Martha Edelheit’s ‘Flesh Walls’: towards a communal, queer futurity

by Chiara Mannarino • November 2021

During the early to mid-1960s the American artist Martha Edelheit (b.1931) produced a series of large-scale figurative paintings. For many of her contemporaries, abstraction was a more accepted and widely practised mode of painting than figuration; Edelheit’s massive Flesh Walls depict large groups of men and women resting and reclining in the nude.1 Both erotically and platonically charged, these works allude to the countercultural movement of collective living at the time. This article will focus on Edelheit’s 1964 Study for Flesh Wall (Flesh Wall with Drawing Board) and its resulting Flesh Wall with Table and analyse the ways in which they embody queer interdependency in the context of the developing gay and lesbian communal movement in the 1960s.

To date, there has been little academic attention devoted to Edelheit’s œuvre. Although this article will address Flesh Walls from a queer perspective, this is not done in reference to the artist’s sexual biography. Instead, Edelheit’s study and painting will be positioned in relation to the theorist and scholar Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s definition of queerness as ‘along dimensions that can’t be subsumed under gender and sexuality at all’ – in other words, queerness as a type of fluidity, non-normativity and resistance that extends beyond sexual preference; queerness as an ‘open mesh of possibilities’.2 In applying such a reading, the present author will consider how Edelheit’s Flesh Wall with Table is therefore open to a wider range of interpretations and examine the ways in which it visually evokes a utopian living space far from reality while simultaneously revealing the impossibility of achieving it in practice.3

Edelheit’s ‘Flesh Walls’

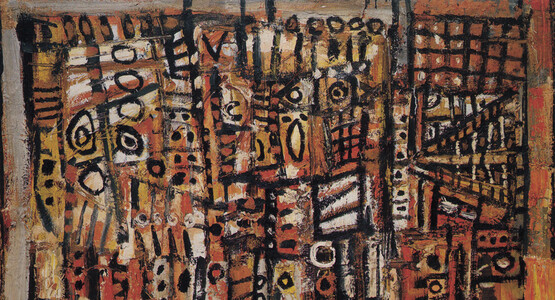

In the 1950s during an apprenticeship with Michael Loew (1907–85), an Abstract Expressionist painter from New York, Martha Edelheit was introduced to the principles of geometric abstraction.4 Loew’s purism and unwavering devotion to the tenets of formal abstract composition, however, proved to be unfulfilling for Edelheit, who eventually discovered that working with live models and painting from life was far more inspiring to her work.5 Edelheit’s first solo show was held in 1960 at the Reuben Gallery, an artist-run space on New York’s 10th Street, of which Edelheit was a member along with such artists as Rosalyn Drexler (b.1926), Allan Kaprow (1927–2006), Claes Oldenburg (b.1929) and Lucas Samaras (b.1936). Her second was staged at the Judson Gallery, New York, the following year.

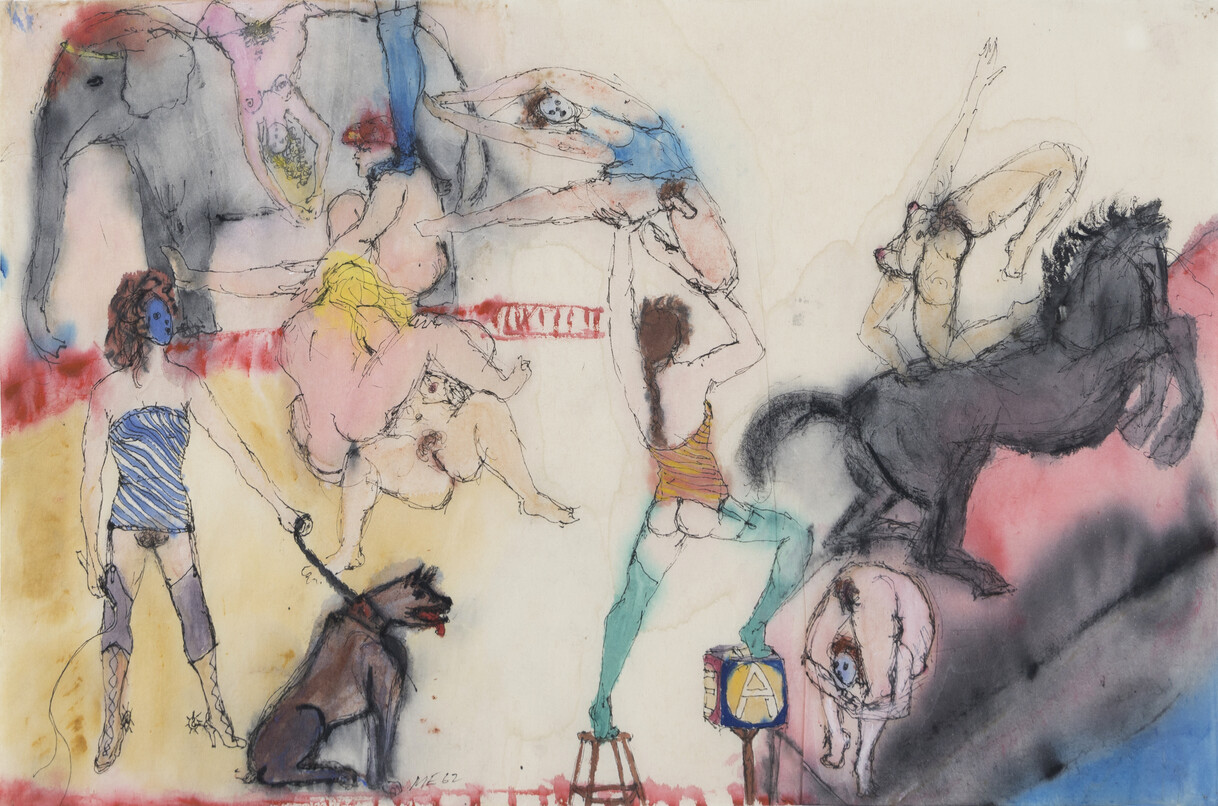

In 1962 both of these galleries closed and Edelheit found herself in a transitional stage. In the months following these closures, she began to study the human figure, a decision that was both inspired by her disinterest in abstraction and a formative tour of France, Italy, Greece and Turkey after her 1961 exhibition at the Judson Gallery.6 She created a number of erotic watercolours FIG. 1, depicting sexualised circus performers engaged in suggestive acts of dominance and submission, as well as a series of doll-like figures. Perhaps the best-known example of such a watercolour is Mr America’s Cut Out Dream FIG. 2, which depicts a male nude in the centre with small circular voids in his limbs, indicating the pin-hole joins of a paper doll. He is surrounded by a varied assortment of clothing items and body parts, including breasts, a whip, make-up and wigs. In her study of the erotic in Edelheit’s work, the art historian Rachel Middleman has noted that such examples serve as an early indication of the artist’s proclivity to ‘claim these sexual fantasies as subject matter for art […] at the height of social struggle between sexual liberalism and middle-class values that inhibited the public display of sexuality, let alone its deviant forms’.7

