exchange, facilitating linguistic, corporeal and symbolic dialogues between individuals from diverse cultures. With this role in mind, it is crucial to acknowledge the privilege that Anderson Barbata carries from her position as an artist with access to international travel. Working among BIPOC communities for extended periods of time, she leverages her platform to centralise the practices and perspectives of her collaborators. In Transcommunality, this is exemplified by the fact that she herself never walks on stilts, but instead remains below to coordinate the multiple moving parts of a performance, acting as a facilitator for the final execution. Anderson Barbata’s resistance to the ‘monolingualism of the global’ is further demonstrated in an interview about Transcommunality’s recent iteration, Intervention: Indigo. The artist states:

My collaborators are the owners and custodians of their traditions and practices. I invite them to participate in the way that they feel is most appropriate. At the beginning, the process of a project involves multiple meetings, conversations, encounters, exchanges of ideas and objectives, we explore the theme, discuss the intention of the project, but ultimately in every participant there is a great freedom to present their own tradition in the way they feel is theirs.35

Intervention: Indigo arose from the urgent need to disrupt public space in order to reclaim it from systemic forms of oppression and surveillance enacted by the police in Bushwick – the Brooklyn neighbourhood where the artist lives and works. Moving through the streets and stopping in front of the neighbourhood’s police precinct, the Brooklyn Jumbies, led by principals Ali Sylvester and Najja Codrington, wore indigo-dyed works of art created by Anderson Barbata. Indigo is an ancient natural dye that is employed in rituals of protection, power and spirituality.36 Today it is worn by police forces around the world and, most visibly since the spring of 2020, by the officers throughout the United States who have openly violated the lives of Black and brown citizens. In this sense, the symbolic meaning of the colour alters across the bodies who wear it.

A project that is built on the continuous exchange of embodied knowledge, Transcommunality treats the border as an unstable sociopolitical construction. Following Taylor’s theory of the repertoire, the project highlights the body’s ability to enact memory through movement, dance, gesture and performance, demonstrating that, indeed, traditions of embodied practice pose an opportunity to remap the Americas.37 It is, however, also worth emphasising that, in line with Joseph Roach’s concept of surrogation, the performance of memory is a process of invention that is always implemented in the presence of others and by ‘staging contrasts with other races, cultures, and ethnicities’.38 Memories, Roach writes, can ‘torture themselves into forgetting by disguising their collaborative interdependence across imaginary borders of race, nation, and origin’.39 In other words, throughout the circum-Atlantic world, societies, in their self-perception, often define themselves in opposition to others: to what they believe they are not. The concept of minor transnationalism provides another way of analysing how the formations that Roach proposes can take place transversally between minor cultures that do not inhabit the realm of the dominant discourse. Rather than a delimitation of sovereign power, the border is exposed, in De Genova’s words, as ‘flexible and mobile formations of power in which there are a multiplicity of activities and actors engaged in struggle’.40

The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana

In recent years, Anderson Barbata has advanced her focus on borders that divide certain humans from others through power dynamics of domination. In her ongoing project The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana (2004–present), the artist continues to excavate the mechanisms of colonialism that implement national boundaries. Here she focuses on their place in a history that demonstrates how those matrixes of power led to divisive categorisations of human and ‘other’. Julia Pastrana (1834–60) was an indigenous Mexican woman born in the state of Sinaloa.41 She was a mezzo-soprano opera singer and accomplished dancer who was known internationally as the ‘Marvelous Hybrid’, or ‘Bear Woman’.42 Born with hypertrichosis terminalis, a condition that causes excessive bodily and facial hair growth, Pastrana was ‘exhibited’ in the United States and Europe, both in life and death. In her analysis of the advertisements for Pastrana’s exposition, the disability studies theorist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson writes, ‘Julia Pastrana’s body radically violated expectations of how human beings should appear [. . .] [her body] generated multiple, sensational narratives of hybridity, wonder, exoticism, and delightful deviance’.43 Treated as a commodity, Pastrana’s actions were closely monitored by her unscrupulous North American husband and manager, Theodore Lent, who controlled the profits of her performances. In 1860 Pastrana died giving birth to a baby with the same genetic condition, who also died shortly after. Lent sold their bodies to the Anatomical Institute at Moscow University where they were embalmed. Soon after, he repurchased their preserved corpses and continued to show them internationally in exhibition halls, museums and travelling circuses.44 They circulated for over a century, until their bodies ended up at the basement storage of the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Oslo in the late 1970s.