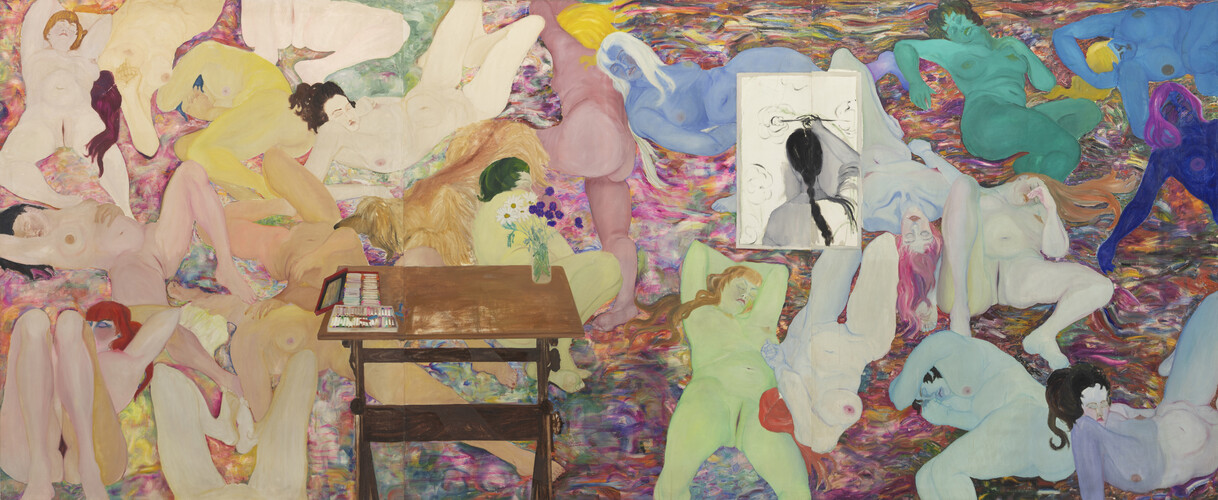

Edelheit was bold in her visual evocation and celebration of non-normative sexual acts and gender non-conformity. In 1963 she began creating the large-scale Flesh Walls, of which she produced four in total, the last completed in 1966. For this series of paintings, Edelheit worked individually with live models in her rented studio in New York’s Hotel Wales; the models were both male and female, almost all of whom were high-school students and either the children of her friends or of associates of her husband, Henry Edelheit, a psychoanalyst.8 Although the paintings depict large groups of nudes in various combinations, Edelheit composed each Flesh Wall from an assortment of individual studies; the only exception being Flesh Wall with Table. Through this collage-like process, Edelheit treated the models’ unique qualities – their form, position and rendering – as individual puzzle pieces. She also introduced elements of creative fantasy that align with a queer utopian imagining of an ideal future that exists separately to heteronormative society and its tenets – a type of ‘dreaming’ that may never be realised and that remains in a realm of potentiality, not one grounded in reality. This aspect is heightened in Flesh Wall with Table, which, in a recent interview, the artist described as the only ‘Flesh Wall’ painting created without models – a stretch of ‘invented bodies’ crafted entirely from Edelheit’s imagination.9

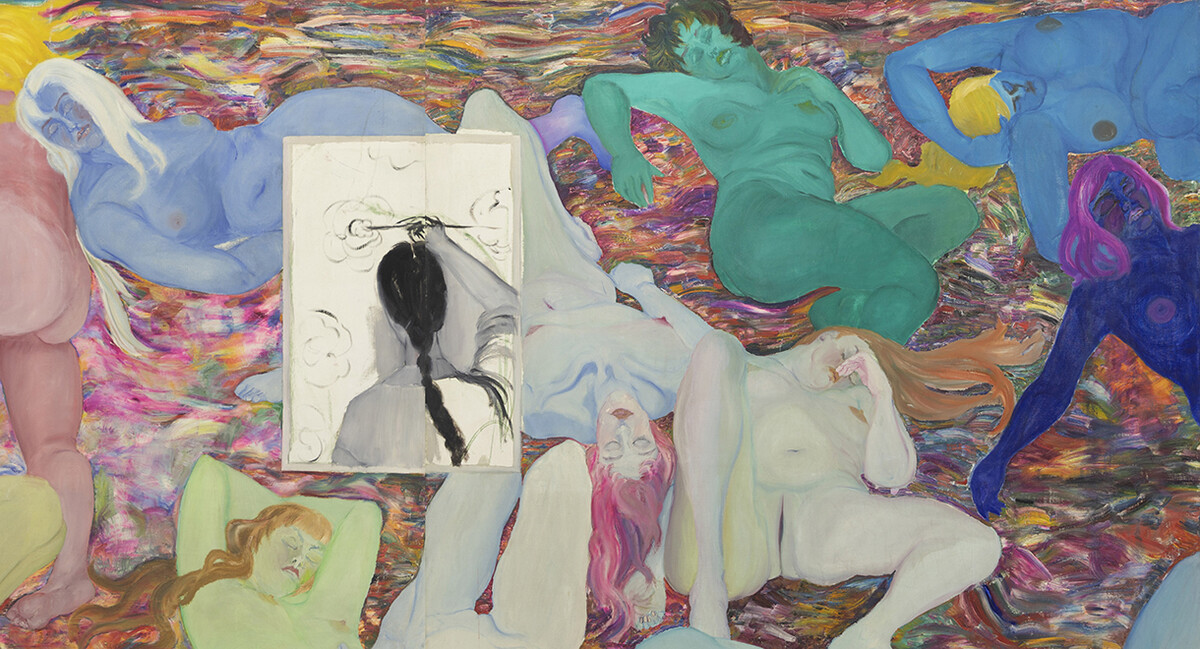

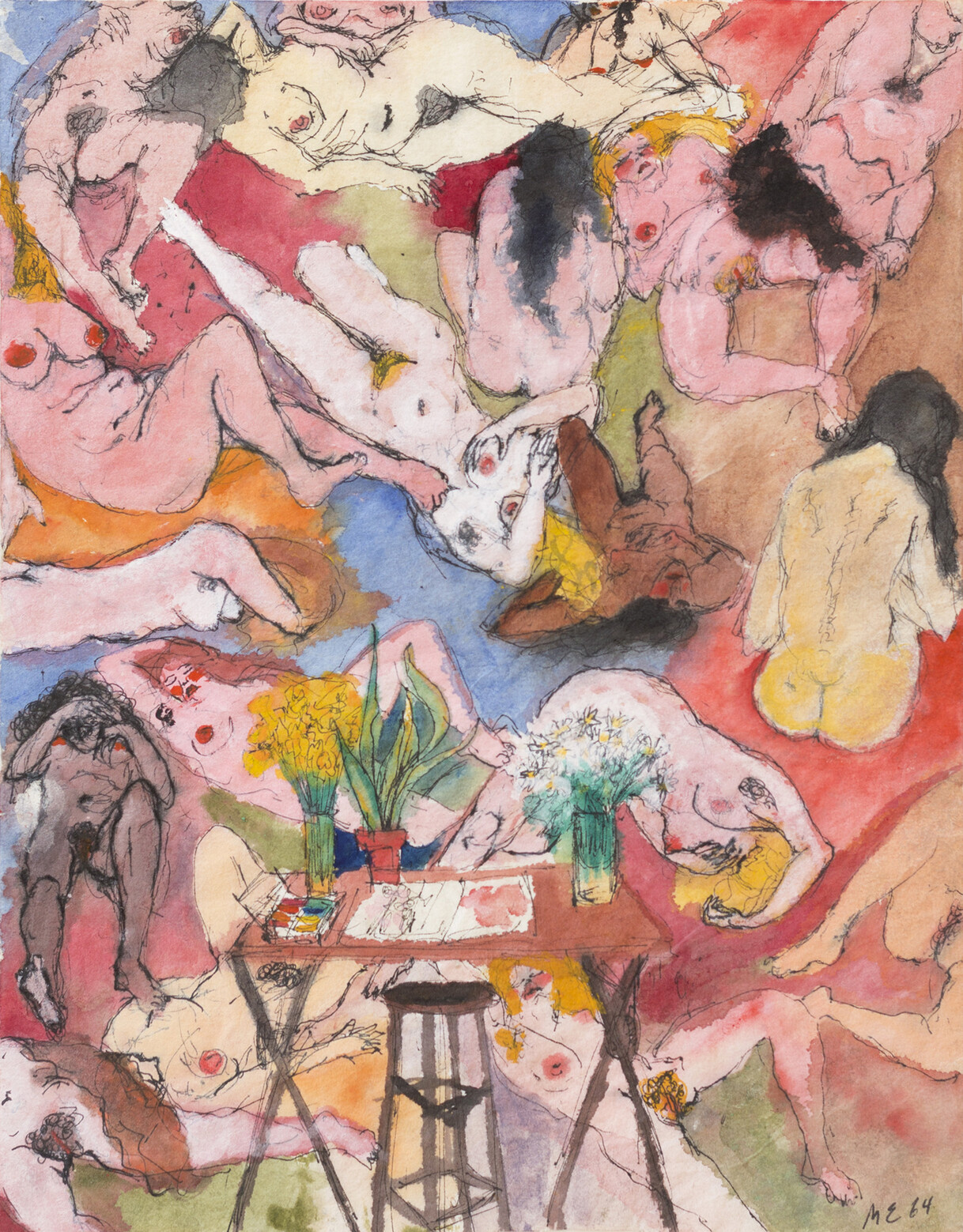

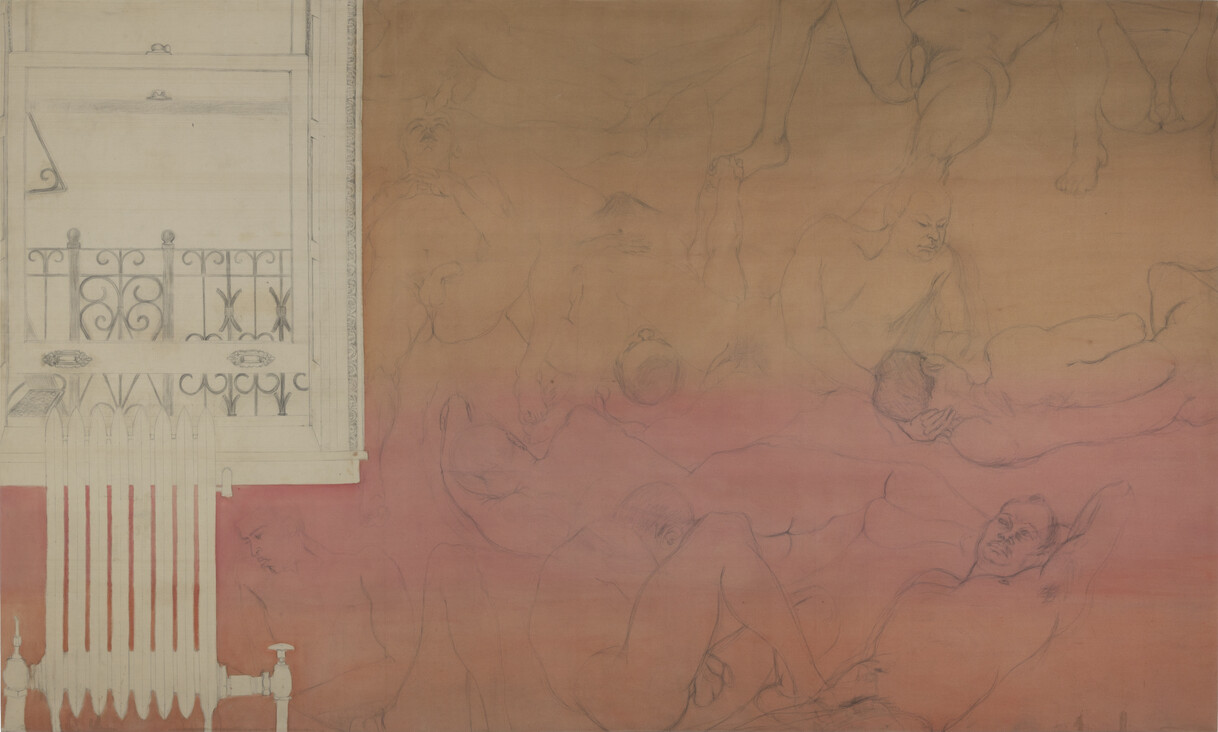

Study for Flesh Wall (Flesh Wall with Drawing Board) FIG. 3 and Flesh Wall with Table FIG. 4 both depict women leisurely lounging together in the nude. The women Edelheit paints are a variety of shapes and sizes, have varying degrees of body hair and a range of skin colours. In Study for Flesh Wall, Edelheit paints complexions in shades of pink, yellow and brown, whereas in Flesh Wall with Table, the hues used strike a more utopian note, resembling a colour spectrum that graduates from peachy pinks and yellows to greens, teals and royal blues. The reclining women use one another’s bodies as supports and as places of rest and safety – their level of comfort and ease made apparent by the fact that they appear to be sleeping on one another. Some cover their faces entirely, while others allow the hands and heads of others to rest on intimate areas, including their throats, breasts and buttocks. Collectively, they form a communal care network.

Edelheit embeds herself in the final work using a rectangular mirror, in which we see the artist, rendered in black-and-white, painting a floral pattern. This detail echoes Edelheit’s 1963 self-portrait, Tattooing with Rose Wallpaper FIG. 5, in which she inserts herself in a room decorated with yellow and white floral wallpaper in the reflection of a mirror. In the foreground of Flesh Wall with Table, Edelheit has painted a table, on which rests a set of oil crayons and a vase with flowers. These elements introduce a sense of the quotidian and routine. The physical location of this network of bodies remains ambiguous in both the study and painting, their resting place solely identified by a background composed of lush strokes of vivid, intermingling colour.