Anderson Barbata learned about Julia Pastrana in 2003 and subsequently initiated a process to have her body repatriated to Mexico. In 2013, 153 years after her death, Pastrana was given a traditional Catholic mass and ceremony in her birthplace. An effort to restore the rights that had been denied to the titular figure, The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana takes many forms: social intervention, animation, photography, performance and opera. Highlighting the dignity that Pastrana had been deprived of, Anderson Barbata stated, ‘It was my belief that if I could shift the understanding of Pastrana as part of a large institution to Julia as an individual, it would promote compassion and empathy as well as a change in conduct toward her’.45 While this project involves the subject of national borders in terms of Pastrana’s circulation and, later, in Anderson Barbata’s negotiations between the Norwegian and Mexican governments, the question of the constructed social borders that attempt to divide certain humans from others is fundamental to The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana.

The treatment of Pastrana in life and death is part of a long history of colonialism, which largely empowered white, Christian, non-disabled men by classifying all others as ‘lesser’ forms of human, if human at all. It is, unfortunately, a common history, one of the most well-known examples being Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman born in the late eighteenth century, who was ‘examined and prodded for [her body’s] racial and sexual alterity’, as the anti-colonial studies scholar Katherine McKittrick explains.46 She had a condition called steatopygia, which causes excessive tissue to develop around the legs and buttocks. Like Pastrana, Baartman was put on display for spectators and scientists throughout Europe and, following her death in 1815, her brain, skeleton and sexual organs continued to be exhibited. Her remains were finally repatriated to South Africa in 2002, 187 years after her death.

Working within an ecofeminist framework, Warren elaborates a series of oppressive conceptual systems, one of which she argues encourages ‘oppositional value dualisms’ in which disjuncts are perceived to be exclusive and oppositional rather than inclusive and complementary. Examples include value dualisms that give higher status to that which has historically been identified as ‘male’, ‘white’, ‘rational’, or pronounced to be part of ‘culture’, than to that which has been defined as ‘female’, ‘black’, ‘emotional’, or part of ‘nature’.47 Furthermore, addressing the colonial roots of human categorisation, Mignolo speaks to how systems of binary opposition emerged with the formation of modernity via the logic of coloniality. He writes, ‘This Man/Human who created and managed the [Colonial Matrix of Power], posited himself as master of the universe and succeeded in setting himself apart from other men/humans (racism), from women/humans (sexism), from nature (humanism), from non-Europe (Eurocentrism) and from ‘past’ and ‘traditional’ civilisations (modernity)’.48 Through the various projects associated with The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana, Anderson Barbata attempts to call attention to this violent system of binary opposition, which itself relies on the sociopolitical idea of borders. These are borders that do not demarcate territory, but rather attempt to divide ‘human’ from ‘other’.

Anderson Barbata’s 2013 photographic work Julia y Laura FIG. 12 reflects the artist’s concern with questions of division and dehumanisation. The piece is composed of two digital prints: on the left is a reproduction of a retouched daguerreotype portrait of Pastrana from the late 1850s, and on the right is a contemporary photograph of Anderson Barbata. Facing each other in similar dress and posture, the two women are framed as equals despite the temporal span of more than a century. They have each given something to the other by entering into a reciprocal exchange characteristic of Barbata’s practice. At the same time, the embodied dialogue between the two women highlights the system of oppression that denied Pastrana – and many other women and people of colour – the dignity she deserved. The image calls to mind the different experiences of each subject: one, an indigenous woman with disabilities who was forcibly circulated internationally as a commodity; the other, a Mexican woman of European and indigenous origins whose access to transnational travel permits her to carry out her elected work.

In being referenced as ‘hybrid’ or ‘semi-human’, Pastrana’s body was entangled in the violent categorisation implemented by logics of domination and matrixes of power. Nineteenth-century newspaper articles and advertisements never fail to highlight the titillating disjuncture between her physical appearance and her cultural refinement: she spoke multiple languages, could cook, clean and sew, she was good natured and had a ‘dulcet voice that enchants the ladies’.49 From today’s perspective, examining the dialogue that attempted to define her body reveals the extent to which colonialism has forcibly imposed borders to separate bodies into categories of binary opposition.

The Repatriation of Julia Pastrana can be considered within a frame of contemporary art that confronts the histories of colonialism, border regimes, and the restrictions these systems of power inflict on human bodies. From 1992 to 1994, the performance artists Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez Peña performed the role of two ‘undiscovered Amerindians’ who were exhibited in a cage that travelled for two years to a number of metropolises. The piece, The Year of the White Bear and Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit the West FIG. 13 was conceived of to coincide with the quincentennial of Columbus’s arrival to the Americas, and satirically evoked the long history of the display and circulation of caged indigenous people from the Americas, a history that includes Pastrana. Confronting contemporary migration and the ties between dehumanisation and border regimes, Regina José Galindo’s 2008 performance America’s Family Prison FIG. 14 at Artpace San Antonio placed the artist, her husband, and her infant daughter in a rented detention cell used to incarcerate families of undocumented immigrants. The family occupied the cell for thirty-six hours, during which time visitors could peer through the window to observe them and a video camera monitored their actions. Although these works take as their subject minoritised bodies that have been subjugated and separated into a category of the other, Anderson Barbata’s practice stands out for its emphasis on counteracting the effects of such dehumanising systems. Rather than re-enacting narratives of oppression, she focuses on human bodies who are directly entangled with such systems and highlights their relationships, interactions and knowledge to undermine the power of border regimes.