These multi-panel paintings suggest non-normative ways of visualising experiences of intimacy and raise the question of women’s objectification in more conventional erotic art being made in the United States at the time, such as that of Tom Wesselmann (1931–2004) and Tomi Ungerer (1931–2019).10 Both Wesselman’s and Ungerer’s work, in different ways, arguably render the female body as nothing more than a sexual object and machine. Although Edelheit’s Flesh Wall paintings are certainly erotic, they do not align with Lucy R. Lippard’s criticism, posed in 1967, of the ‘unprurient peep [shows]’ of erotic art dominated by the male gaze and overly sexualised renderings of female bodies, which the writer found gratuitous and far less titillating than more abstracted eroticism.11 Instead, Edelheit depicts the female form from her own perspective and identity as a cisgender woman. This unites her work with that of other women artists of the 1960s, such as Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019), Anita Steckel (1930–2012) and Marjorie Strider (1931–2014), who also subverted the male gaze and its objectification through their representations of the erotic.12 As Middleman argues:

Artists who were identified as heterosexual women contributed to [the destabilisation of heterosexuality], not by rejecting heterosexuality entirely, but by creating art that challenged heteronormative, binary notions of sexuality, which had long served as the underlying assumptions for both art history and art criticism.13

For Edelheit, it has been essential to retain the authenticity of the people she rendered in her work – a detail that separates her from the majority of her male counterparts at the time:

If I worked with bodies, I very consciously wanted them to look like real people [. . .] I didn’t want to idealise them. I did not think of it as destabilizing, but I did think about it as challenging the traditional imagery of women by male artists, which was often objectifying. I had spent a lot of time looking at this stuff, and I was very aware that this was not what I wanted to do.14

Edelheit’s approach denies voyeurism, finding it, as the feminist film scholar Mary Ann Doane notes in her writing on the female gaze, ‘extremely difficult, if not impossible, to assume the position of fetishist’.15 Rather, her closeness to the image as both woman and maker introduces a narcissistic desire, which collapses the distance between subject and object.16 This proximity denies the male gaze room to penetrate Edelheit’s intimate web of female nudes, thus introducing a utopian mode of viewing beyond reality. Her subjective female gaze frees her nudes from the fetishistic male gaze, allowing it to exist within an all-female, utopian space.

Edelheit’s act of looking is, the present author argues, inherently queer. In their writing on queer viewing, the scholars Caroline Evans and Lorraine Gamman examine the art historian Kobena Mercer’s ‘idea of multiple and simultaneous identification’ arguing that it has always been ‘part of the female experience of viewing’.17 Evans and Gamman suggest a ‘queerer’ and more expansive range of a spectator’s possible identifications with and of visual information. Within this theoretical framework, Edelheit’s gaze has the potential to be simultaneously female and queer.18 This multiplicity, in turn, grants her viewers the possibility of accessing her work in an equally fluid manner. Equipped with such freedom, Edelheit’s Flesh Wall with Table becomes a material articulation of Sedgwick’s idea of queerness as an ‘open mesh of possibilities’ and, as a result, can be considered in the growing gay and lesbian communal movement of the 1960s and 1970s.19

The contradictions of communal living

Edelheit’s inclusion of her mirror-presence in Flesh Wall with Table addresses the juxtaposition between the ‘utopian’ environment that queer communal living sought to create – an ideal, free space that existed outside of societal norms and expectations – and its ‘dystopian’ tendencies and realities, such as internal discord, misunderstanding and conflict, which kept their dreams of utopia at a distance. In his essay ‘Of other spaces: utopias and heterotopias’, Michel Foucault posits the mirror as existing in between utopias and heterotopias, the latter of which he defines as ‘outside of all places even though it may be possible to indicate their location in reality’.20 He writes:

I believe that between utopias and these [. . .] heterotopias, there might be a sort of mixed, joint experience, which would be the mirror. The mirror is, after all, a utopia, since it is a placeless place. In the mirror, I see myself where I am not, in an unreal, virtual space [. . .] But it is also a heterotopia in so far as the mirror really does exist in reality.21

Whereas Edelheit’s study arguably exists within a heterotopia – locatable due to its recognisable human forms, despite them occupying a space far beyond the traditional norms of 1960s society and situated in ambiguous terrain – Flesh Wall with Table is permeated by utopian anticipation.

By inserting herself into the work through a mirror, Edelheit imagines herself within the utopia she depicts, a place that is ‘fundamentally unreal’.22 However, she also distances herself from it, as the mirror locates her in the actual space she occupies in her lived experience. This separation is heightened by the depiction of her body in black-and-white, a stark contrast to the vivid colour of the rest of the work. By creating this simultaneous connection and detachment, the mirror and its reflective properties serve as a means through which Edelheit acknowledges her role as the creator of such a queer utopian landscape alongside the impossibility of her ever joining it. She imagines this future for others but not herself. This representation – of being both there and not fully there – resonates strongly with the queer theorist Jose Esteban Muñoz’s positioning of queerness as ‘not yet here’ and as ‘an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world’.23

Although the idea of communal living was certainly not a new one – in colonial America, rural life has involved communal living in various manifestations since the seventeenth century – a communal revival took place in the mid-1960s and remained popular until the mid-1970s.24 The reappearance of communes at this time came out of the civil rights, women’s rights, gay rights and anti-war movements that defined this historical moment. Within this sociopolitical context, communal living became a form of escape from and resistance to heteronormative society, and a move towards a utopian future existing ‘outside of space and time’.25 As the art historian Jo Applin has written, the concept of utopia – defined here as an imagined place beyond reality – is a recurring and ‘powerful trope [. . .] for radical politics’, which already engaged ‘complex world-building processes that involve thinking alternatives to the world we already inhabit’.26 The numerous communes that developed embodied a championing of the group instead of the nuclear family unit, which had come under attack at a moment of countercultural upheaval that saw the rupture of traditional standards.

The sociologist J. Milton Yinger coined the term ‘contraculture’ in 1960 to refer to a group whose principles are ‘specifically contradictions of the values of the dominant culture’.27 The American academic Theodore Roszak subsequently situated counterculture between and among both political and cultural spheres, thereby introducing personal transformation as a vital element for revolution.28 Roszak’s theoretical approach was unusual amid a wave of critics and observers who separated counterculture from any political or activist charge.29 Yet, the 1960s American counterculture was deeply political; it was only that its methods of expressing radical activism were not seen as such at the time. Communal escape, for example, was relegated to apolitical categorisations despite its clear associations with aims of the New Left, which was acknowledged as a political movement.30 The difficulty lies in identifying the difference between hippy and leftist thought regarding how to best incite social change.31

For the countercultural youth, creating such transformation was deeply personal and involved a sharp break with the conventional societal values that no longer provided safety and comfort but rather constricted, unsettled and disarmed. Widespread and excessive use of psychedelic drugs was a part of the counterculture – a detail Edelheit may nod towards with her eccentric choice of colour palette and decision to create a background of swirling hues in Flesh Wall with Table. Such methods of resistance demonstrate the deep influence of the countercultural icon Timothy Leary (1920–96), whose famous cry for young people to ‘turn on, tune in, drop out’ during San Francisco’s 1967 ‘Human Be-In’ – a gathering of over twenty thousand hippies in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco – helped usher in the Summer of Love.32 Leary’s words kindled a culture that communally dropped out of traditional society as a means of resistance and creating a new life for themselves. Edelheit may allude to this in her decision to depict the women in Flesh Wall with Table asleep. However, the realities of 1960s dropout culture existed in opposition to its idealistic aims: although these young people did manage to evade unwanted societal pressures and expectations, the ways in which they did so were temporary solutions that ultimately left them with both old and new challenges.

The countercultural practice of dropping out as a refusal to conform to normative societal values parallels the decision of gay and lesbian individuals to communally come out of the closet in the 1960s and 1970s as a rejection of the expectations of a heteronormative world. As the queer theorist Robert McRuer notes, gay collectives abandoned ‘the same “straight” society that various facets of the counterculture had been critiquing and rejecting throughout the 1960s’.33 Both movements strove to break with this hegemonic heterosexual society and to redefine their reality through communal escape. McRuer states that ‘the burgeoning gay movement made possible the formation of new identities individual and collective, and because of this, communal living could indeed be seen as a natural part of some people’s coming out process’.34 Gay and lesbian communes gave individuals a sense of belonging and allowed them to discover and celebrate themselves in a safe space. They served as a welcome alternative to the traditional and heterosexual notion of the nuclear family, thereby affording their members the opportunity to collectively build towards a queer utopia existing far beyond the realities of conventional society.

However, while queer communal attempts redefined the meanings of family and home, as with the strategy of dropping out, so the realities and practicalities of these arrangements were inevitably at odds with their utopian ideals. Communes, regardless of their structure, presented many challenges to their members. For example, different approaches to cleanliness, communication and boundaries meant that tensions inevitably arose and required negotiation that left one or more parties unsatisfied.35 Navigating these differences required constant communication and a frequent reconsideration of rules, which developed into a new activist approach, complete with its own politics, principles and order. To address surfacing tensions and avoid festering frustrations, the lesbian separatist communards of WomanShare in Oregon, for example, always made time to discuss any personal or collective issues.36 However, the unique intimacy involved in queer communal living introduced challenges that frequent conversation often could not resolve.

In Country Lesbians: The Story of the WomanShare Collective, the members of the collective reveal the complexities of their relationships within the commune. Between sleeping with one another, being intimate with many others and also loving one another as friends, WomanShare involved a delicate balance of constant (re)negotiation and continued redefinition of individual and group dynamics. In the book, a member named Dian, shares:

I am coupled with Sue, but I’m also closely involved with the three other women I live with. Carol and I are long-time friends [. . .] twelve years we’ve known each other. Billie, I’ve lived with the last three years, and Nelly and I now share a special kind of intimacy when we interpret our dreams together’.37

Sue’s account of this moment in her life reveals the difficulty underlying such intricate relationships:

When Dian and I began our relationship Dian was also lovers with Nelly. So jealousy and possessiveness were there to deal with from the start […] At first, I tried to subdue my jealous feelings. But my jealousy of Nelly seemed to grow in direct proportion with the growth of my love for Dian [. . .] I didn’t like wondering every night who Dian was going to sleep with.38

Although conversation and negotiation were methods of dissolving such tensions, there were no solutions for these emotional challenges, as they were deeply personal and involved each person relinquishing some element of comfort in order to achieve the highest level of satisfaction for the group as a whole. The inability to resolve these strains reveals the dystopian side of queer communal living: no matter how much the members of WomanShare attempted to evade the tensions of communality and create a lesbian separatist utopia, this goal would always remain, as Muñoz posits in his writing on queer futurity, ‘an ideality’ on the horizon.39

‘Flesh Walls’: gesturing towards collectivity

Despite inevitable quarrels and friction, acts of care, trust and cooperation, which define all forms of communal living, represent the tangible ways in which communards strove to create a utopian space that entirely satisfied all members and transcended conflict. Edelheit’s Flesh Wall with Table embodies these communal care networks. The women in the painting are buttressed, sustained and comforted by one another, all of which are actions that require a great amount of trust, which is only amplified by their nude state. Some are asleep, some rest their feet and hands on other women’s chests or hips, some hold their own breasts. Although these acts certainly have the potential to be sexualised, Edelheit refused to do so, thereby allowing this tender web of relaxed bodies to exude an overwhelming sense of calm and routine – one that mirrors everyday communal life.40 Edelheit’s inclusion of such commonplace objects as the table and vase in the work further normalises what we see.

It is also significant that Edelheit’s Flesh Wall paintings grew out of the work she was producing immediately before – a series focused on floral wallpaper, including Tattooing with Rose Wallpaper. Edelheit remembers being fascinated by wallpaper and, especially, by the fact that people used it in their homes. In wondering what would come after her wallpaper works, Edelheit thought, ‘Why can’t I make bodies into wallpaper?’.41 She was additionally inspired by a line uttered by the American comedian W.C. Fields in the film Mississippi (1935): ‘I unsheathed my Bowie knife and cut a path through this wall of human flesh, dragging my canoe behind me’. Edelheit set out to create her own ‘wall of human flesh’, using the motif of floral wallpaper as a base. This aspect is noteworthy as it demonstrates that a common decorative component of domestic spaces served as a key element in Edelheit’s creative process and furthers the sense of the quotidian embedded in the various details she chooses to insert throughout the work.