We, a part of them

Borders, their effects and their ties to the body are also central to the writing of the late Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa (1942–2004), particularly in her renowned book Borderlands/La Frontera (1987). The first of its kind to detail the concrete impact of the Mexico–US border on individuals and the culture that emerges from that geographical division, the book is a hybrid of poems and essays that reference the author’s experiences growing up in an ‘unnatural boundary’. Raised in the Rio Grande Valley, Anzaldúa consistently endured the consequences of the border, not only as a territorial imaginary, but also through the separation from heteronormative culture that she experienced from her position as a Chicana and a lesbian. She writes:

Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants. Los atravesados live here: the squint-eyed, the perverse, the queer, the troublesome, the mongrel, the mulato, the half-breed, the half dead; in short, those who cross over, pass over, or go through the confines of the ‘normal’.50

Anzaldúa’s discussion of divisions moves between those that are imposed to demarcate the territory between the United States and Mexico, as well as those borders that divide individuals by latinas/os or non-latinas/os, sexuality or gender. Significantly, Anzaldúa likens the border to an open wound, conflating the body and the border through the psychological and physical injuries imposed by its culture. In the narrative, as the scholar Hsinya Huang vividly maintains, the body ‘becomes the landscape on which the boundaries of the colonialists’ nation are inscribed and upheld’.51 Through the poetry and essays that compose Borderlands/La Frontera, Anzaldúa continuously returns to the concept of embodiment through the inseparability of borders from memory and violence.

Anderson Barbata has lived and worked between Mexico City and New York City for more than two decades. As such, her perspective, like that of Anzaldúa, has been shaped by unnatural boundaries. Arriving to the East Coast metropolis in the mid-1990s, the artist explains that her position as a foreigner made it ‘impossible not to have strong emotional and intellectual responses to the historically blatant systemic racism and violence toward people of color in the United States’.52 This statement brings us back to the start of this article and the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the height of the pandemic in New York City, Anderson Barbata drew from her shared knowledge of sewing and textiles to make dozens of protective face masks, which she donated to hospitals, homeless shelters and individuals in the city and beyond.53 For these masks, she used leftover material from Intervention: Indigo FIG. 15, embedding the face coverings with the protective possibilities associated with indigo dye. In their twofold capacity to provide safety, these face masks demonstrate Anderson Barbata’s continuous dedication to human bodies regardless of the sociopolitical power structures that attempt to separate them from one another. Although the coronavirus as a pathogen is immune to borders, it has become clear that the systems of power in place that divide humans from one another have put some communities at much higher risk than others. Numerous reports have highlighted that the virus has killed BIPOC New Yorkers at approximately twice the rate of white residents, detailing the discrepancy between private hospitals primarily in Manhattan and those that are publicly funded in lower-income areas of the city.54

Amid divisions that are constructed between and on human bodies, Anderson Barbata’s work realises propositions for developing new perspectives that can thwart the sociopolitical powers that impose these borders. In her practice, she does not attempt to globalise the human – that is, to excise our cultural and historical differences. Rather, she views differences as a way to start conversations about our shared experience of being human. By way of conclusion, the present author turns to the Jamaican cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter. Speaking in the year 2000 on the importance of reimagining the human, Wynter poetically argues:

You see, the problems that we confront – that of the scandalous inequalities between the rich and the poor countries, of global warming and the disastrous effects of climate change, of large-scale epidemics such as AIDS – can be solved only if we can, for the first time, experience ourselves, not only as we do now, as this or that genre of the human, but also as human. A new mode of experiencing ourselves in which every mode of being human, every form of life that has ever been ever enacted, is part of us. We, a part of them.55

Anderson Barbata’s practice contends with the colonial logics of domination that have divided humans, the result of which locates humans on binary sides of interrelated borders constructed across territory, gender, race and ability. In all of her projects, these borders are inextricable from questions of embodiment. By amplifying our understanding of how human beings relate to one another across nations, verbal language and time, the artist underscores the commonalities carried in and between us.

Acknowledgments

This essay would not have been possible without the guidance of Edward J. Sullivan at New York University and Kellie Jones at Columbia University, New York. An earlier version of this research was presented as part of the panel ‘Diasporic Women Artists in Latin America: Gender and Displacement in the Crafting of Multiple Modernities’, at SECAC in December 2020. I am grateful to the co-organisers, Georgina Gluzman and Caroline Olivia Wolf, for their generous feedback. Finally, I would like to thank Laura Anderson Barbata for her collaboration and dedication to this research