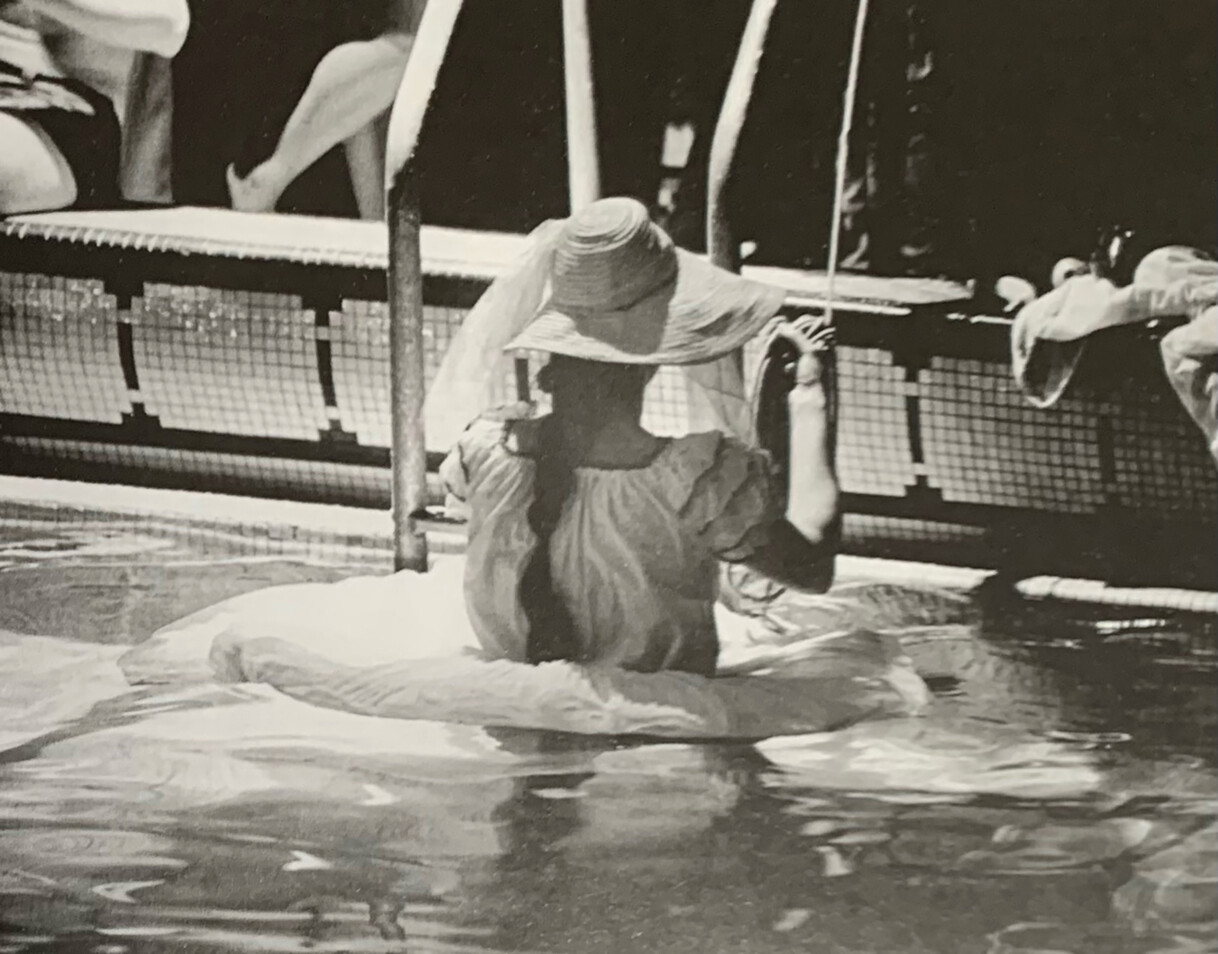

This aspect of Flesh Wall with Table recalls Edelheit’s participation in an experimental art performance of the same year. Along with the artist members of the Reuben Gallery, Edelheit challenged traditional notions of artmaking through the creation of experimental, mixed media objects and Happenings. In 1965 Edelheit took part in Oldenburg’s important performance Washes FIG. 6 at Al Roon’s Health Club, New York – notoriously frequented by celebrities, artists and counterculturalists, including, most notably, Andy Warhol.42

For this Happening, Edelheit and three other women entered the health club swimming pool fully clothed. After submerging themselves in water, they undressed and hung their wet clothing on a clothesline suspended above them, running across the length of the pool. Edelheit and her fellow performers then proceeded to use brushes and sponges to wash each other’s bodies, whistling throughout as one might casually whistle while doing housework. These simple acts recall the familiarity, comfort and ease that permeate communal living spaces. The performers’ lack of self-consciousness around one another, both generally and while nude, and their collective engagement in mundane chores, such as hanging clothes to try and acts of care, including bathing one another, directly evoke the tranquil communal environment Edelheit depicts in Flesh Wall with Table. Washes also introduces a sense of playful and flirtatious provocation through the participants’ disrobing and sensual physical contact, which mirrors the intersection of both erotic and platonic intimacies and the everyday in women-only communal spaces that Edelheit manifests in her painting.

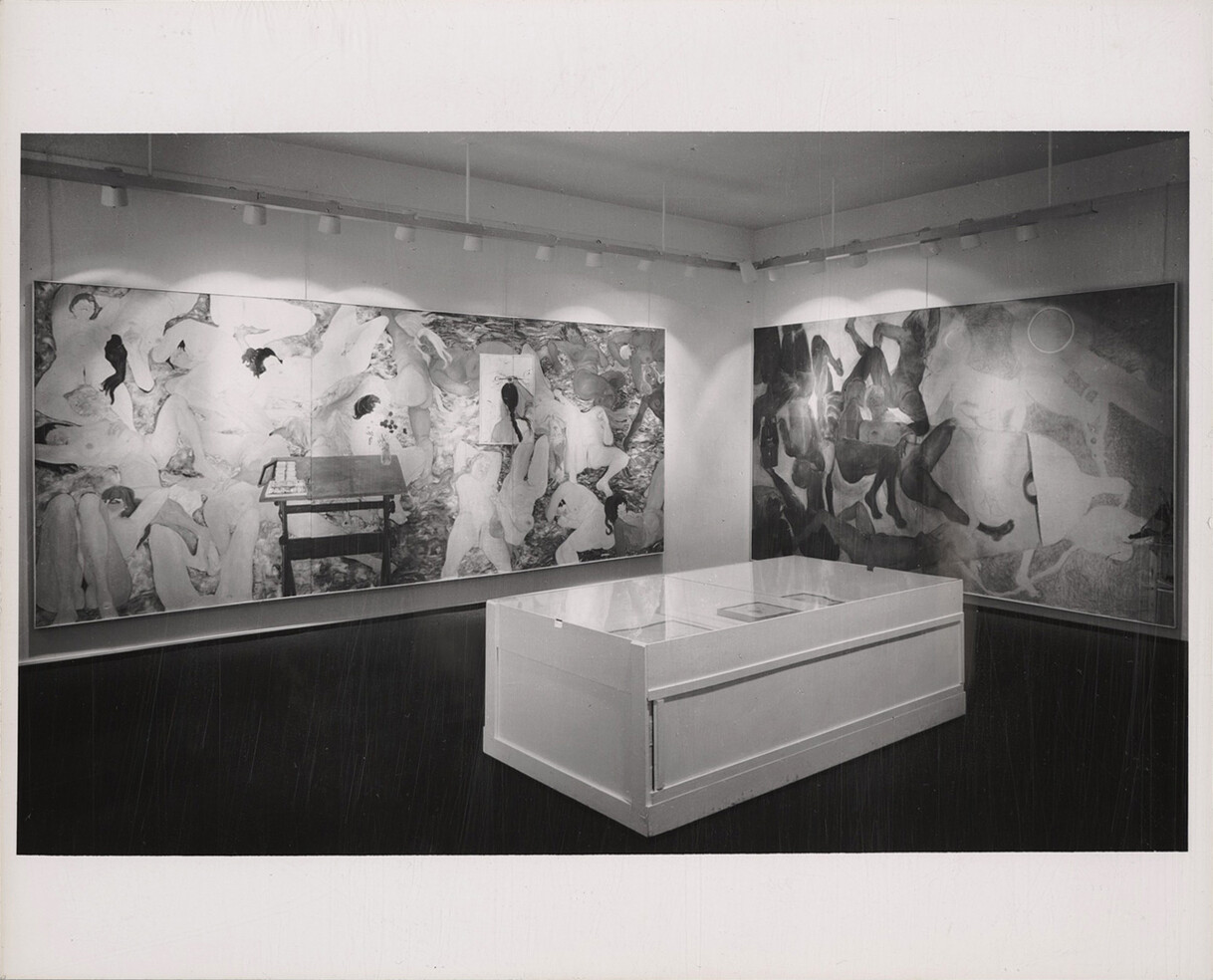

In its radical depiction of queer interdependency and its massive scale, Edelheit’s Flesh Wall with Table gestures towards the utopian future queer communards sought to collectively summon through their tender care networks. In 1966 Edelheit was invited to present a solo show at Byron Gallery, New York FIG. 7, in which her four Flesh Wall paintings were exhibited, including Flesh Wall with Table as well as Flesh Wall with Ladder FIG. 8 and Flesh Wall with Window FIG. 9.43 By choosing to display this particular body of work – comprising paintings made within a year of each other – together at this moment in time, the exhibition revealed the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with themes of collectivity and domesticity during the mid-1960s, which more broadly reflects an interest in and awareness of the growing queer communal movement at this time as well as the trends that defined its development.

In its early beginnings, queer communal living involved either lesbian women or gay men. This would not change until the late 1960s and early 1970s, when communes such as Lavender Hill near Ithaca, New York, formed. The Lavender Hill communards were committed to creating a multi-gender space that invited lesbians and gay men to live together as a means of collectively challenging the gender norms that were perpetuated within and among the queer community at the time.44 During the mid-1960s Edelheit typically kept the protagonists in her paintings separated by sex – a decision that mirrors the tendency towards gender division in early experiments with queer communal living.45 Her Flesh Wall with Table and Flesh Wall with Window, for example, include large groupings of women and men, respectively.

Flesh Wall with Window is markedly different from Flesh Wall with Table, its background subdued in colour and its male figures mere sketches compared to the fleshy, candy-coloured women in the latter. Flesh Wall with Ladder, conversely, is unusual as it depicts a mixed group. Unlike Flesh Wall with Window and Flesh Wall with Table, Flesh Wall with Ladder looks toward a nearing future that would involve a more expanded sense of what queer communal living arrangements could look like. Edelheit’s Flesh Wall paintings commanded the Byron Gallery space, creating an entirely immersive environment. Their size enabled the nude figures depicted in the work to be essentially at human scale, which suggests that both the viewer and Edelheit’s representative beings occupy the same plane. With the gallery walls almost totally occupied by these multi-panel works, its space was transformed into an engrossing landscape, which transported viewers to an unknown place within an alternative future. The curatorial decision to display Edelheit’s Flesh Walls in the gallery in this way – of course driven foremost by the work’s needs – therefore evokes a utopian ‘non-place’, which exists far beyond spatial and temporal confines.46 By immortalising her dreamlike landscape on canvas, Edelheit’s fantastical vision can always exist within this utopian sphere unlike the queer communes of the 1960s and 1970s, which would remain within a dystopian realm rooted in reality.

Dreaming utopian futures, then and now

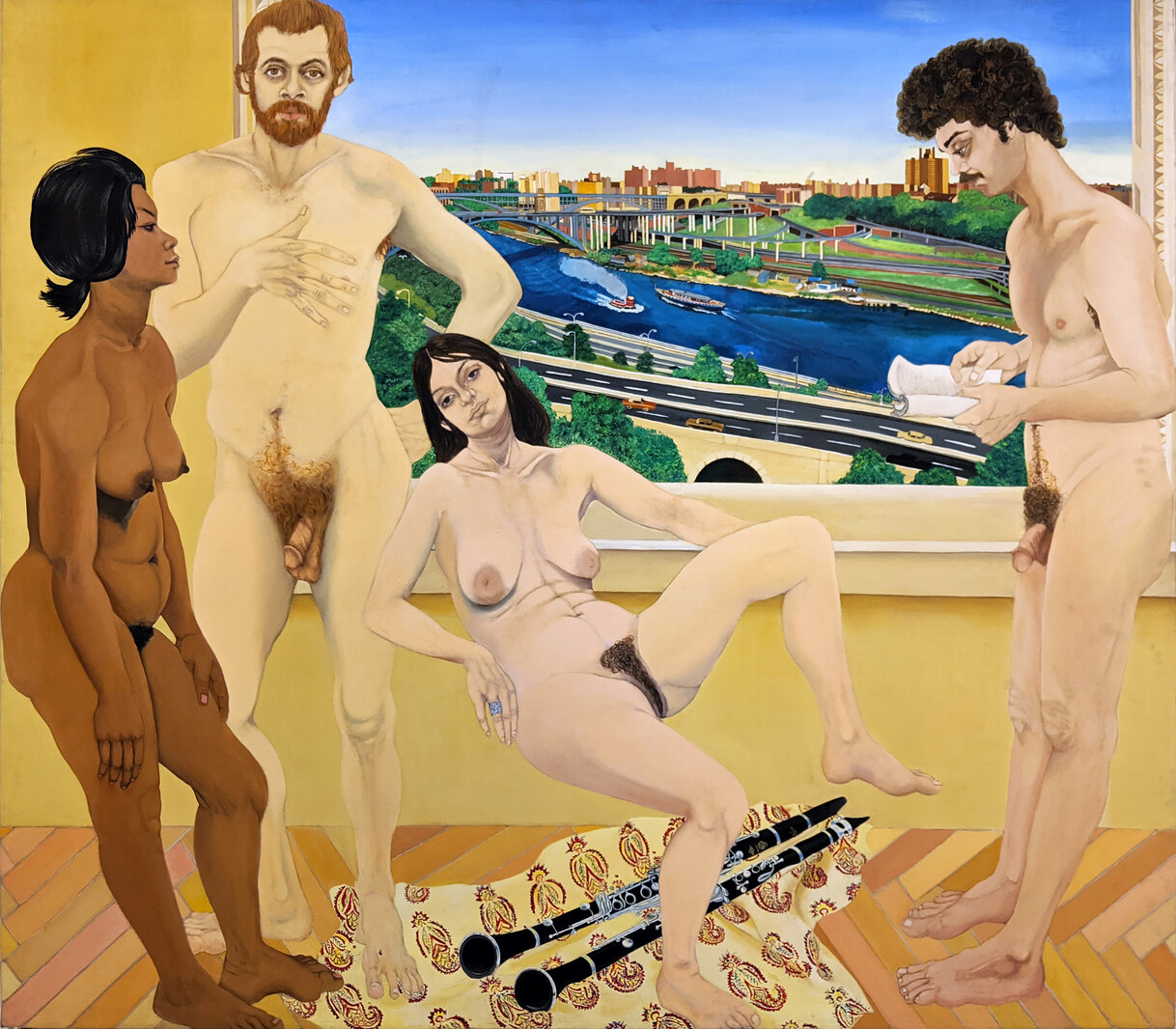

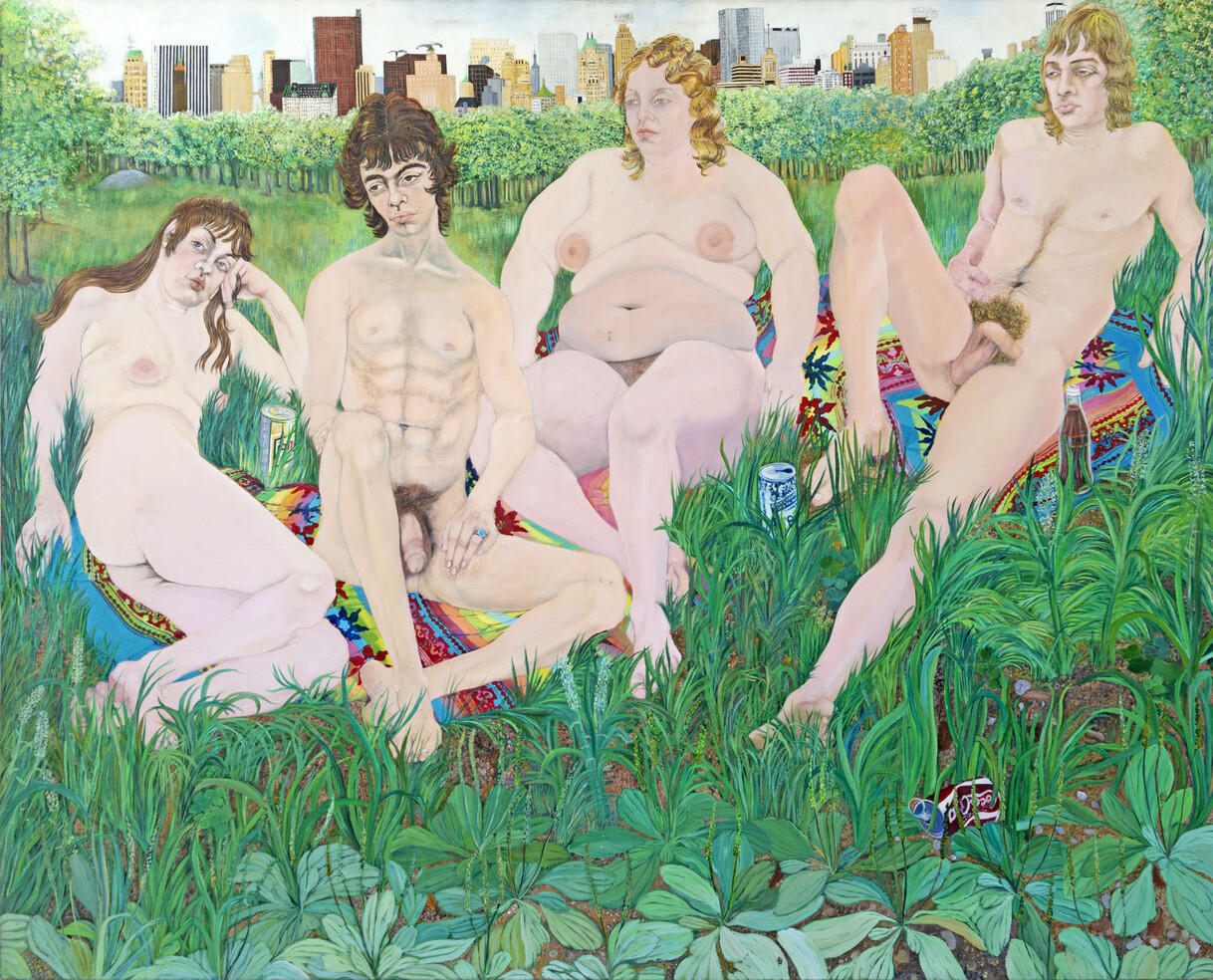

By 1968 Edelheit had extended her large-scale paintings to include life-size nudes. Works such as View of Cross Bronx Expressway From Highbridge Park FIG. 10, which depicts four naked figures – two male, two female – continue to probe the inquiries Edelheit initiated with her Flesh Walls. While more intricate in detail, these nudes are equally as realistic and unidealised as the figures Edelheit painted in previous works, replete with stomach rolls, sagging breasts, body hair and flaccid penises. Like in Flesh Wall with Table, a type of surreal fantasy permeates the painting: Edelheit depicts one figure in the work lying back, however, without much to realistically support their body in that position, they appear to be floating in space. Edelheit chooses to include various skintone and, again, adds details that allude to the quotidian. One figure reads a book; there are two clarinets on a rug; and the scene supposedly takes place within a domestic interior based on the window that looks out onto New York’s Cross Bronx Expressway. Like the subjects in Flesh Wall with Table, these figures appear to be tuned out, but in a more explicit way – staring blankly into space (or into the pages of a novel) and seemingly out of touch with reality.

In View of Cross Bronx Expressway From Highbridge Park, Edelheit again reverses and disrupts the traditional roles of male artist and female model. She alludes to the countercultural movement by depicting four youths who could be cohabitating after choosing to ‘drop out’ of society, envisioning the simultaneous potential for both (homo)erotic desire and platonic kinship. In the context of the early 1970s, this painting recalls the ways in which young people attempted to harmoniously unite the erotic and platonic within domestic spaces through communal living experiments. By using the window to visually separate the pleasure, rest and ease that she depicts in the domestic interior as well as the hustle and bustle of the Cross Bronx Expressway, Edelheit suggests a disconnect between the hopes and dreams of the countercultural movement and reality.

Similar works, including View of Empire State Building from Sheep Meadow FIG. 11, indicate an ongoing interest in such themes; from the 1960s Sheep Meadow became an iconic gathering spot for New York’s counterculture.47 Edelheit’s more frequent union of male and female figures in her paintings during the early 1970s is also worthy of note, again in light of the history of queer communal gathering. Her visual gesturing towards queer commune-building and its promise is rooted in the historical context of the 1960s and its countercultural movement but also manifests a visionary depiction of utopian queer futurity. Edelheit’s Flesh Wall with Table engages with the historical beginnings of this revolutionary action taking and world-building; in doing so, it continues to inspire in an era where we proceed to strive towards a utopian future.

Acknowledgments

This article would not have been possible without the support of a number of individuals, whom the author would like to acknowledge. First and foremost, Martha Edelheit, for her generosity, her willingness to share her perspective and, of course, her work. The author would also like to thank the team at Eric Firestone Gallery for their support, in particular Jennifer Samet and Kate Moger. Lastly, the author would like to thank Jo Applin for her continued belief, her teaching, encouragement and comments, which have deeply impacted my work and thinking.